Introduction

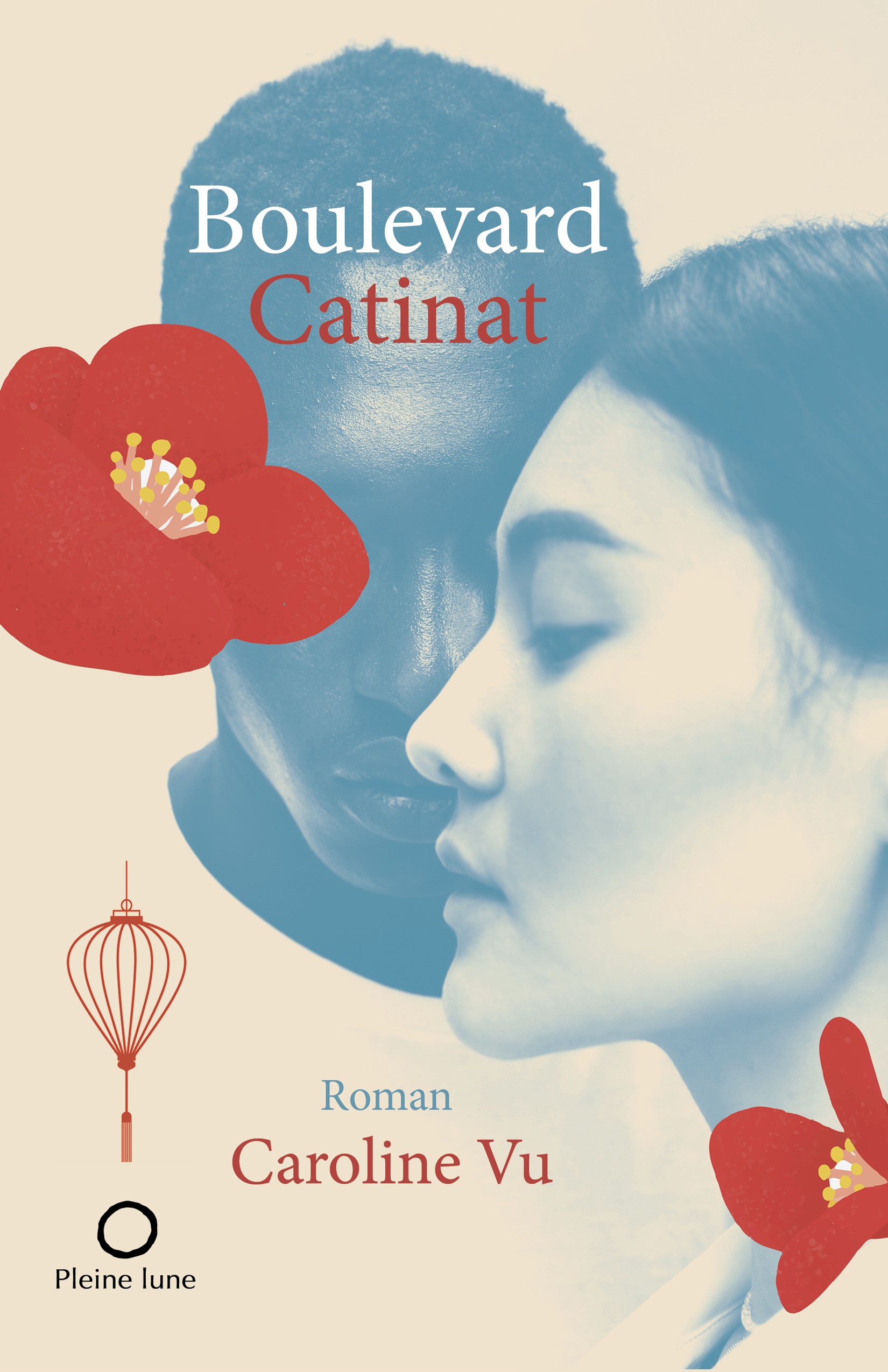

Caroline Vu is a writer and medical doctor living in Montréal, whose writing returns again and again to the country of her birth. Her third novel, Catinat Boulevard, about a war orphan in Saigon and his Vietnamese mother and African-American G.I. father, is being released this fall in English and in French translation. This interview began as a conversation and took form in an exchange of emails. It has been lightly edited for publication.

Joseph Kary: You left Vietnam before you entered into your teens, and that loss of home and place seems to be a constant in your fiction: your own memories of Saigon, then making sense of the images of the war you saw on television from this side of the world. How does art and writing serve to cope with or transform loss?

