Norman Bethune was a world-reknowned Canadian surgeon, a passionate humanitarian, and a brilliant medical innovator. Born in Ontario in 1890, Bethune studied medicine in Canada and Britain. In 1925, he contracted tuberculosis, epidemic at that time. He recovered and dedicated himself to help eradicate the deadly disease. He came to Montreal to work at the Royal Victoria Hospital in the research centre. It was the Great Depression, and Bethune became disillusioned with the conservative medical system that privileged the rich over the poor. After a visit to the Soviet Union, where the nonprofit medical system impressed him deeply, he returned to Canada to advocate radical change. In 1936, he volunteered as a doctor during the Spanish Civil War. He devised a mobile transfusion service which allowed medical teams to save soldiers’ lives on the battlefield. Two years later, Bethune felt compelled to go to China and help the Communist guerilla army fight the Japanese invasion. In the most primitive terrain, Bethune’s mobile medical unit treated countless soldiers. At 49 years old, he died of blood poisoning from a cut during an operation. Mao Tse-Tung, whom he had met, honored him in a widely distributed eulogy. Bethune was recognized for his heroic actions and is buried near the Norman Bethune International Peace Hospital in China.

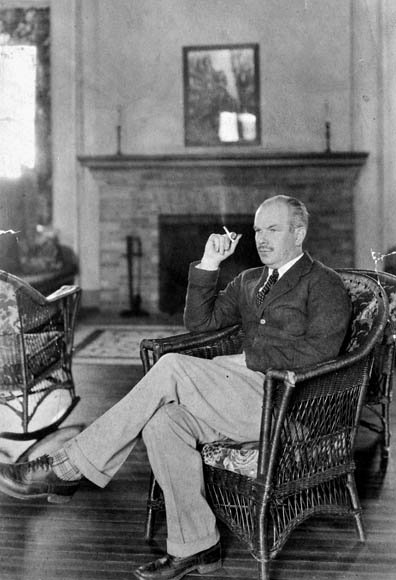

Norman Bethune, 1928, Montreal - "In 1928, Bethune arrived in Montreal, an ambitious young doctor." Credit: Library and Archives Canada

“I do not pity the wounded,

I become the wounded.”

Walt Whitman

Dr. Norman Bethune arrived in Montreal in April 1928 to receive training at the Royal Victoria Hospital under Dr. Edward Archibald, a pioneer at that time in chest (now thoracic) surgery. Dr. Bethune’s first residence was at the Faculty Club of McGill University. He was thirty-eight years old and recently discharged from the Trudeau Sanatorium in Saranac Lake, New York, where he had been under treatment for a severe case of tuberculosis. This contagious disease was epidemic without a known cure. Near suicide, Bethune finally learned of pneumothorax, an experimental procedure which Dr. Bethune underwent. His lungs returned to health and his desire to live also.

He no longer wanted to be a general practitioner but a specialist. He wrote to Dr. Edward Archibald who headed a tubercular research center at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal.

He immediately hired Dr. Bethune to work for him.

1221 St. Marc Street - "Bethune lived four tumultuous years with his wife Frances at this address (building now a highrise)" Credit: Anne Cimon

Dr. Bethune moved to a more permanent address at 1221 St. Marc Street at the corner of Baile street, now part of what is called the Shaughnessey Village. The building has been torn down and replaced by a plain looking highrise. The other buildings would be the ones that Dr. Bethune laid eyes on as he stepped out to go to work at the hospital after a breakfast of “coffee, toast and marmalade.” A late 1800’s mansion across narrow Baile Street, for example. He enjoyed the twenty minute walk to the Royal Victoria Hospital along Sherbrooke Street West.

The hospital at the top of Mount Royal had been built in 1893 in the style of a Scottish castle. No doubt, it reminded Bethune of his ex-wife Frances Penney who had returned to her native Scotland when he fell ill with tuberculosis.The true story of why they first divorced is not known though one version is that Bethune refused to enter the Trudeau Sanatorium unless Frances returned to her family. Now that he had escaped death, Bethune wrote long charming letters to Frances whom he often said he fell in love with “at first sound” due to her Scottish accent. She agreed to come to Montreal and they were remarried on November 11, 1929. That a young woman from a privileged family would be willing to live in such a modest home

as the apartment on St. Marc Street testifies to her true love for Bethune, who signed his letters “Beth,” his nickname with friends.

