After years of denouncing Mother Country’s contempt for its emigrants stuck in the 1950s, I am airing the dirty laundry. What makes the immigrants stuck? I do not see peasantry as pejorative, just for some pernicious superstitions passed down through their descendents, who should know better. These examples aren’t representative of all immigrant experience.

We are becoming the men we wanted to marry.

Gloria Steinem (Ms. magazine 1982)

The worker is a slave of capitalist society; the female worker is the slave of that slave.

James Connolly (1915)

A slavish bondage to parents cramps every faculty of the mind.

Mary Wollstonecraft (Vindication of the Rights of a Woman, 1792)

Remember, it’s as easy to marry a rich woman as a poor woman.

William Thackeray

Superstition is the religion of feeble minds.

Edward Burke

With much dismay, regressive forms of feminism re-emerge today. You don’t need a Gender Studies degree to keep a pulse on these matters. It is easy to see what created these fembots. Yesterday’s celebrity role models created a generation of starlets famous for contributing nothing. The sexual revolution brought to us by the media, shows women exposing their bodies for gains however the power structures remain. Southern Europe’s traditional countries of emigration hold contempt for Diasporas as islands of backwardness. Not that these countries are anymore progressive in regards to gender rights. In Italy, snagging that showgirl role opens the door to cinema and naturally, politics. Though these ex-showgirls, or pageant-contestants-cum-politicians, who transitioned from Berlusconi’s Mediaset network into his governments, may dress the part and repeat the lines, but they never get the important ministries. For an inkling of it, see Lorella Zanardo’s documentary, Women’s Bodies. http://www.ilcorpodelledonne.net/?page_id=91

Another trend closer to home: Daughters of immigrants in Canada have this self-imposed pressure (and pressures from above) to get married. This single girl’s dilemma seems cross-national as the plethora of chick lit, chick films and TV shows like Sex In the City that condition us, it must end in marriage for everyone. The Bachelor also showcases the full-blown desperation of women suffering from considerable delusions.

Another trend closer to home: Daughters of immigrants in Canada have this self-imposed pressure (and pressures from above) to get married. This single girl’s dilemma seems cross-national as the plethora of chick lit, chick films and TV shows like Sex In the City that condition us, it must end in marriage for everyone. The Bachelor also showcases the full-blown desperation of women suffering from considerable delusions.

The desperation is so heavy in such immigrant families, that they constantly remind their daughters of their failure to get married and procreating instead of praising their educational achievements. The onus on education is purportedly very important in immigrant families, yet, traditional forces obfuscate. Such fathers would say at the wedding reception, “We thought she’d never get married.” While immigrants are embittered they can never go home again, since it too has changed, their children can never leave home again, thus recreate a parallel “home.” The tyranny of keeping up appearances inherited!

The vulgarity of New Money, always known for being ostentatious for others, the bigger and tackier, makes for a new generation of self-entitled hyphenated ethno-Canadian Princesses. Creating the ripe conditions for Bridezilla behaviours, where a stunted adolescent craving for independence becomes a dream misplaced onto the fabled wedding day.

These girls, who in the past may have not had a chance for higher education because their parents invested in their sons, have had the benefit of some education; something their parents may have scarcely had back home. Children of peasant societies were brought up in the New World that taught them, more or less; they have choices for their future and are allowed to have it all (ambition and family). Through education, these women who came of age in the1960s already trudged the stereotypical route pre-destined for the female as secretaries, bank tellers, nurses and teachers and cleared the way for later generation of professionals, chartered accountants, lawyers and pharmacists. The economic leap from two generations is big: one from Old World pre-industrial to industrial working class (immigrant parents who saved to become comfortably middle class), to the recent super career women who have climbed up the rank.

These girls, who in the past may have not had a chance for higher education because their parents invested in their sons, have had the benefit of some education; something their parents may have scarcely had back home. Children of peasant societies were brought up in the New World that taught them, more or less; they have choices for their future and are allowed to have it all (ambition and family). Through education, these women who came of age in the1960s already trudged the stereotypical route pre-destined for the female as secretaries, bank tellers, nurses and teachers and cleared the way for later generation of professionals, chartered accountants, lawyers and pharmacists. The economic leap from two generations is big: one from Old World pre-industrial to industrial working class (immigrant parents who saved to become comfortably middle class), to the recent super career women who have climbed up the rank.

