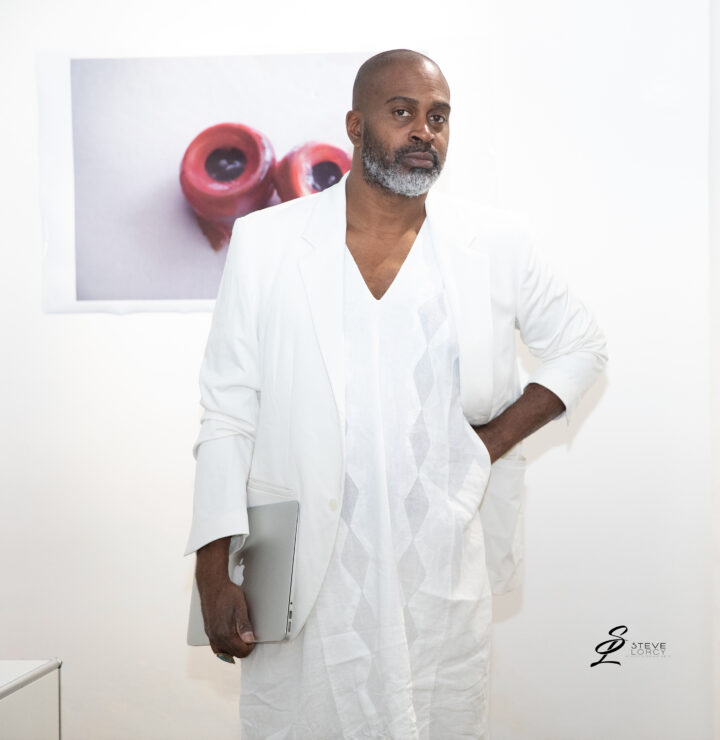

Sound artist, choreographer and performer Jassem Hindi, in conversation with James Oscar

“Jassem Hindi’s work looks at the double bind of haunting and hospitality in an effort to reveal slow (unseen and quiet) violence and slow revolutions. His last recent performances make use of the relation between performance and poems to create immersive environments and collective political spaces. His work is hybrid and extends to a variety of forms of expression.” (jassemhindi.cargo.site)

Jassem’s collaborative pieces have won numerous awards, including a Bessie for Ligia Lewis’ minor matter, featuring his sound design. His previous academic work led him to study under philosophers such as Elizabeth Thomas Fogiel, Alain Badiou and Jacques Derrida.

Introduction

The conversation’s backdrop is the war in Gaza, Jassem being Palestinian. We do not directly discuss the war but instead focus on sound and beat in configurations of authority, violence and power. Jassem and I go way back, and we frequently play with the analogy of a crime scene to analyze various kinds of situations in the arts scene and on the world stage.

