Teesri Duniya Theatre was established in 1981 by Rana Bose and me as co-founders. Others involved were the cast and crew of the company’s launch production, Badal Sircar’s Julus. At the time, there was no other South Asian theatre company in Montréal, and the notion of political theatre, mention of Indigenous people, and cultural plurality were confined to obscurity in the Canadian theatre world.

Canada remains acutely aware of its bi-colonial heritage divided by language, which leads it to produce bi-national performances, in English or French, with self-definition and self-interest as its major concerns. In the Canadian art world, Indigenous people are studiously ignored, and cultural diversity has until very recently been perceived as subsidiary. With Canada coming to acknowledge cultural pluralism with the institutionalization of multiculturalism in the 1970s, and Québec becoming more secular with the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, we saw the emergence of a relatively more radical drama attempting to analyze its post-colonial status in terms of class, gender and ethno-nationalism. Even though multiculturalism was relegated to a secondary status, it gave birth to many culturally diverse theatre performances with political consciousness that were unafraid of intervening in the process for social change.

Teesri Duniya started out as one of the very few theatre companies in Canada with a decidedly political mandate. The company’s maxim, “Change the World One Play at a Time,” derives substance from the fact that theatre by its very nature is a subversive attempt to challenge oppressive powers and affect change within society. However, it is necessary to distinguish this political theatre from the readjusted colonial political drama of dominant cultures, namely due to the fact that the two have evolved from different historical experiences and hold different world views. Similarly, it is necessary to distinguish it from several newly recognized culturally diverse theatres and practitioners whose politics merely display a show of performative pro-diversity that does not truly address social issues or enact social change.

Political theatre is inextricably tied to change in its alignment with social justice and struggles against powers that deny human beings their individual and collective dignity. It is primarily concerned with power – how people, communities and organizations struggle for it against the dominant culture of the oppressors. Theatrical performances serving to equalize power imbalances could be considered a site of subversion, where the struggle for human dignity and justice is staged with quality and aesthetic. One can imagine that social change itself is a political performance, one in which transformation is witnessed as reflection, representation through a dialogical exchange critiquing social, political, and economic conditions that keep people imprisoned in poverty, underdevelopment, and cultural oppressions. In many cases, political performance does not only offer awareness but advocates an alternative course of action.

The idea of “performance as change” arises from three primary streams of theatre practice: 1) the power of theatre and the role of culture/counter-culture in struggle for justice; 2) critical questioning of performances that primarily emphasize the upper classes at the expense of what afflicts the deprived majority; and 3) replacing conventionally prevalent presentation of issues with a more radical and sharp-edged examination. There is an active interface between performance and desired change, demonstrating how theatre could be politically transformative rather than a stagnant cultural amusement.

With those ideas, Teesri Duniya produces politically relevant theatre dissecting a number of uncommon, contentious and life-affecting issues including issues ordinarily ignored by conventional theatres. Our plays address themes such as minority and Indigenous rights, discrimination, torture, gender violence, genocide and human rights. Doing so, these plays highlight the role of theatre as a campaigning vehicle for change.

I would like to illustrate some examples of the type of changes that have been accomplished by Teesri Duniya.

Changing the Narrative

Despite the institutionalization of multiculturalism as a state policy, Canada continues to function as a bi-cultural country treating multiculturalism as a minority component and concern. Bi-cultural hegemony continues, forcing artists of colour to attune their cultural representation in accordance with the tastes of producers from the dominant groups and available patronage. Dominant Anglo and French producers consider minorities “exotic beings” and their presence suitable primarily for colourful festivals, folkloric dancing, one-night variety theatre, religious rituals, exhibits, and food shows. Emphasis is placed on visibility but not necessarily on the aesthetic and high artistic quality of their creative work.

