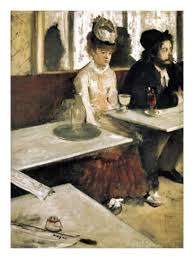

When I wrote a poem inspired by the 1876 painting by Edgar Degas Dans le Café also known as L’Absinthe, I wasn’t aware that I was practicing a genre that originated in ancient Greece. Ekphrasis, from the Greek “ek” — “out” — and “phrasis” “to speak”, is an awkward word to spell, and far less melodious to pronounce than the Greek ekstasis which means “in a trance.” There is no firm definition for ekphrasis but a basic one is “a literary description or commentary on a visual work of art” www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ekphrasis.

Over the centuries, writing ekphrasis has become more flexible concerning which type of art can be included such as sculpture, photography, film, dance…but the original and most common has been poetry. In our own age of multimedia, writers are interested in exploring its possibilities.

In Arc Poetry Annual 2011 dedicated to ekphrasis, Aislin Hunter commented that “…as an act part of what defines ekphrasis is its phenomenology and its effect that is dynamic, that makes and remakes meaning and story, ad infinitum, between the maker and viewer.” That word dynamic suggests the energy and force that this “act” possesses when done well. And certainly there is a quality of “ekstasis” or ecstasy for the writer who practices this “mysterious ritual,” as Robyn Schiff remarks in her essay about Mary Hickman’s prose poems at www.Bostonreview.net/poetry/poets-sampler-0.

My own early experience with this genre began with a visceral reaction to Degas’ masterpiece L’Absinthe. I felt an intense connection to the young French woman slumped dejectedly at the café table. Curious, I did some research about the painting and learned that it depicted the Parisian Café Nouvelle-Athènes that impressionists painters liked to frequent in the mid-1870s. Degas pictured a couple who were friends of his, the actress Ellen Andrée, and the bohemian artist Marcellin Desboutin. Even from the pages of an art book, the power of the painting, which now hangs at the Musée d’Orsay, transcends the reproduction.

I saw in the body language of Ellen, the existential exhaustion that I had often experienced. I imagined the milliner’s hat on her head as a black iron pressing down, she suffered a migraine, her glass of absinthe on the marble table top, untouched except for a teaspoon used as medicine. In fact, I learned that absinthe was a liquor known at that time as “la fée verte” (the green fairy), referring to its tint and quality of inducing hallucinations. Artists of that period such as Vincent Van Gogh and Henri de Toulouse Lautrec were addicts.

In 2009, at the Art Gallery of Ontario, in Toronto, writers were invited to tour the permanent collection and compose poems inspired by the art on display as exercises in ekphrasis. A few months later, a well-attended public reading of the results was held at the AGO. Kelley Aitken, a facilitator of the project, remarked in the Arc Poetry Annual 2011 that “”I don’t think we choose the artworks that move us, I think they choose us. John Berger says that when drawing, artists feel a reciprocal energy with their subject: something is thrown, something is caught. A similar energy, a kind of call-and-response, is always potential in a work of art. And I think the writing of the poem is the honouring and distillation and revisitation of that. Ekphrasis is the gallery of the mind.”

In a Trance

By Anne Cimon

From the painting L’Absinthe by Edgar Degas, 1876

Her presence in the café

is abstract.

She sits at a table,

her glass of liquor

untouched

except for a spoonful,

a medicine

for her menses.

Migrainous, she feels

her hat rest heavy

As an iron

on her head.

She is too weak

to lift it.

Sitting on the bench

beside her,

a stout dark man

turns aside

to smoke his pipe.

He harkens

to the male voices.

In a trance,

she hears sybils speak.

“Ten of the Best : examples of ekphrasis,” an article by John Mullan can be found at

www.theguardian.com/books/2009/nov/14/ten-best-ekphrasis-john-mullan