Caroline Vu: When I left Vietnam with my mother and brothers, I had no idea when I would return. The country was at war. We felt lucky to leave all that behind. In my mother’s mind, there was no question of ever coming back. The pages had been turned, the door to the past closed. In North America, my yearning for home became a nostalgia for childhood innocence. Writing helped me recreate some of that lost innocence. Many of my stories are told from the point of view of a child. When my young characters talk, I re-experience the goodness of childhood. And it is a nice feeling!

Each one of your books has a place name in its title. Yet, if you look on a street map of Saigon today, there is no Catinat Boulevard. Where does your title, and that name, come from?

Catinat has changed name twice. The original street was called Rue Catinat during the French colonial years. The street was renamed Tu Do (Freedom) during the 1960s but for many, it still stayed Catinat. The French name gave the street an aura of class not found elsewhere in Saigon. After the communist takeover in 1975, it became Dong Khoi (General Uprising) Street. Catinat was a street in reality. In my novel, I’ve upgraded it to a boulevard.

You are right, all three of my novels have place names in the title (Palawan Story, That Summer in Provincetown and Catinat Boulevard). This probably has to do with my rootlessness and the need to secure a fixed location.

The title suggests, then, a specific time as well as a place. Did you visit the street? What memories do you have of it?

Yes, I loved strolling with my mother on Catinat. The street was lined with ice cream parlours, restaurants, shops, fancy grocery stores. I remember the much-welcomed air conditioning of those stores. We would go there to buy French butter. Imagine butter imported all the way from France! And during a time of war on top of it! It was an outrageous excess. My mother, like many others at the time, needed this symbol of excess. She felt she deserved it after long hours at the hospital. She was a doctor trying to find “normalcy” within the chaos.

One fascinating aspect of your book is seeing American and Western culture through Vietnamese eyes, learning about America through 1960s television shows like “Mister Ed” the talking horse, through “Green Acres,” through “Mission Impossible.” How did shows like that come to be played in Saigon?

There were only two television channels in the Saigon of the sixties: a Vietnamese channel and an American channel. The American channel catered to American GIs, English speaking journalists/reporters and diplomats. Thanks to the American channel, we had access to typical American shows such as “Bonanza,” “Bewitched,” “The Flying Nun,” “Mission Impossible,” etc. I remember our whole family sitting around the TV watching those shows. Everything was in English. We didn’t understand much but still we watched. We were fascinated with Sally Field flying in the air!

What was it like seeing American soldiers on the street in Saigon as a child?

I never had any bad experiences with American soldiers. They were mostly friendly, giving me a smile or a wave. I suppose my clean clothes helped. Perhaps they wouldn’t have been so friendly if I looked like a beggar. Perhaps they’d have shooed me away. You know, the Vietnamese channel on TV was full of propaganda. Indirectly, we were told to trust the Americans instead of our countrymen from the North. We were brainwashed into admiring these tall foreigners. So, seeing the GIs on the street was always exciting for me.

What kind of education did you have in Vietnam? What kind of school did you go to, who were your teachers, what was the language of instruction?

My mother sent me to a private Catholic school run by very severe nuns. We are not Christians. My grandmother was a devout Buddhist while the rest of the family tended toward atheism. My mother just wanted me on the “right” path with a good and strict education. Language of education? Vietnamese and French. I’d say 65% Vietnamese and 35% French.

It used to be the opposite a few years earlier. The French did a very good job at instilling their culture in their colonies. Vietnam was no exception. The upper-middle class blindly admired all aspect of French culture. From Johnny Hallyday to Brigitte Bardot. My uncles followed them all in Paris Match magazine. Our house was full of French books. I grew up reading Tintin, Asterix, Martine, La Comtesse de Ségur… No Vietnamese books. A teacher once asked me in front of the class if I were Chinese. When I answered “No,” she clicked her tongue. “Why is your Vietnamese writing so bad then?” That question came with a whack on my hands.

Did you maintain contact with your childhood friends after you came to North America, do you know anything about what happened to them?

Up ’til April 1975, I exchanged letters on a regular basis with a Vietnamese friend. If you followed the news, you’d know that the war ended on April 30, 1975 with a communist takeover. Many panicky Vietnamese left on rickety boats and ended up in refugee camps all over Southeast Asia. Others climbed the American Embassy wall for a chance to board helicopters waiting on its rooftop.

