plink, drip, drip, drip, drip, drip, drip plink, drip, drip drip drip drip I hate the sound of raindrops on the roof. So insistent, loud, abusive. Noise is invasive— overpowering the senses. Angry noise dominated my family. As a child, it sent me burrowing under beds and into closet corners. At 14, I gave up talking back. I swallowed my voice and went silent. A relief. The World Health Organization has found that “children who come from noisy or chaotic households can experience increased anxiety.” (WHO) Strangely, I worried about birthday parties. I feared balloons bursting, finding the sudden noise intolerable. Later, I discovered a word for this: globophobia, a fear of balloons. Watching someone blow up a balloon can disturb a person with ligyrophobia, a fear of or aversion to loud sounds.

Balloons

Never touched

but the sound of his rage

bruised her skin

She would forever shrink from sudden noises

balloons bursting

children shrieking

doors slamming

Solace in closet corners

arms wrapped around knees

body tight

head bent against invasion

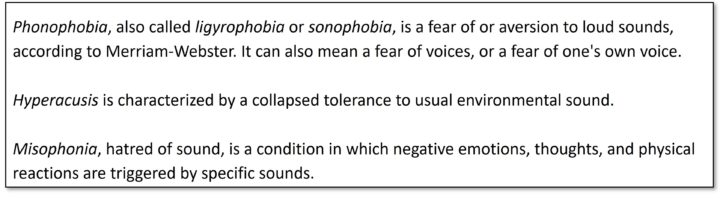

I am misophonic, globophobic, phonophobic and suffer from mild hyperacusis. I embrace these labels. I’m part of a community of noise sufferers, diagnosed with “conditions” with luscious names. My own voice does not scare me.

My collection of earplugs is exhaustive: in blues and purples, orange foam, white moldable silicone, striped yellow and red tubes, and swimmers’ plugs that look like fusilli pasta. I carry earplugs in every pocket and bag, and never hesitate to use them. I delight in the strangeness of orange foam sticking out of my ears. As the foam slowly expands, the world calms and I can feel my way forward.

I am considering starting the first chapter of the Society of Noise Resisters and Silence Warriors (SNRSW). New members would receive a free mug.

The Crusades

I am persistent and dogged. I draw on a bottomless well of strategic anger to challenge inconsiderate and invasive noise. In North American culture, radical individualism—insidiously popular—encourages a sense of entitlement to infringe on and invade the soundspace of others.

Recently, on the lakefront bike path in Toronto, a man had a blaring radio attached to his bicycle. Rather than birdsong and trees humming, we had to listen to this noise.

“Plug it in your ear,” I say.

“Fuck off,” he says.

I undertake my own small crusades; although justified, they are mostly fruitless. Often enough, I consult noisenuisance.org, which provides advice from environmental health professionals on tackling noisy neighbours.

Crusade One: Dogs Barking

To the dog owner at xxx Brunswick Avenue, Toronto:

We appreciate that you love your dog. However, we’re shocked that you leave your pet unattended and barking for hours at a time. We imagine it is a sad and lonely time for your animal. We also find the noise intrusive and disturbing, both inside and outside our house.

The city is a shared and crowded space and its survival depends upon respect for others.

We have asked you a number of times not to leave the dog unattended. Next time, we will complain to the Animal Control Services of the Noise Control Branch at Toronto’s City Hall.

PS. We encourage you to check out http://www.barkingdogs.net/. It might surprise you that this organization sees the “acoustic blight of chronic barking” as a public health emergency.

Thank you. Your Neighbours

City By-Law: “Persistent barking, calling or whining or other similar persistent noise-making by any animal kept or used for any purpose is prohibited at all times.” Call 338-7297(PAWS).

Devastation

I suffer from noise pollution. I am not alone. But the catastrophic impact of noise is often dismissed, buried, concealed.

Poor urban neighbourhoods are nearly two decibels louder than affluent areas. Access to silence is yet another class and race privilege.