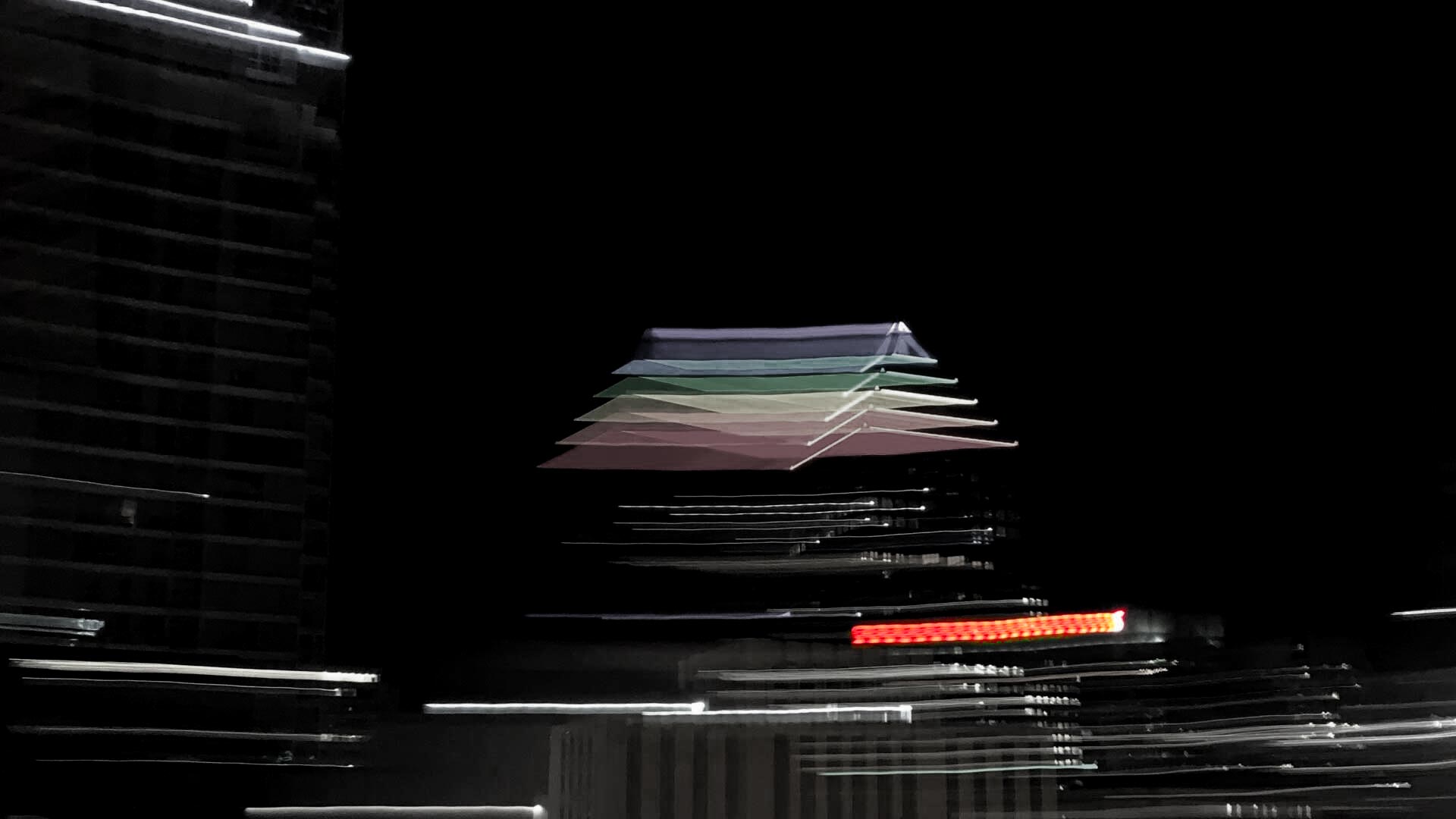

Beat, counter-beat and fugitivity… Beat as absence, the silence that generates rhythm. Removing elements creates a beat. It’s what’s chosen not to be said. Beat hides, creates and dictates what should be revealed. What’s left unsaid, what’s hidden makes beat more intricate and structural. Beat decides what’s shown or concealed, in a complex interplay of creation and concealment.

James: We’re focusing on jazz and beat as “fugitive” literature in this issue of a magazine I am guest editing this month. As you and I often analogize various situations to crime scenes—colonialism and other configurations of power’s traces (décor de la scène)—including how you and dancer/choreographer Lara Kramer design your choreographic stage with strewn objects and opaque materials for the audience to deduce, I want to discuss the body of the crime and how sound and “beat” might lie within its vicinities.

I’m intrigued by the idea of a “counter-beat.” My question is whether there is another beat that can exist in the present atmosphere of “permanent violence.” Is there actually a beat that can call out the crime, call out “something else”?

Jassem: I like the notion of a counter-beat. There is something interesting about that. Tell me more.

James: There’s the crime scene and then there is a certain fugitive quality in and just outside the crime scene, oscillating between illusion and reality. It feels like we’re in a moment of “permanent illusion” and “permanent reality.” What sound or beat might offer a counter-narrative amidst and outside this constant shift between sound and unsound?

Beat as absence, the silence that generates rhythm.

Jassem: These concepts you are bringing up have to connect to a level of real-life events. A crime but which crime? Fugitive but what fugitivity? Whose crime scene can be published without family authorization? Because there is this idea of the crime scene that was developed around the idea of police image, forensic photography… and these were crime scenes whose photos were easy to publish because these were not rich people in the photos. It’s vital these ideas ground in reality. Because the concept of the crime scene exists, sadly, out of necessity—something that necessarily happened.

In other words, when you are talking about crime scenes, it is about where and when and who. So we must ground this dialogue in something real, where it is important to know that what is being presented as articulations of some kind of situation of power and the accompanying crime scene, and all the thinking around this, exists out of necessity. We have to consider these concepts as being so necessary for thinking about these scenes of power that if we do not have them, we might die or collapse.

