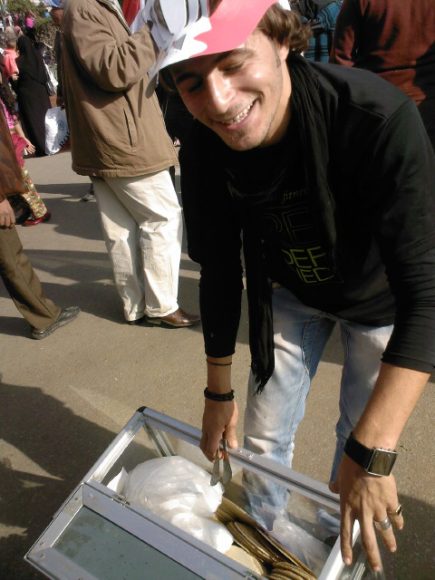

The ambience of the demonstrations at Tahrir Square combined revolutionary edge with festive elements and scathing political humor. For example, the festive features of the moulids (popular festivities celebrating the birth of one saint or another that span the whole year across Egypt) were all rallied to the cause of El Thawra (the revolution): peddlers of all kinds of snacks, from popcorn to sweet potatoes, to nuts, seasonal fruits and vegetables and freska ( cookies typically sold at Alexandria beach during the summer as well as tea, coffee, soft drinks and juices. (168 and 177)

And like the moulid, there were people visiting from remote towns setting up all kinds of improvised tents and spreading worn-out blankets and bed sheets covered with holes, whole families with their children, older men and women (188, 189)

The colorfulness of the moulid deferred to the flag’s trio of red, white and black which glowed on every shape and form of the flag and on all the paraphernalia of El Thawra: tag necklaces, head bands, paper whistles and cone- shaped hats, tiny purses for “the young girls of El Thawra”, flags ornamented with golden braids in honor of “the ladies of El Thawra”. (166 and 176).

Humor took many forms e.g. the popular zar (a ritual of exorcism of evil spirits) was given a hilarious twist as dervish-like circles of people performed the ritualistic dance typical of the zar tradition and recited incantations tailored to the occasion, for instance, asking Mubarak to step down “Get lost. Get lost.” and to chase away the evil spirits menacing El Thawra. A huge poster featured “The National Team of Robbers” listing the corrupt figures crowned by the “coach” Mubarak , and the sums of money usurped by each (197).

Humor also came through jokes e.g. Mubarak was told by his ministers that Friday had been declared “The Friday of Departure” , Mubarak answered, “What do you mean, are the people going away somewhere?”; there were humorous slogans addressed to Mubarak e.g. “Please step down! My wife wants to deliver and the baby doesn’t want to see your face.” as well as stand-up comics.

Families joined with their children as the profile of the demonstrators expanded day after day to include people of all ages and classes who poured into Tahrir Square in solidarity with the youth who ignited the first flames of the revolution. 180

Banners carrying vernacular poems encapsulating the grievances and demands of the people were everywhere. This particular banner denounces the rampant systematic neglect and usurpation by Mubarak’s regime of the country’s wealth: Enough is enough! Stop suffocating us; stop robbing us. You made us sell our beds and sleep on the floor. Enough is enough! Stop starving us. Stop impoverishing us. Enough is enough! We are waking up. We are claiming our rights in a peaceful revolution. Mr. General Prosecutor, we want our money back! 181 Down with the State Security Apparatus! 183

There were accounts of victims of torture and some of the typical state security officers’ statements reported by political prisoners routinely subjected to torture: “ If God descends from the sun, you will be released from prison.” ; “ People are a bunch of dogs; we are your masters you sons of bitches.” 193

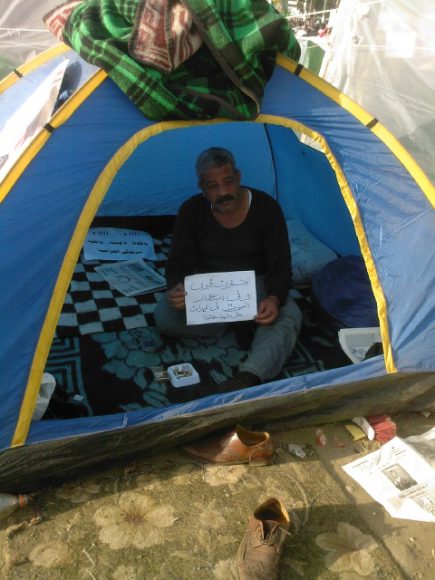

The foremost demands in the revolution were democracy, freedom and the dignity stampeded by a ruthless police state. This reclamation interestingly preceded social justice in the order of priority among all classes and belied the assumption that a revolution in Egypt would certainly be led by the overwhelmingly poor, in what were referred to as “riots of the starved from the shanty town belt in Cairo.” The banner of this old, poor demonstrator says: I have dug my grave with my own hands here at Tahrir. Give me freedom or bury me here. 190

