The starting point

All my work stems from the same place inside myself. The need to show proof of life, to give a voice to that which appears and disappears, to the ones pushed aside, to the forgotten ones: people, emotions, stories or feelings in the body. I embrace emotions and find inspiration in feeling them deeply. I draw a lot from my inner world and what I experience in my life and in my body. My environment and my body are usually my starting point.

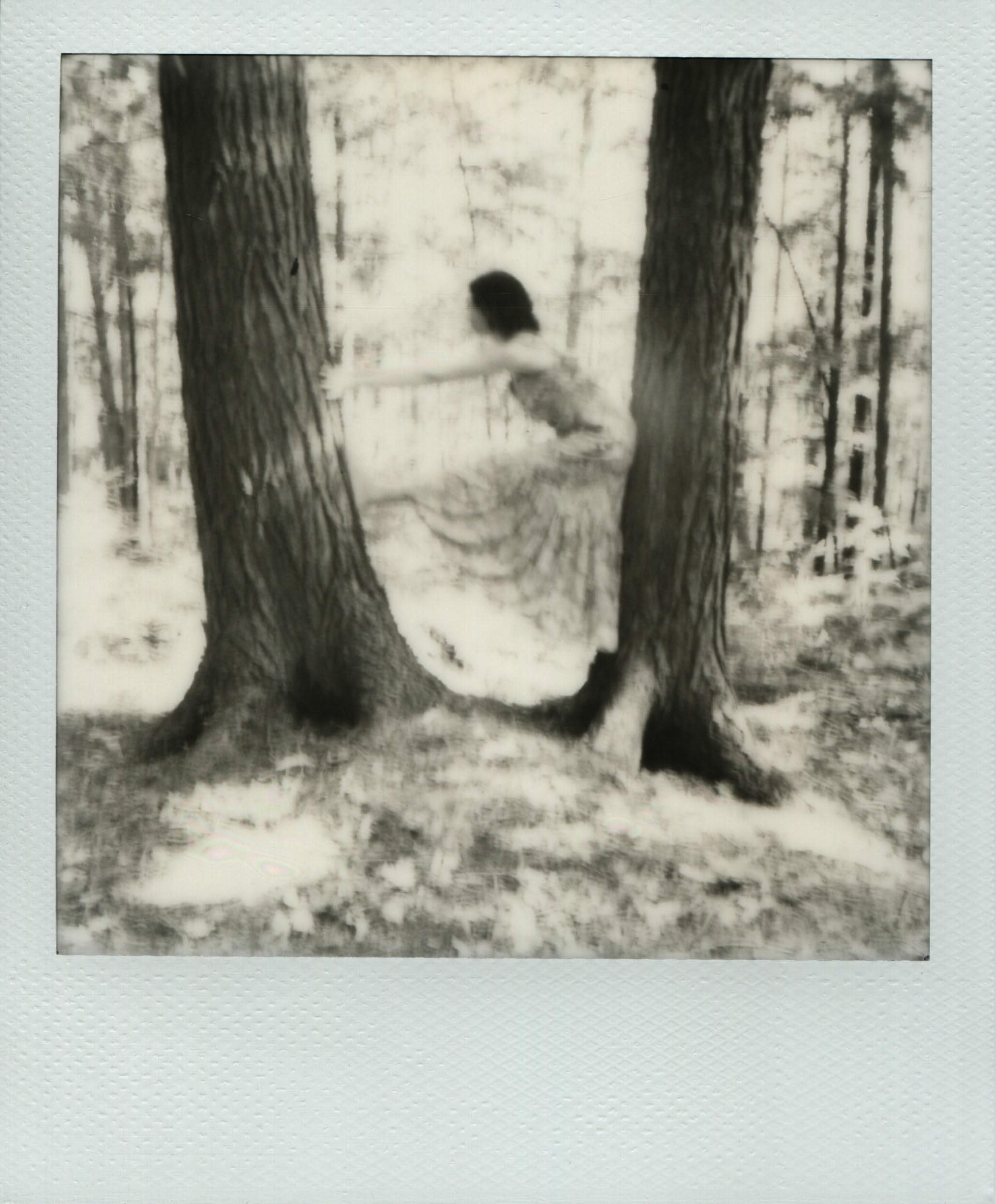

Both these images were created in 2019 as a part of Alix Van Der Donckt-Ferrand’s and my show in Toronto at a gallery named The Loon. The show was called Wildfire, and was our response to what we felt we were supposed to be in the art world, coming out of school. Responding to the stereotyping and the anger we felt towards female stereotypes in art.