For me, the crime scene does not come from nowhere and thus the discussion of fugitive and “fugitivity” does not come from nowhere—it comes from the escape routes to the North during slavery for black people. Of course, we can use the concept of “fugitivity” afterwards and articulate and use it to speak about other things afterwards, but first we need to speak about its origins as a mode of resistance during slavery. In general, those constellations of concepts demand to be articulated to the real. Even when we use these ideas, they should be used with their historical contexts. The dialogue on power and crime scenes stems from a position of necessity.

James: For example, in Miami from which I just returned, the racial situation feels bleak. There’s a constant shrill loudness and complete silence—the first and last party with its own beats, swinging from extreme to extreme. Rap groups attempting to recreate a fugitive beat, but it feels futile. I wonder which beat can still “do something” in this moment of incessant chatter followed by silence. This moment of sound and unsound and for me it’s not just a concept. It’s a living reality. Where everyone is talking, talking, talking, and then all of a sudden no one is saying anything. I am interested in the beat in the interval.

Jassem: I don’t think sound can be focused by itself into just something incidental—sound being the consequence of something more holistic, like a soup of events. But at the same time, that’s what I love about sound—it does not really care about its history. I think it’s a betrayal to try and understand the trajectory and history of a sound until it is done.

Maybe [there’s a difference] in Western music, where [the outcome can be deduced] before trying to look at music as itself being some sort of historical consequence, like a reasoning, a positive object. In that case, sound and music’s history is often derived from preceding events, and music is viewed as a historical consequence, as a logical and affirmative entity.

However, for the rest of us, [music and sound are] a positive object that never assumes such a positive form. Sound comes from the shadows and a constellation of activities, and only then later someone names it. When it (sound) is named before, it’s usually just to survive. Everybody knows it’s a lie (when you try and name or reason out or label sound beforehand). People smile, like, okay that’s cool, and then next week it’s labeled/called something else.

There is something very interesting about [this]…it’s a form of fugitivity. To me that’s what fugitivity means—it is a sense of life with betrayal, life with something non-historical—not in the sense of no-history but more in the sense of understanding sound is about “later.” It is also true that we are often refused certain histories (that are suppressed) so that is important to also note. Whatever the activity, music is something that participates in the “good life,” however grim that life is. It’s part of the utopia, but what’s important is to never speak about sound. (Jokingly) The second you start to describe what a good life and what sound is, it’s over! Just like once we explain a joke, it’s over… It’s funny, we always use the word underground (for music) but never fugitive, and I think fugitive is so much truer in that sense. Because underground is a place, but what is more interesting is what happens (with the sound and music), and that is the “fugitivity.” I think it was such a find by Fred Moten to be able to articulate the idea of “fugitivity” as he did. [Ed. note: See, for example, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study by Fred Moten and Stefano Harvey, Minor Compositions, 2013.]

James: I mean, these are just words—I don’t want to reuse phrases with predetermined meanings. It’s apparent when discussing some western music (“white man’s music”). I’m contemplating a Christian telos, where there’s a predetermined story from beginning to end. But a genuine beat, a true sound, what you’re suggesting, it’s sovereign. We don’t name it, don’t package it beforehand. We don’t want to name it, don’t want anything from it, don’t want to know it in advance or attempt to possess it—it’s elusive. For Afro-descendants, that unnamed sound exists, and we’re willing to wait for it. There is this willingness to wait for the beat and see it develop and not chicken out, not feel like you’re getting bored while you wait for the beat to develop and finish. We simply follow it wherever.

Jassem: It has this patience in a way. I always found it really hard to think of sound as an afterthought, thinking of sound after having thought about something else. It has this digestion, a digested sort of [quality]… like you ruminate everything and there is the sound? If you think about it for too long, there is labour, and then there is…

the circularity of breath, the art of hiding in plain sight

it just comes as the necessity—it comes as a necessary form of expression in a way, but an expression really in the way of expecting a thing? And of course, in and of itself, it’s more about potential, it creates more possibilities. This is actually very interesting because it’s very hard to think about what is the temporality of sound. Is it something that comes in waves afterwards, or can we deduce one sound from the next, can we deduce one musical movement from the one just before? I think any linear understanding of sound is just going to be self-serving. But there is something very interesting about the hospitality technique of certain music. For instance, I am thinking about long cycles of breath in sound—music with very long cycles, low and trance-like or with a purpose of trance. I think that in those, you feel like you are always invited, that you can kind of sing along.

The thing is that is only true until you have to participate live, where at times it is only for the initiated and the only people who do it are the initiates. It’s not just something you can reproduce even if the rhythms are really simple. I like the technique of survival in all of this—the circularity of breath, the art of hiding in plain sight.