According to The Environmental Guide:

“Exposure to prolonged or excessive noise causes health problems ranging from stress, poor concentration, productivity losses in the workplace, communication difficulties and fatigue from lack of sleep, to more serious issues such as cardiovascular disease, cognitive impairment, tinnitus and hearing loss … In 2018, WHO found that, each year in Europe alone, at least one million healthy years of life are lost due to traffic noise.”

Les Blomberg, from the Noise Pollution Clearinghouse, points out:

“What we’re doing to our soundscape is littering. It’s aural litter—acoustical litter—and, if you could see what you hear, it would look like piles and piles of McDonald’s wrappers, just thrown out the window.”

The effect of human-generated sound on non-humans is more than devastating.

Fireworks terrify. Animals panic. Coastal birds fly far out to sea and are unable to return. In Arkansas, thousands of blackbirds fell from the sky following the 2011 New Year’s Eve fireworks. Loud noises cause caterpillars’ hearts to beat faster and bluebirds to have fewer chicks.

In the North Pacific Ocean, underwater noise has doubled in intensity every decade for the past 60 years. Ships, oil drills, sonar devices and seismic tests have made the once tranquil marine environment loud and chaotic. Excess noise interferes with the ability of whales and dolphins to effectively echolocate and can cause mass strandings of whales on beaches. Sometimes, frightened whales bolt toward the surface and die of decompression sickness.

I lament the indiscriminate ravaging of the natural world through noise, the anguish and suffering it has caused.

Crusade Two: Dogged Persistence

To: The Editor, Globe and Mail

Since 1949, every Labour Day weekend in Toronto has been ruined by the Air Show at the Canadian National Exhibition (CNE). Friday to Monday between 12 and three pm, the entire city of Toronto is bombarded by the piercing sound of planes. The noise is paralyzing, terrifying, deafening, even inside … Should such an invasion of public soundspace be permitted? Should the peace of the majority be trumped by the pleasure of a few?

This letter was not accepted for publication.

The CNE responds to complaints with an email form letter, which admits that noise “can be disruptive for people in the vicinity.” In the vicinity seems code for the three million people who live in the city of Toronto. In their reply, they request that readers be environmentally friendly and not print out the email.(i)

I now leave town on Labour Day weekend.

Gallimaufry

This gorgeous word means “a jumbled mix of things” (from mid-16th-century archaic French). For years, I have collected snippets about noise and silence—a gallimaufry. Each is like a piece of green glass worn smooth by waves, found on a beach, and pocketed and treasured.

A sign on the wall offers an unexpected delight during a visit to the Bodleian Library in Oxford. The library opened to scholars in 1602, the circular domed building like an ever-entwining Celtic knot. The Statute of 1645 forbade the removal of any book.

The air is heavy with history: leather-bound books worn smooth, shelves gleaming with polish and the softness of age, carved wooden ceilings, illuminated manuscripts thousands of years old and still glimmering with gold leaf.

My eye catches the sign, hung askew on the side of a bookshelf, unobtrusive, dignified, understated, carrying the legacy of centuries of noise.

Restaurant noise is ubiquitous, sound levels too high for conversation or intimacy. Increasingly, my community of friends avoids going out to eat.

If we lived in New York, we could visit Burp Castle, the self-styled “temple of beer worship,” with its medieval-style murals, bartenders dressed in monks’ robes, and Gregorian chants over the sound system.

In 2019, in order to preserve the sounds of extraordinary violins, the Museo del Violino in Cremona, Italy, recorded every possible note that could be played on four prized instruments: Girolamo Amati’s violin crafted in 1615; two violins by Antonio Stradivari (himself from Cremona), one from 1700 and one from 1727; and a 1734 violin by Guarneri del Gesù.

Complete silence was required. The whole town took a vow of silence to ensure that the 32 hypersensitive microphones did not pick up any sounds from the street: neither the rumble of a suitcase dragged across cobblestones nor the hiss of a street-sweeper machine. In the concert hall where the recording took place, the light bulbs were unscrewed in order to stop their tiny buzzing sound.