A child of the Americas

I was born in Bogotá in the mid-1990s. The situation in Colombia was complicated, to an extreme. I’ve always associated Colombia with a rollercoaster. So much violence and pain, but so much beauty, so much serendipity, warmth, humility. It’s difficult to talk about it. But Colombians have a great sense of humour.

I moved to Canada in May of 2001. I emigrated on my own when I was 6 years old. My mom had travelled to Toronto for 8 months to learn English when I was 5, and ended up getting married there. My father wouldn’t let my brother move with us, and since my mom was already there, I had to go on my own. I was excited to be with my mom again, as it was very painful for me to be separated from her so young and for so long. I completely blocked out any fear I had about moving there. I always carried a backpack with pencil crayons and a sketchbook and this little pillow from when I was born. I remember flying on my own for the first time, and I had a hole in my special pillow. The older woman sitting beside me helped me sew it back together. This was a few months before 9-11 when you could still bring a sewing kit on the plane with you.

For the next year I would live like an only child in Toronto with my mom and her new husband (who I really liked.) He had a clothing store and we stayed on the top floor of the building where he had a warehouse. The only other people living there were artists. Designers, musicians, painters. I would ride my scooter in the old chocolate factory hallways, irritating some of the tenants with the sound of the gum wheels rolling down the creaky, thin wooden floors. I was the only kid living in the building. I remember one neighbour, an architect/artist, making me a wooden sandbox outside our apartment window on the roof. It pleased me to see people doing what they love to do.

Being surrounded by so many artists in this new city, alone with my mom and her new partner, was very exciting. I began obsessively carrying around a small, plastic see-through briefcase with paper and pencils everywhere we went… I was always drawing, ever since I can remember.

I was obsessed with colour and there was something very comforting to me about colour.

I made my first friend with the son of two friends of my mom’s partner. His name was Chilin. His parents were from Venezuela. Chilin was my age and diagnosed at 11 months with a Wilms tumour. We would visit him as often as we could at the Hospital for Sick Kids and Ronald McDonald House, where they stayed when he had treatments in Toronto. I played with the kids that lived there. Painting one day in the hallway with several kids, I asked one girl to pass me the blue paint, but she was blind. I will never forget trying to explain to her what the colour blue looked like, what it felt like, why it was my favourite colour. I couldn’t fathom the concept of blindness. And it terrified me. I asked my mom over and over, “so she really doesn’t know what blue looks like?”

I was obsessed with colour and there was something very comforting to me about colour. It’s hard to explain even now, but there’s a sense of embrace I feel when I see or use colour. I try to communicate through colour — it’s the most direct way to explain my feelings. I’ve dreamed of being an artist my whole life. It has always been my obsession.

I enrolled at OCAD University (Ontario College of Art and Design University) in 2014, where I studied under the program “Integrated Media” for 5 years. I tried to use the university as a laboratory experiment. I was very serious about school while I was there.

Yet no matter how serious I was, there was a disparity happening inside of me while in school. I felt worlds apart from most of the kids in my program for many reasons, one being that I had been waiting 13 years to get there, while they mostly didn’t seem that interested in being there at all. I would come home to my apartment in Regent Park (historically a low-income neighbourhood in downtown Toronto) and feel very dislocated and existential about my life. I was 19 years old, family-less, and deeply devoted to my vocation. But all around me was homelessness, poverty, a gap between my daily life of being an art student and the reality of my environment. I asked myself constantly, what does this mean? I felt like I was somehow posing as an art student when my reality was much closer to the bone than that.