It was the Depression years, and Dr. Bethune tended to the many poor as he had done in Detroit, Michigan, where he had his first practice and where the couple had first lived. It was there that he contracted TB. Dr. Bethune noticed how the poor died in far greater numbers than the rich and his social conscience deepened in Montreal. Immersed in his work, Dr. Bethune’s surgical skills increased and so did his reputation among his peers. Often irritated by the lack of proper instruments, he invented new ones which were advertised and sold in a prominent American catalogue. The Bethune Rib Shears are still in use today.

He also wrote and published numerous medical articles, and worked as a consultant in hospitals in outlying areas of Montreal such as the Royal Laurentian Sanatorium up north in Ste-Agathe. By then, he had purchased a bright yellow car and cut a dashing figure wearing a French beret and a long scarf around his neck.

Sacré-Coeur Hospital - "In 1933, Dr. Bethune became Chief of Pulmonary Surgery at Sacré-Coeur Hospital north of Montreal." Credit: Alexis Hamel de Images Montréal http://www.imtl.org

Dr. Archibald, a conservative man in his mid-fifties, had grown irritated by the flamboyance of his younger colleague and the irritation was mutual. In January 1933, Dr. Bethune accepted with “delight” the prestigious post of “Chef dans le service de Chirurgie Pulmonaire et de Bronchoscopie” at the newly built Hôpital du Sacré-Coeur run by the Sisters of Providence in Cartierville. This was a French-Canadian Catholic hospital ten miles north of the city and Dr. Bethune could easily drive the distance in his yellow car. The nuns overlooked his bohemian way of dressing (he wore sandals with no socks) and his loud ebullience since they approved of him as a brilliant surgeon who was devoted to his patients. He would often be seen on the ward late at night to double-check on a patient he was concerned about, before driving home downtown.

1947 Baile Street - "Divorced, Bethune hosted here many soirées for Montreal writers, artists, political activists and medical colleagues." Credit: Anne Cimon

Dr. Bethune moved to 1947 Baile Street, a few doors down from the flat on St. Marc Street that he had shared with Frances. Disillusioned by his eccentricities, desiring a normal life, Frances had asked for a second divorce in March 1933, so she could marry A.R.E. Coleman, one of Dr. Bethune’s friends. Though he was devastated by the failure of the marriage, he agreed to the divorce, and even attended their wedding.

His new apartment was on the second floor of an attractive greystone building with a peaked roof, which now fronts the Canadian Center for Architecture. He shared it for a time witha colleague, Dr. Aubrey Geddes. The two single men liked to throw parties which were popular with artists, writers, and political activists. Dr. Bethune often purchased original art to decorate his apartment and support the Montreal artists. He befriended Fritz Brantner who did a painting of the doctor as he attended a patient in the operating room at Sacré-Coeur Hospital, surrounded by the nuns. This painting is widely reproduced in books.

Bethune always wanted to care for the poor. After some deliberation, he decided to attend the International Physiological Congress in Leningrad, Soviet Union. He saw first-hand how the Soviet medical system had reduced tuberculosis by fifty percent and how the poor were attended to as their right. Bethune sold his yellow car to fund this two-month trip which proved to be transformational. When he returned to Montreal, he knew that radical change was needed in Canada’s medical system. He gave an electrifying lecture entitled “Take the Private Profit out of Medicine” to the Montreal Medico-Chirurgical Society.

Something more personal ignited Bethune on his way to the Soviet Union. He had met the young Montreal artist Marian Dale Scott on the boat to London, England. She was the wife of F.R. Scott, the well-respected Montreal constitutional lawyer and published poet. They began a correspondence and when Bethune returned to Montreal, Marian Scott visited him on Fort Street where he had relocated.