James: To me, it seems like you’re discussing intervals. I delved into disco music and my personal connection to it, which is profoundly tied to emotions. In a moment of emotional expression, I found myself drawn to the notion of intervals—riding along with the music. When you mention being invited in, it’s almost like the underground railroad—an invitation to move freely, almost like a graceful “snaking.” I like this idea of the kind of sounds that are not exclusive but inviting you in.

Jassem: It is interesting to think of it in terms of intervals.

James: What would you say distinguishes sound from beat?

Jassem: I love the idea of beat as a way to replace music. I love everything when it comes to sound but I especially like to see very sharp edges like mini revolutions in the sound. I like the idea of thinking that beat is a sort of attempt to replace the entire kingdom of music with something else called “beat.” There is something very joyful and vengeful and very liberating (about a “beat”). To say this is music, this was music, and this is “beat,” and the rethinking of sound from there. Not in this kind of regularity of interval or predictability or tricks, or some idea of schools of music like Afrobeat.

I think of “beat” as a kind of big revolution. I think about “beat” as tricks—this idea of carving, this idea of fabricating—that you are building something and then you just pass it along and play with it and keep playing with it. I also think of beat as something very collective. Someone starts it and then the next person picks it up. It can be virtuosic or abstract or experimental but it still can be picked up by someone else. Beat has a completely different agenda, different dialect.

James: What I like about what you say about beat is that we could make one beat now and that beat could replace the whole history of music.

Jassem: There would be something that everybody can latch on to… Beat being its own outside. Music is always looking towards itself. It’s generating its own internal theories like deducing itself from itself, whereas when I think of beat, I always think of something like a barnacle on a rock. Think of beat being tied to various things—beat and cooking, beat and fixing a garden, beat and another kind of labour that is happening at the same time as beat. I do hate this constant association that hip hop is urban. It’s not urban. It’s not trying to reproduce the sound of what’s happening around in the city. It’s not trying to imitate the outside world. It’s inciting itself…

Silence then as the maker of rhythm, rather than sound as the maker of rhythm.

There is also something about beat where it is not crescendo. It’s like a snap of a finger even if you are doing a crescendo. The spirit of beat is, “First you break the glass—it always starts with a bit of a bang. It’s good at hiding this. Beat is not feminine or masculine where it presents itself as something really loud and very strict and kind of unidimensional. It is not that. I think of it as quick and good at surviving, in a way. It introduces itself with a bit of time in a charming and smooth way, then reads the situation knowing [that] next time and [at the next] moment it might need to be faster and louder. I think of beat as a stick under the drum.

James: It sounds like beat has more information in its one second than a long song.

Jassem: Exactly. This is a basic analysis but imagine re-complicating and re-articulating this. Think about beat as the absence. When I talk to my students about rhythm and also as a preamble to speaking about silence, I say to them:

(1) You have to think of rhythm as having a regular interval and you never miss the beat. Decide on the size of the interval then you have a rhythm. The beginning and the end of each interval, and that is rhythm.

(2) Another way to think of sound is to not think of it as a positive thing but to think there is always constant sound. You will be basically beating your drum constantly, and what makes it rhythm is when you stop. So instead of thinking of beat as the marking of the interval, remove the entirety of that concept and think instead of when all stops. Silence then as the maker of rhythm, rather than sound as the maker of rhythm.

James: And where does beat come in?

Jassem: The same idea. Instead of thinking of beat as generating presence and a product, see beat as this idea of removing, what you take off. Everything you take off the table then generates the beat. Like when someone raps and is crafting the beat while narrating a story as they go along. They are also choosing what they are saying and what they are not. Beat then in this case is what is not—what they decide to not tell you. And if you know about it, you know it is there. What is withheld is a much more complicated beat for you, but if you don’t know about it, it’s less interesting. And in fact, the person who makes the beat may not know which beat is more important than the other. Beat then is something that is making and hiding rather than something that is producing. It is there, then, that you enter more into the virtuosic part of beat. Beat is slowing down, reverberating, constantly masking, holding back, backtracking, avoiding—then you get what beat is… Beat decides what should be shown or not shown!

Jassem Hindi’s art encompasses sound, choreography, performance, writing and storytelling. Born in 1981 in Djeddah, Saudi Arabia, to a French mother and a Palestinian father, Jassem is of French and Lebanese nationality and lives in Norway. He served as Artist in Residence at the MAI (Montréal, Arts interculturels) for the past three years (2020-2023). Find out more about Jassem’s work on his website.