Teesri Duniya is among the many art organizations that, through its active challenging, changed the “exotic” representation of multiculturalism from food, costumes, ancient habits, and reminiscences of cultural roots to a cultural framework for telling stories of peoples, cultures, and communities eclipsed by the dominant national theatres. It used multiculturalism as a context to create stories concerned with social justice. It critiqued culture along with other determinants of human development e.g. race, class and gender. This was an important change resulting in the development of culturally sensitive stories, de-marginalizing visible minorities, and reforming casting practices.

Reformed Casting Practices

Under the guise of quality and excellence, colour-blind casting in theatre is a Western norm. For big theatres, colour-blind casting has become a powerful excuse to use white actors for the parts written for non-whites, but never the reverse. Behind the facade of colour-blind casting, many Anglo-French (particularly French) companies use white actors to represent non-white characters simply by the usage of heavy makeup or an outright painting of their faces. This practice is justified by the long-standing excuses of an actor’s abilities, range, and artistic freedom. Teesri Duniya defied colour-blind casting practice and encouraged other companies to do the same. Colour-blind casting promotes an assimilationist view that the dominant culture is a unified whole, denying visible minorities their particularities, political standings, and personal values.

There is no such thing as colour-blindness. When audiences watch a play, they do not only see the actors’ colour, but are concurrently made conscious of social, historical, political and cultural differences. For this reason, at Teesri Duniya, we practice multicultural, multi-ethnic casting and present plays that tell stories about culturally diverse communities.

Career Development – Artists

Redefining the multicultural narrative has created conditions necessary for artists of colour to succeed in their field by creating works written for them, with them in mind, and subsequently played by them. Teesri Duniya has prepared many artists for entry into the industry and featured numerous artists of colour who are rarely given the opportunity to act in mainstream productions. Some of these actors include Tova Roy, Shalini Lal, Prasun Lala, Anurag Dhir, Amena Ahmad, Maya Dhawan, Ranjana Jha, and Aparna Sindhoor of South-Asian descent; Emilee Veluz, Cecile Cristobal, Elizabeth LaFranco and Carolyn-Fe Trinidad, of Asian descent.

With the Québec premiere of Anusree Roy’s play Letter to My Grandma, Teesri Duniya played a formative role in launching the career of South Asian actress Saher Bhojani, who graduated from the National Theatre School (NTS). Bhojani said that during all her years at the NTS, never once was she taught anything on her culture.

Arab-Canadian actor Abdel Abdelghafour Elaaziz played his first English lead role in the play Truth and Treason (2009). Since then, he has acted in many plays and films both in French and English. Actor Mohsen El Gharbi made his English language debut in our play The Poster and has since performed both in English and French as well as written and staged his own new plays. Natalie Tannous, an Arab-Canadian actress, launched her career in State of Denial, and has been a busy actress performing and travelling across the country since then. Filipino-Canadian actress Emilee Veluz played a character of her own culture in Teesri Duniya’s production of Miss Orient(ed) for which she won the best actress award and has since been quite active. Similarly, after performing for the first time in Miss Orient(ed), Carolyn Fe-Trinidad formed her own production company called AltaVista Productions, and has won awards, appeared in commercials and acted on major stages.

In addition, we presented directors Arianna Bardessono and Deborah Forde with directorial debuts in Truth and Treason and State of Denial, respectively. Bardessono won the John Hirsh prize. Deborah Forde has directed many plays since then and continues to mentor young artists across Montréal.

Changing Lives – Aiding Refugees

While Teesri Duniya has produced over 55 plays professionally that have conveyed strong social messages, it has also produced several participatory and other forms of theatre to inspire social change. Through this, it has expressed educational messages, facilitated reconciliation and encouraged audiences to tackle problems faced by their community.