In the first and second centuries, Japanese dōtaku (銅鐸)—bells made of thin bronze and richly decorated with dragonflies, praying mantes and spiders—were buried to ensure a community’s agricultural fertility. Counter-intuitively, these bells were mute. They embraced silence.

Paradox (I)

In music, silence is prized. Debussy is supposed to have said, “Music is the space between the notes.” And apparently, Mozart said, “The music is not in the notes, but in the silence between.” Musicologists talk about mystical silence, dramatic silence, liminal silence, attentive silence, explosive silence, silence-as-sound-painting, and the emancipation of musical silence.

Composer John Cage hated Muzak, which, for him, was proof that silence was going extinct.

He wrote that he wanted “to compose a piece of uninterrupted silence and sell it to Muzak Co.” In 1952, Cage premiered 4’33. The score instructs the performers not to play their instruments during the entire duration of the piece—four minutes and thirty-three seconds.

Cage would have liked Quiet Corners—a website that identifies places free from piped music.

Perhaps Cage would have also liked these lines from “Keeping Quiet” by Pablo Neruda:

If we were not so single-minded

about keeping our lives moving,

and for once could do nothing,

perhaps a huge silence

might interrupt this sadness

of never understanding ourselves

and of threatening ourselves with

death.

The pleasures of silence are not without contradictions.

Silence, Silence(d): Paradox (II)

Silence(d) is not the absence of noise but the absence of voice. Who silences? Who is silenced? Who silences whom? Why?

I spent most of my life as a teacher. Despite embracing silence in so many other parts of my life, it took me years to get curious about student patterns of speaking and silence.

Influenced by metaphors of voice and breaking the silence, I used to think that it was my responsibility as teacher to encourage, even ensure, that everyone participated in classroom discussions. In many, many instances, I cajoled and implored students to share their thoughts, sometimes successfully and more often not. My own discomfort with these appeals and students’ obvious resistance to them finally encouraged me to begin a dialogue with students about silence.

What emerged was the multiplicity of silences operating in classrooms: silence due to fear and intimidation; silence from shame, from undervaluing oneself and one’s knowledge; silence that preserves privilege and avoids risk; silence that refuses responsibility to the group and to the collective learning process; silence that is about listening and sharing space and that builds the classroom collectivity; and silence that actively resists oppression.

King-Kok Cheung in Articulate Silences emphasizes that the privileging of speaking over silence is Eurocentric: “Silence, too, can speak many tongues, varying from culture to culture.”(ii) In Japan, haragei (wordless communication) is more highly valued than eloquence, an intriguing alternative to our culture’s incessant noise. In her essay “The Aesthetics of Silence” (1967), describing “the art of our time,” Susan Sontag wrote: “One recognizes the imperative of silence, but goes on speaking anyway. Discovering that one has nothing to say, one seeks a way to say that.”

Dark Silence

Eerie. No answer. No reply to message left. No prompt email. In the COVID context, silence is unnerving, alarming.

Crusade Three: Leaf Blowers

The gas-powered leaf blower fills the soundspace, even with the windows closed. These toxic machines can emit a sound level of up to 112 decibels (a plane taking off generates only 105 decibels). Even at 800 metres away, a conventional leaf blower is still over the 55-dB limit considered safe. Gas-powered leaf blowers will soon contribute more to smog in Los Angeles than automobiles.

During the Toronto winter, I live in Palm Springs, California, which has a public ordinance banning these blowers. Too often, it’s ignored. Today, I try earplugs. Useless.

I complain to the homeowners’ association. The landscaper protests about added expense and decreased efficacy. However, by the end of the day, he agrees to buy an electric blower to comply with the law.

Small victories.

The Quiet Communities movement, whose mission is “to transition landscape maintenance to low noise, low impact practices,” documents the burgeoning threats by the landscaping industry. The industry uses the courts to fight local efforts, but they have always lost!

Sound victories.

Silent Pleasures: Paradox (III)

In Mission Creek Preserve in California, I hear the sound of nature’s silence—the distant chirp of a bird, the humming conversation between the creosote and the mesquite, the waves of wind. A comfort.

Soundwalking is an intentional listening to the environment, an exploration of “the sonic ecologies of place.”

