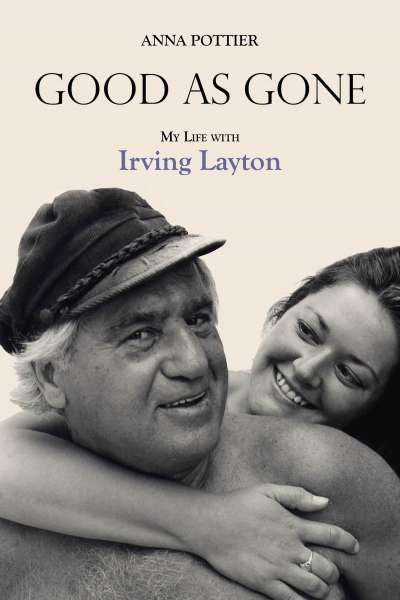

Good as Gone: My Life with Irving Layton, Anna Pottier, Dundurn Press, 2015, 336 pages

In her recently published memoir Good as Gone, about her marriage with internationally renowned Canadian poet, the late Irving Layton, Anna Pottier boldly asserts that “modern Canadian poetry was born in Irving’s living-room” in his “tiny house” on Kildare Road in Montreal where he lived with his third wife, Aviva Layton, in the mid-1950s. This informal gathering of local poets took place every Friday night and Leonard Cohen, then in his early twenties, dropped by. He immediately impressed the well-known Layton with his early poems.

Pottier, in a chapter entitled “The Golden Boy,” describes her meeting with Cohen, a close friend of Layton, on June 7, 1984. She wants to set the record straight on literary myths such as Layton having been Cohen’s mentor. This irritated Layton, she writes, because it was not the truth. And this is what Pottier wants to reveal in her passionate account of the twelve years she shared with Layton, years that she admits have marked her deeply, irrevocably.

Pottier, born in the Acadian village of Belleville, Nova Scotia, dreamed of becoming a writer, not a doctor, as her parents wanted her to be. In 1981, as a twenty one year old student at Halifax’s Dalhousie University, she attended a poetry reading and met Irving Layton who was famous, married, and forty-eight years her senior. They began a correspondence, and when Layton separated from his fourth wife, Harriet Bernstein, two years later, he invited Pottier to move into his Niagara-on-the-Lake home as his housekeeper. She agreed, thrilled that he took an interest in her poems and encouraged her to write.

Pottier began this memoir soon after the death of Irving Layton in January 2006. She defines it as “my homage to and thanks for all that he lavished on me: his absolute trust, an Ivy League education taught at the table, during long walks, and in the pre-dawn light as he challenged me like the extraordinary teacher that he was, all imbued with unconditional love.”

In Good as Gone, Pottier, who now lives in Utah, is remarried, and is a painter in demand in art exhibitions, writes with candour about her relationship with Irving Layton. Since the beginning, she kept personal journals that were very detailed, included verbatim conversations, and notes about Layton’s views on life, death, and the poetic process.

Pottier (her birth name was Annette but Layton preferred to call her Anna, which she agreed to) was as meticulous in her journal keeping as in her work as assistant in preparing the poet’s later books for publication such as his childhood memoir Waiting for the Messiah. Pottier remembers laboriously typing draft after draft on a typewriter, PCs not yet widely in use. Among the interesting selection of rarely seen black and white photos, is one taken by Pottier in May 1985 at their house on Monkland Avenue in the NDG area of Montreal. It is of Layton sitting on the sofa, gazing into the camera, his look bemused and exhausted, the final manuscript pages spread around him on the cushions and coffee table. As she notes in the caption, they had little time to relax as they were bound for Athens.

Some of the best chapters are those that describe the couple’s trips to Italy, a country where Layton’s poetry won deep respect in large part due to the brilliant scholar and translator Alfredo Rizzardi, who promoted Canadian Studies at the University of Bologna. In fact, Italy would nominate Layton’s work twice for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

In an uninhibited voice, Pottier recalls how she accompanied her husband-to-be to the International Festival of Poets, where he had been invited to give readings:

“Landing at Fiumicino, I had to pinch myself. Barely one year earlier, I had come through Rome as a nearly penniless hitchhiker, solitary, hungry, and barely distinguishable from millions of other backpackers. How very, very different for me now, stepping out into the Roman air, warm with oleander, refined perfumes, Marlboro cigarette smoke, and testosterone, on the arm of a poet who was soon to be received like a rock star.”

Pottier also found that Italians accepted their age difference, and this freed her of self-consciousness, being looked upon as the youthful muse of a famous aging poet. One of the happiest of the anecdotes from Italy is in “Lunch with Ettore and Fellini,” when Layton meets and entertains the great filmmaker of 8 1/2, Amarcord, La Dolce Vita, and she finds herself in Fellini’s Mercedes.

Not her family’s rejection, or the complications with Layton’s ex-wives and adult children, could undermine their solid marriage, but their age difference eventually did.

Accompanying Layton on worldwide cultural trips as he aged became traumatic. In 1992, a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease and the beginning of Alzheimer’s, confirmed Pottier’s unspoken fear that she might be incapable to assist her beloved husband as he lost control of body and mind.

With harrowing honesty, Pottier relates how being the caregiver eventually led to burnout. Tears became frequent between the couple rather than the laughter that had bound them. Pottier began an affair with a younger man than herself, and sought the counsel of one of Layton’s lifelong friends, also her friend at the time, Musia Schwartz, who agreed that she should separate and offered to care for Layton.

In Good as Gone, Pottier vividly captures the impersonal cruelty of aging and conveys the love and creativity of their marriage. She writes how she still misses the man and poet who had made so many of her days extraordinary, the memoir a heartfelt testimony to this truth.