I began going every Sunday to Allan Gardens, which is a historical park downtown, known for its botanical garden but also as the site of many political protests. I went there almost every Sunday for five years. It was my way of connecting with my world, making a new family, feeling seen without having to say a word.

I had my first solo/public installation when I was 23 at Allan Gardens. It was such a special moment for our community. Bringing the invisible to the forefront, confronting the neighbourhood with those whom they tried to disregard. It was called “Guardians,” an ode to the Indigenous homeless men who took physical and spiritual care of the park. It had a huge impact on us. It felt like a win for the community — which the art world took no notice of. I thought it would have a repercussive impact in the city or the club that I wanted to be a part of, but it fell to the margins. To me, this was such an important and special work for the history of the city and my Toronto family.

I always carried a lot of resistance to academic “heavy” artwork. I felt that if something was good, there should be a visceral response in the body. The summer before starting my thesis, I took my first trip to Europe where I was hoping I would find inspiration for my final university work. It was Europe! How could I not come back inspired? But nothing struck me at all. I knew I wanted something that people like me could connect to without reading anything.

The day before school started, I went to the beach. There was a woman swimming in the lake who seemed to be having a tantrum. I was consumed by her evocative, dancerly body movements. The way her hair whipped the water, how she yelled at the lifeguard who was trying to tell her to leave, how free she was, how openly angry she was. I couldn’t stop watching her. Her performance was exemplary. I got goosebumps all over my body, and I knew that this was a subject I needed to explore.

Getting in touch with my anger roots

Growing up as the only Latina in my friend group or school, I was often told I was sassy, feisty and angry. I never understood what any of those words meant. I knew I had anger. So much of it. I needed to go back to my anger roots. I would make a genealogy of anger, or an anger family tree to attempt to uncover my anger genetics, talking with my grandmother about her mother and her mother’s mother. What came out of this was a 12-minute, 3-channel video made in collaboration with 25+ women from all over the world, in which each person had a chance to express corporeally how their anger manifests.

Warning: this video contains strong language that may not be suitable for some viewers. Viewer discretion is advised. Turn down volume when viewing.

This video, which I made from 2018 to 2019, was a transformative project for me. I was very intrigued by the roots of anger, and how this one feeling can serve as a net for other emotions. Anger is an emotion we have to push down – one that is “ugly,” not zen. I wanted to embrace it in the women around me, to understand it further.

My Aunt Camila (aka Camilonga)

This story could have gone in two directions… but sometimes humour is the best medium to highlight how ridiculous something is in our society.

Stand-up comedy by Sofia Mesa, filmed by Alix Van Der Donckt-Ferrand at the Centre du Rat Talent show in a Montréal alley, July 2022

My artistic process is very organic

I often (still) carry pencil and paper with me to write or draw. I keep a daily diary in which I force myself to write one thing I envisioned that day… text, feeling, images, ideas, etc. When I take photos, there’s an intuition I feel before I shoot an image. Sometimes images come to me in dreams, or are variations of images I’ve already seen. If I feel a response from my body urging me to take a photo, I try to always take it. I love finding the nuanced moments in between shots or just before taking a shot… where, just for an instant, we inhale – and for that moment, everything stands still. I acknowledge my subject and my subject acknowledges me. And we hold each other for that single breath. The image becomes a proof, a monument to our shared moment of seeing one other. Underneath all my anger-related work (of which there is still more to come) lies a version of myself that is who I am in my deepest, most effortless self.

Making artwork is my way of making peace with the inner battles that haunt me. I don’t belong anywhere, but I belong everywhere because of it. Art is my best friend; it is my child and my mother; it is my safe space. It never judges me and it always accepts me exactly as I am. Art is the love of my life.

For more on Sofia Mesa’s work, please visit her website and her Instagram page. For a recent exhibit, see Joys Gallery.

Note to Anger painting 2:

Sofia and some of her friends found an abandoned house on the west side of Toronto, and over a period of two years, made paintings inside and outside the house. A man without housing ended up living there and contributing to their paintings, adding marks and text of his own. This was a show about the housing crisis in Toronto.