For example, the company uses techniques of oral history to help the resettlement of refugees. James Forsythe interviewed over 21 Syrian refugee families and presented their stories verbatim in Arabic, French and English in the play To Stand Again. Syrian families were present for the performance and exchanged views with the audience, making it a genuine two-way communication and collective moment of sharing. The entire process helped to heal the trauma experienced by refugees and facilitate their integration into their new homes. Furthermore, through the verbatim play, audiences developed a better understanding of the lives of the Syrian families depicted onstage. As was evidenced, the healing effects of storytelling are important for empowerment, meaning-making, identity formation and even collective recognition of social injustice. It allows both the refugee families and the play’s audience to discover new potential within themselves and experience new ways of perceiving reality.

Changing Discourse

Teesri Duniya has diversified diversity. Beginning as a South Asian company producing plays primarily in Hindi, today Teesri Duniya is one of a handful of culturally inclusive companies producing plays about diverse communities, cultures and identities that make up today’s world. It selects plays based on their ability to provoke critical thinking, bring communities together and encourage positive participation from this world’s hushed voices. The selection represents relevant plays of the highest possible quality, exploring the human condition at its darkest and most pressing but also at its brightest and most jubilant junctures. Ultimately, the company’s plays point fingers at political powers and examine competing truths rather than mere conflicts.

Teesri Duniya’s contribution to performance as change is well explained in the body of plays it has produced. Notably, on the occasion of its 25th anniversary (2006), the company produced a season of plays titled “Staging Peace in Times of War” in response to the US-led war against Iraq and Afghanistan in the aftermath of 9/11. Under the pretence of destroying weapons of mass destruction, America launched a “pre-emptive” war against Iraq that resulted in the deaths of over 5,000 soldiers, millions of civilians and one dictator. It implanted a proxy government and reduced Iraq to rubble. As artists we had to question: where were these weapons of mass destruction? The company’s response to this line of questioning was to produce my play Truth and Treason, directed by Arianna Bardessono, showing that the “war on terror” was nothing more than a disguise for aggression.

What demonstrated a change in discourse here was the depiction of elements eclipsed by most war-themed plays that offered relatively uncomplicated support for the West-led war, showing soldiers dedicated to peace suffering trauma and disillusionment with patriotism. Some of these plays challenged Canada’s role as a nation of peace and quiet diplomacy. But what was missing in most of them was any representation of Iraqis telling their side of the story in their own voices. What was also missing was the deeper truth. Teesri Duniya filled the void by producing Truth and Treason, which uncovered secrets and scandals hidden in the past and revealed the geo-political powers behind militarized systems of occupation and colonization. Truth and Treason examined the impact war had on the lives of people we did not see on our television screens or stages – Iraqis. In Truth and Treason, Iraqis told their own story instead of having their stories simulated by non-Iraqi characters.

Representation of Iraqi characters brought Iraqi audiences and exiles, enlivening the post-play discussion. Critical and unconventional questions were raised: “Was it a pre-emptive strike or the old itch to fight a new war? Was it a war on terror or the terror of war? Did the U.S. not bankroll the same terrorists, dictators and mercenaries until they turned against them? Can peace be established by militarized means?

There was a genuine two-way communication between Canadian audiences, Iraqi civilians, and exiles, transforming the minds of audiences by listening to voices they had not heard before.

Truth and Treason has been translated into Hindi as Dhokha by Uma Jhunjhunwala and extensively produced in India under the direction of Azhar S Alam.

Commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Armenian genocide, my play State of Denial, directed by Liz Valdez, is a story of two women – an Armenian and a Rwandan – who, while trying to reveal each other’s secret, end up revealing their own. Attention is drawn to hidden identities – what people had to do to survive in order to tell. The play examines Armenian and Rwandan genocides in one paralleling story. In a similar fashion, Counter Offence is a story of conjugal violence in which the struggle to end violence against women intersects with struggles to end racism.

