** In memory of Alain Resnais recently deceased **

Should the art of cinema be used for propaganda purposes or is it in the nature of any kind of art to remain separated from socio-political issues? We could defend easily either point of view and the question has been debated for over a century in progressive circles.

Marxist theoreticians are adamant and have historically fought against formalism in their own ranks. At the extreme opposite pole, anarchist artists have been staunch defenders of form, creativity, experimentation and the avant-garde. In the middle remain moderate socialists, libertarian socialists and most collectivist and communist anarchists (such as Elisée Reclus and Peter Kropotkin). Some other figures introduced moral and spiritual components (ex. Tolstoy). André Reszler, who examined accurately the topic of aesthetics in relation to anarchism, unfortunately omitted the anarchist artists’ input that is rather formalistic (from Signac to Malevich). An exception in the Marxist field is Lunacharsky who not only wrote about avant-garde art favorably, but tried to reconcile the representatives of Russian humanistic beliefs with the followers of the avant-garde, from 1917 to his death, in the middle of fiery dispute and despite pressures from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU).

This dilemma has been crucial for me when museums and universities entrusted me with the task of organizing festivals of films on anarchism. My first thought went to the precursors: what would C.E.S. Wood have done (to mention but one of them), the founder of the Portland Art Museum? When he was its director, he never hid his anarchist convictions, but, on the other hand, he never took advantage of his position to indulge in propaganda.

Inspired by his example, I devised a choice of films for the Portland, Oregon festivals of anarchism and film that were selected for the quality of their directors (Abuladze, Antonioni, Arrabal, Bolognini, Clément, Chabrol, Cocteau, Comolli, Cuerda, Malle, Montaldo, Olivera, Soderbergh, Zinnemann), all of them known international filmmakers, but only few of them directly associated with anarchism. The choice included some anarchist propaganda films but I balanced them with as many shamelessly anti-anarchist films.

The result was unexpected. We discontented everybody: the anarchist militants who would have preferred we had shown films inviting people to revolution, while the enemies of anarchism were scared by the infamous label and deserted the festivals. But the worst disappointment was caused to us by the local professional critics who boycotted the Portland première of rare films or visits by invited foreign guest speakers.

But it is now time, instead of expressing bitterness, to focus on how French film director Alain Resnais and novelist Jean Cayrol together succeeded in sending a powerful political message cleverly dissimulated inside an avant-garde film that is not easy to decipher.

The two authors had already collaborated on two documentaries: Toute la mémoire du monde (1956, on the French National Library) and Nuit et brouillard (1955, on Nazi concentration camps).

Cayrol, a fervent catholic, had joined the Resistance. Denounced by a traitor, he was arrested and sent to a prisoners’ camp in Germany. He survived and the script of Nuit et brouillard (Night and Fog) narrates what he saw in reality, an experience that Resnais transformed into bitter images.

The German ambassador complained to the French government. It might have happened before with another film on the same subject by the Jewish Polish survivor of the German concentration camps, Dr. Wanda Jakubowska, who, in 1948, launched her Ostatni Etap (The Last Stage) that suddenly disappeared from circulation under specious pretexts.

What struck me, much later, was that Dr. Annette Insdorf, when she was consulting me while researching for her book Indelible Shadows: Film and the Holocaust (1983), indicated that she was not aware of the existence of that gem. That confirmed my suspicions.

It is sad to think that even democratic countries resort to some kind of censorship of “Hot” political events for reasons other than art or reality. There were reconciliation treaties being signed at that time and it was not considered politically correct to be going against the newly formed associations proposing friendship between the two traditionally enemy countries. The French government decided to prohibit the film in France. Thus Night and Fog was shown only abroad and could not be projected in France for many years.

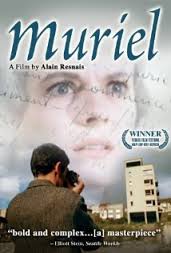

Resnais and Cayrol learned the lesson and with Muriel conceived a film that was so complex that censors could not understand the intentions of the authors. No one noticed, for instance, that there is no character named MURIEL in the cast of characters although this female name is pronounced several times in the course of the film and was frequently a subject of conversation.

But MURIEL was also the title of the 8 mm. documentary that Bernard Aughain, the son in the film of the antiquarian widow, Hélène Aughain (played by Delphine Seyrig, the same actress who had become famous only two years before in another film by the same Alain Resnais, L’année dernière à Marienbad) was shooting and slowly editing, secluded in his apartment, after he has come back from his military service in Algeria. It is never revealed that MURIEL was also the name of an Algerian “résistante” tortured by the French army. The title appears on the screen for split seconds and is rather difficult to perceive by the spectator who does not have sharp sight or does not pay attention to minute details. The name, however, becomes a symbol and a banner representing a cause: it evokes the TORTURE that took place despite the fact that the French government had signed all the international conventions on the treatment of prisoners. Torture was known to be practiced by all dictatorial governments but openly denied by (pseudo?) democratic ones, although they practiced it. And it is unfortunately still practiced at the present time by many of them, unless, that is, they are denounced by Amnesty International.

Later Gillo Pontecorvo, in La bataille d’Alger, raised the issue openly, but he was not living in France and could take an open position against French militarism. The stroke of genius of Cayrol-Resnais was to show that colonialism, oppression and torture can also poison the life of their practitioners. The character Bernard in Muriel is an example of someone who has been soiled with indignity just by obeying orders, like most Nazi criminals judged at Nuremberg (or elsewhere), hiding behind the excuse of obedience to hierarchy. The filmmaker Bernard making the short documentary MURIEL is one of the colonialists whose conscience is affected by recent events. He has been back in France for 8 months and he is still obsessed by the real Muriel. One can sense that she might become a lifetime nightmare, as happened to some Nazis who saw no other escape from their lives except suicide, sometimes even decades after their crimes.

There is the real Algeria but also imaginary Algeria in Muriel. That is true for Alphonse Noyard (the former beau of Bernard’s mother) a despicable but charming character who brags about an invented past of 21 years spent in that country, where we find out, towards the end of the film, he never actually went. In the film, Algeria becomes, for the French, a daily reality that even as an hypothesis is more true than the actual Algeria was.

The final cut of Muriel ou le temps d’un retour is a revolution in technique. In Resnais’ previous films the spectators become used to the slow movement and meanderings of the camera, while in this film we have a rapid succession of first shots that leaves the viewers astounded. Wanderings of the image become wonderings. They look unrelated as in a puzzle game in which the mosaics seem not to belong, creating a senseless dilemma, or inviting the spectator to construct a meaning.

Jean Cayrol, a literary editor, was very familiar with the Nouveau Roman, just as Alain Resnais was an adept of the Nouveau Cinéma .

Joining their talents they create a masterpiece that combines originality and commitment, as is required in a world in crisis, suggesting instead of preaching, inventing ex nihilo in lieu of imitating some previous masters, becoming themselves New Masters, at least for a generation, inevitably destined to be surpassed. Together they show how to create a revolution not by talking about it but by concocting a revolutionary way of doing it, knowing full well that the result was valid only for that particular moment.

Alain Robbe-Grillet in his “manifesto” for a New Novel gives us a very clear outline of this idea: Crystallization is a danger and the only those avant-gardes that will survive and outlive us will be those that have learned the lesson of continuous renewal.