It is a scene we have seen in movies and on the news. With the phone service cut off, it was impossible to reach my friend and extended family back home. Months later, when the postal service resumed, we were able to contact my grandmother and aunts. But not my friend. She never answered my letters. For years I imagined her in a refugee camp, then resettled somewhere in Europe, Canada or the US. Through Facebook I was able to track down an old acquaintance last year. She told me my former best friend drowned decades ago. She was one of the boat people on an overcrowded vessel on her way to Malaysia. Her father survived, she did not. The news shocked me. It is also shocking to see that scenario still happening in the Mediterranean.

How did your work on Catinat Boulevard begin? What was the germ of the plot?

In 2017 I wrote a short story about an orphaned baby left hanging all day in a plastic bag. It went on to become a finalist for the Bristol Short Story Prize. I wrote something similar for the Octobre le mois des mots literary competition (La migration). It won first prize in 2020. Somehow, I became obsessed with the image of an unwanted child in a plastic bag hung on a doorknob. That kid wouldn’t let me sleep in peace! I knew I had to tell his story. So, I reworked and expanded the original tale. The end product is a 400+ page novel!

How did you make the leap to being a novelist in the first place? What was the germ of your first novel?

I probably wrote my first “novel” at 11! I had just left Vietnam with my mother and brothers. It was 1970. The war was still going strong. We ended up in a small Connecticut town. We were the only Asian family there. I spoke very little English, had no friends, and was bullied in school. Even my homeroom teacher gave me dirty looks. Looks that said clearly and loudly: “Why is your father not fighting your own dirty war? Why does my brother have to fight for you?” OK, maybe I was paranoid! As a working single parent, my doctor mother had no time for my problems. So I entertained myself by writing stories, happy stories. It was therapeutic.

Going through my junk in the basement, I found those old stories last month. I smiled as I re-read them. The happy naïve stories of a lonely young girl. I had to laugh at my wild imagination.

In my 40s, I worked as a doctor in an immigrant clinic. We had patients from Rwanda, Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam, Haiti, etc. Many were refugees escaping war zones. Although from different parts of the world, their tales of hardship shared a common thread. My patients’ stories moved me. Their real-life dramas inspired my first novel Palawan Story (Deux Voiliers Publishing, 2014). That novel went on to win the Canadian Authors Association’s Fred Kerner Prize in 2015. It was also shortlisted for the Quebec Writer’s Federation’s Concordia University First Book Prize. The prizes opened a few doors. And I began to write more seriously. It was not easy splitting my time between the medical clinic, my computer, two teenaged daughters and my ailing elderly mother. Somehow, I managed!

Your first two books were written from the point of view of a woman very much like yourself. The new book takes a leap, writing from the viewpoint of multiple characters, mostly male, including an American soldier of mixed white and African-American heritage. Did this come easily to you, did you have any trepidation about stepping into another gender, other ethnicities or races?

Taking the voice of a young man was not hard. I grew up surrounded by men: brothers, cousins, uncles. Writing from the point of view of an African-American was harder. I was afraid of being called out. You know, one of my aunts married an African from Djibouti. I have half Vietnamese-half African cousins. They were rejected by many members of my family. It was sad to see my grandmother kicking her own daughter out the door because she married a black man. Sad to see aunts screaming at each other because of a difference in skin colour. The Vietnamese society of the 60s and 70s was a very racist one. Yet not much has been written about this. We like to portray ourselves as victims of the French, the Americans or the communist regime. We write about our resilience in the face of war and exile. I wanted to go further.

In Catinat Boulevard, I explored race issues because I saw how it tore my family apart. And it would be impossible to do this without having characters from another race. I showed my manuscript to a couple of African-American friends for their feedback. My African cousins and the novelist H. Nigel Thomas had also read an earlier draft. Everyone suggested some minor changes and I followed their advice. I wanted the characters to be as authentic as possible.

Tell us about your next project.

I am very proud to participate in an innovative project called OpéRA de Poche. It is Ana Sokolovic’s brainchild. She is the new Canada Research Chair in Opera Creation. She also teaches music composition at the Université de Montréal. The idea is to make opera democratic, modern and available for download online. We use new technologies such as Augmented Reality. This allows viewers to see the singers from multiple angles. With a smart phone or tablet, viewers could even bring the singers into their living room!

My role is to write a libretto in collaboration with the composer, choreographer, IT specialist and graphic designer. Many of my colleagues are talented doctoral students at the Université de Montréal. Others are recent graduates. It is interesting to work with so many young people!

The opera tells the story of a young refugee girl whose mother drowned on her journey to freedom. It is a very familiar story. Nothing new. The drama is still happening off the coast of Greece and Italy. And we must still tell their story.

The opera will be available for download next spring.