I dream of quiet gardens. On a world map, over 300 quiet gardens in the UK, Europe, Africa, Australasia and North America are marked. Havens.

The Quiet Garden Movement speaks of “intentional space for inner silence.”

I dream of the labyrinths in quiet gardens at Epiphany House (Cornwall), Friedenskapelle (Austria), St John’s Quiet Garden (Ontario), Woodlea (County Durham), Cathedral Rain (Iowa), Green Acres Ceremonial Park (Buckinghamshire), El Jardin del Labirinto (Spain), Quiet Garden (Cyprus), and Eglwys St Michael Llanfihangel Rhos-Y-Corn (Wales).

I draw a finger labyrinth to settle my mind. To find a moment of silence

Empty Space

evokes silence

Silence, Singing

Silence calms the heart and grounds the body.

Silence is a meditation.

It has the cadence of a poem.

Silence is a daydream.

Silence is the taste of spring flower honey

the velvet touch of a rose petal

the scent of night-blooming nicotiana

Silence makes my heart sing, quietly.

Noise Resisters and Silence Warriors

The individuals and organizations listed below are all offered a free membership in SNRSW. A toast to noise resisters and silence warriors!

In her research, eighth-grader Nora Keegan from Calgary learned that a child who says hand dryers “hurt my ears” is correct. She studied the risks to hearing from 44 hand dryer models at arenas, restaurants, libraries, schools and shopping malls. She found that sound levels were much louder at children’s ear heights, and much higher than peak levels recommended by Health Canada. In fact, they are “very loud, around the level of a rock concert,” Keegan said, “louder than Health Canada’s regulation for children’s toys.” At age 13, she published her findings in Paediatrics & Child Health.

Small revelations.

The Right to Quiet Society for Soundscape Awareness and Protection, a Canadian charitable organization, was established in 1982. They recognize that the right to quiet is a basic human right, rather than “an amenity for the affluent.”

As one of my crusades, I encourage people to join the collectives of people who fight against noise and embrace silence. Print out these cards and leave in noisy and quiet places.

Every April since 1996, a student-led national protest invites students to take a day-long vow of silence to highlight the erasure of LGBTQ people in schools. The event is sponsored by the Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network, which includes more than 1.5 million students, families, educators, and education advocates working to create safe schools.

Small but important victories.

A Finnish watch company, Rönkkö, launched a slogan: “Handmade in Finnish Silence.” Rönkkö’s website points out that for a Finn, “Silence means time for thought; creating something out of nothing.”

In an article about the effects of silence on the brain published in Nautilus, Daniel A. Gross recounts: “One icy night in March 2010, one hundred marketing experts piled into the Sea Horse Restaurant in Helsinki with the modest goal of making Finland a world-famous tourist destination.” The marketers, Gross writes, concluded that “silence could be marketed like clean water and wild mushrooms. Silence is a resource … In the future, people will pay for the experience of silence.” In 2011, the Finnish Tourist Board released a series of photographs of lone figures in the wilderness with the caption, “Silence, Please.”

Burger King in Finland launched a completely silent drive-thru, which is very popular with the Finns. Check out their video on Vimeo.

Small victories on the corporate front.

Contemplative Silence

On a trip to Japan decades ago, the calm quiet of the monasteries was compelling, addictive. Many were only accessible by climbing arduous stairs. In Yamadera, there were 1,015 steps to the Okunoin (main hall) of Risshakuji Temple (立石寺).

Is the pleasure of silence enriched by the struggle up the stairs?

Is writing about silence a way of living with noise?

Is the call for silence comfort enough?

Silence, please. Please.

For more on Linda Briskin’s work, please visit her website.

i Every country needs an organization like the UK Noise Abatement Society (NAS), which lobbied the Noise Abatement Act through Parliament in 1960, establishing noise as a statutory nuisance. The NAS worked with industry to encourage the production of quieter goods, with academics and scientists to identify the issues and research possible solutions, and with government to transform policy and effect change.

ii Cheung, King-Kok (1993) Articulate Silences. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, p. 23.