1255 Fort Street - "Dr. Bethune had a vision for socialized medicine in Quebec and Canada and joined the Communist Party in 1935." Credit: Anne Cimon

The building at 1255 Fort Street is at the corner of Tupper Street. The exterior is plain, reminiscent of a rectangular convent dormitory, with an entrance a few steps below street level. Bethune met Stanley Ryerson, the secretary of the Quebec wing of the Communist Party. In November 1935, Bethune became a member. This had to be kept secret as it was an illegal organization at that time. Bethune knew that his position at the Sacré Coeur Hospital would be compromised if the Catholic nuns learned about this. His own attitude towards being a Communist remained ambiguous. When he did make it public, and confirmed it to the press, he remarked: “They call me a Red. Then if Christianity is a Red, I am also a Red.”

But what was important to Bethune was to eradicate tuberculosis and treat those who had no means. He held a free clinic at the YMCA on Gordon Street in Verdun. He continued to publish medical articles. In his private hours, he read poetry by William Blake and Walt Whitman, and wrote poetry that he shared with Marian Scott. He also painted a self-portrait that he gave to her as a gift.

Early in the year 1936, Dr. Bethune moved to 1154 Beaver Hall Square near Dorchester Street (now Boulevard René Lévesque.) The building has been demolished but the area he had chosen was popular with artists who had studios. This was probably the reason Bethune moved there. With the help of Fritz Brantner and Marian Scott, he opened the Montreal Children’s Creative Art Centre which was held in his apartment. The children who came on Saturday morning were from the poor families that Dr. Bethune attended to. He wanted to give them a chance to enjoy learning about art .

What really consumed Dr. Bethune that year was a vision for socialized medicine in Quebec and Canada. He inspired like-minded doctors, nurses, social workers and teachers, to form the Montreal Group for the Security of the People’s Health and their manifesto was presented to the public and the new Liberal Premier Adélard Godbout in August 1936. What disillusioned Dr. Bethune was not hostility to the proposal but the indifference. His relationship with Marian Scott, whom he was in love with, also disapointed him as it didn’t evolve beyond a friendship.

He was ready to make a radical change in his own life. He decided to go to Spain to fight the Fascists and offer his medical expertise on the battlefield. As a young man, he had joined the Ambulance Medical Corps in 1914 and had returned home from France with a shrapnel injury to his leg. In 1917, he had enlisted in the Royal Navy as a Surgeon-Lieutenant and served on an aircraft carrier for fourteen months.

A few weeks before his departure, he was invited to speak at Macdonald College in Ste Anne de Bellevue by Irving Layton, a young student with socialist sympathies who had started a series of lectures. Layton, who later became the outspoken world-reknowned Canadian poet, recorded in his memoir Waiting for the Messiah his encounter with Norman Bethune:

“My first impression of Dr. Bethune was of a very intense man, nervous to the point of irritability. He was wearing a drab grey suit, nothing that would make one look twice….Though gaunt, his body exuded a tremendous dynamism, surprising his audience. What impressed me the most was the intentness of his gaze, the forceful conviction behind his words. Here was a man who seemed devoured by an idea, an obsession….”

In his “drab grey suit,” Dr. Bethune was no longer the bohemian surgeon but a doctor on a humanitarian mission to save lives which would lead him beyond Spain to his destiny in China. There, in a remote village, on November 12, 1939, he would die from blood poisoning after a cut in a finger became infected while he operated on a soldier. He was forty- nine years old.

Norman Bethune Monument - "Norman Bethune is honoured in downtown Montreal by this statue in a newly-designed public square." Credit: Alexis Hamel de Images Montréal http://www.imtl.org

At the Hôpital du Sacré-Coeur, a medical library has been named la bibliothèque Norman Bethune. Not far from where he lived in the Shaughnessey Village, there is a Bethune Street in the City of Westmount.

The most important memorial is the newly-designed Place Norman-Bethune, a public square at the corner of De Maisonneuve Boulevard and Guy Street. There stands the statue of Norman Bethune on a pedestal, a gift to the city of Montreal from the People’s Republic of China .