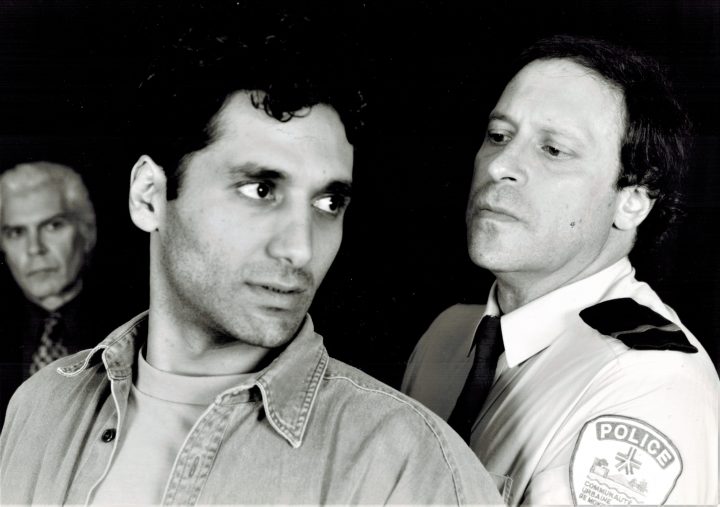

My play Counter Offence, first produced in 1995, directed by Jack Langedijk, changed the political discourse in many ways. First, dramaturgically, it was a play where virtues collided – the struggle to end violence against women came in conflict with the struggle to end racism. Second, in terms of representation and diversity, the characters in the play were South Asian, Iranian, Afro-Canadian, Anglophone and Francophone. A theatre critique commented that it was refreshing to see the metro platform on stage. Counter Offence, like plays by Rana Bose, expresses diversity of cultures in the same story – a major departure from conventional representation by mainstream writers where minority cultures show up every now and then. It is worth noting that representation of diversity came naturally to me and Rana Bose, both visible minority playwrights.

Gendered Discourse

How did Counter Offence change political discourse? In one of the post-play talk-back sessions, an Iranian-Canadian audience member challenged me by saying, “every community beats its women, why are you singling out Iranians?” I responded by saying, “If every community beats its women, why do you feel singled out? This brought laughter and triggered off a lively discussion between Iranian men and women in the audience.

Counter Offence was an imaginary story based on realities. Imaginary stories help reduce sensitivity or shame associated with topics or taboos like conjugal violence. They allow people to express deeply felt personal experiences without feeling exposed. As a result, after the performance of Counter Offence, group-to-group discussions broke out between men and women in the audience, offering an environment for positive transformation. People felt comfortable enough since they did not have to reveal any of their own personal biases during the discussion.

Counter Offence was subsequently translated in French as L’Affaire Farhadi, and in Italian as Il Caso Farhadi. It will be remounted in Montréal at the Segal Centre in March 2020.

Counter Offence was followed by international success with Bhopal, a play about the 1984 Union Carbide pesticide factory explosion that killed or disabled tens of thousands of people in the Indian city of Bhopal. Since its premier (2001), Bhopal has been translated into French, keeping the same title; into Hindi as Zahreeli Hawa, by iconic Indian director Habib Tanvir; and into Punjabi as Khamosh Chiragan di Dastaan.

Other notable productions of changing discourse have been Letters to my Grandma by Anusree Roy; Where the Blood Mixes by Kevin Loring, on residential schools; Corpus by Darrah Teitel, a holocaust story highlighting ethical dilemmas in depicting trauma, family pain and dark history; The Refugee Hotel by Carmen Aguirre, which brings to life the consequences of exile; the French language translation of Where the Blood Mixes, as Là où le Sang se mêle; and Birthmark by Steven Orlov, examining Israeli-Palestinian conflict and youth radicalization in Canada.

Habib Tanvir said, “what I have to say, theatre is the medium.” While artists might lack the economic power to implement changes, they possess the ability to influence feelings and ideas through their performances. Politically engaged theatre is a medium where artists with stories act as activists, to achieve a better world. Politicized performance leads to empowerment of artists and audiences, galvanizing them to resolve problems, and generating lasting impacts.