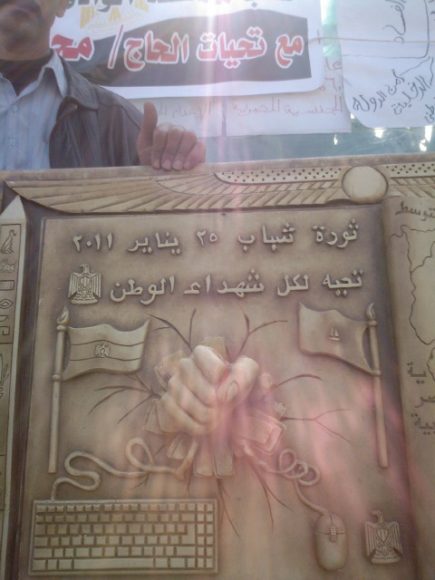

A mural depicting the map of Egypt paying tribute to the martyrs of the revolution 172

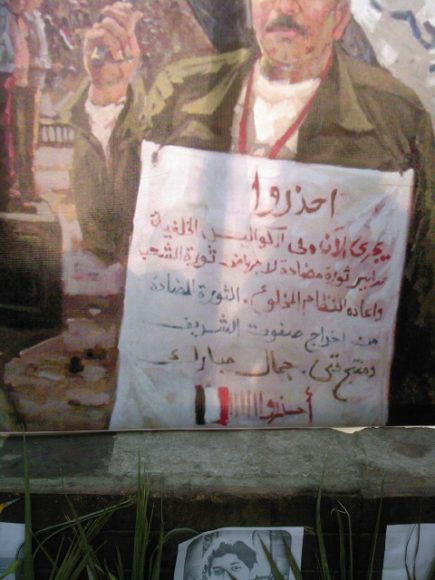

A painting inspired by the revolution with a warning attached: Beware a counter- revolution is in the making by supporters of the toppled regime and the State Security apparatus. 170

The ambience of the demonstrations at Tahrir Square combined revolutionary edge with festive elements and scathing political humor. For example, the festive features of the moulids (popular festivities celebrating the birth of one saint or another that span the whole year across Egypt) were all rallied to the cause of El Thawra (the revolution): peddlers of all kinds of snacks, from popcorn to sweet potatoes, to nuts, seasonal fruits and vegetables and freska ( cookies typically sold at Alexandria beach during the summer as well as tea, coffee, soft drinks and juices. (168 and 177)

And like the moulid, there were people visiting from remote towns setting up all kinds of improvised tents and spreading worn-out blankets and bed sheets covered with holes, whole families with their children, older men and women (188, 189)

The colorfulness of the moulid deferred to the flag’s trio of red, white and black which glowed on every shape and form of the flag and on all the paraphernalia of El Thawra: tag necklaces, head bands, paper whistles and cone- shaped hats, tiny purses for “the young girls of El Thawra”, flags ornamented with golden braids in honor of “the ladies of El Thawra”. (166 and 176).

Humor took many forms e.g. the popular zar (a ritual of exorcism of evil spirits) was given a hilarious twist as dervish-like circles of people performed the ritualistic dance typical of the zar tradition and recited incantations tailored to the occasion, for instance, asking Mubarak to step down “Get lost. Get lost.” and to chase away the evil spirits menacing El Thawra. A huge poster featured “The National Team of Robbers” listing the corrupt figures crowned by the “coach” Mubarak , and the sums of money usurped by each (197).

Humor also came through jokes e.g. Mubarak was told by his ministers that Friday had been declared “The Friday of Departure” , Mubarak answered, “What do you mean, are the people going away somewhere?”; there were humorous slogans addressed to Mubarak e.g. “Please step down! My wife wants to deliver and the baby doesn’t want to see your face.” as well as stand-up comics.

Families joined with their children as the profile of the demonstrators expanded day after day to include people of all ages and classes who poured into Tahrir Square in solidarity with the youth who ignited the first flames of the revolution. 180

Banners carrying vernacular poems encapsulating the grievances and demands of the people were everywhere. This particular banner denounces the rampant systematic neglect and usurpation by Mubarak’s regime of the country’s wealth: Enough is enough! Stop suffocating us; stop robbing us. You made us sell our beds and sleep on the floor. Enough is enough! Stop starving us. Stop impoverishing us. Enough is enough! We are waking up. We are claiming our rights in a peaceful revolution. Mr. General Prosecutor, we want our money back! 181 Down with the State Security Apparatus! 183

There were accounts of victims of torture and some of the typical state security officers’ statements reported by political prisoners routinely subjected to torture: “ If God descends from the sun, you will be released from prison.” ; “ People are a bunch of dogs; we are your masters you sons of bitches.” 193

The foremost demands in the revolution were democracy, freedom and the dignity stampeded by a ruthless police state. This reclamation interestingly preceded social justice in the order of priority among all classes and belied the assumption that a revolution in Egypt would certainly be led by the overwhelmingly poor, in what were referred to as “riots of the starved from the shanty town belt in Cairo.” The banner of this old, poor demonstrator says: I have dug my grave with my own hands here at Tahrir. Give me freedom or bury me here. 190

A mural depicting the map of Egypt paying tribute to the martyrs of the revolution 172

A painting inspired by the revolution with a warning attached: Beware a counter- revolution is in the making by supporters of the toppled regime and the State Security apparatus. 170