Yet, there is an appearance of emancipation. In societies, which value traditions and appearances, these new professionals have to broach the past burdens with a new reality and newfound wealth. Their parents repeatedly may have said NO; now money changes everything. They can make things happen in their new position as women of means and say yes to themselves and would be partners as long as it affords them normalcy. Normalcy as long it conforms in the eyes of their brethren and monoculture friends who maintain and reinforce such beliefs.

In peasant societies, women obtained a modicum of power when she left her father’s house for her husband’s. She was supposed to get married very young, bear children and her obligations and duties in her newfound status as matron included keeping the register of money, the children’s welfare and their moral education. She went from working the fields of her father to those of her husband. Procreation meant making more hands to till the soil. If she was the daughter of a somewhat wealthier peasant family who owned their own land, her dowry made her attractive.

In Italy, daughters of Americani, whose fathers who emigrated to the Americas and returned were particularly attractive, and thanks to him, his son-in-laws could emigrate ensuring a win-win situation for the newlyweds; where the man could get a job while the girl got out of the village and their passage to the New World was their honeymoon. Fathers made sure the suitor had some dough of his own. The merchant class married the merchant class and nobility married nobility. This was feudal society in a nutshell. Depending on the family, one had freewill to marry whom they wanted within the class strata. Except for the rare case of the landed aristocracy when fortunes went terribly wrong, where the Nouveau Riches traded huge dowries for respectability as in Tomasi di Lampedusa’s book and Visconti’s film, The Leopard (1963). Post-industrialized society brought freedom from the lands and some traditions went by the wayside.

These structures were dragged to the New World to women who were taught one way, formally by society at large and another at home. The dreaded cliché of culture clash only exists if the children really want to rebel. Fear held peasants submissive, superstition a by-product, that’s why they rarely revolted save for some incidents in history. Children of peasants rarely revolted for the same reason, save for some of course.

When a bride shouts at her wedding party, “Girls, I finally can go out now!” because her parents kept her on a short leash; marriage means illusory independence. While most of us were at university, one girl was getting married at 20 “because there’s nothing to do.” A long mane girl in her early twenties can’t cut her hair, “What if I get married this year?” Oh, it’s derisible all right if it weren’t so terribly sad.

Greek superstitions like not telling anyone about a pregnancy until after 5 months, or the baby’s sex, or not buying a gift for the baby because it might jinx the pregnancy. Likewise, after the birth, mother and the newborn are not allowed to leave the household or welcome any well-wishers for 40 days (a common recurrence in Christianity, even repeated for funeral memorials in the Greek Orthodox faith). Forty days indoors without accepting visitors because they bring in “viruses” (modern speak for the evil eye because well-wishers may be jealous and cast negative thoughts onto the innocent newborn). These beliefs are sadder still when it comes from women born in Canada and university-educated in scientific fields. Changing of the rules oblige in the New World, exceptions like hospital visits (apparently, hospital rooms are virus-free sanctuaries) and the mother can leave the house for pediatrician visits for weigh-ins. Even for neo-subscribers of superstition, there is a logic that deems it necessary to adapt and accept the necessary medical visits.

Of course, they’ve picked up foreign traditions like North American eating habits, showers and bachelorette parties while not adopting others like moving out before one marries. Preserving some old school traditions like exploit-a-grandmother free daycare when the couple can afford it, or is it New World opportunistic, individualistic thriftiness while forgoing Old World generosity they’ve come to expect from their parents?

Not all archaic Greek superstitions like the trick marriage have been replicated in Canada, thankfully; posing next to a desired woman dancing unbeknownst to her and using the photograph against her will or the taking of a woman to a Greek island and the boatman strands her overnight to compromise her honour. These schemes resulted in marriages, albeit unhappy ones. And this was Europe in the 1970s at the same time Switzerland finally let women vote.

These exceptions in the New World reminds us of when mythology morphed into organized religions in the Byzantine and Roman World or where Post-Colonial Contact and slavery paralleled those of organized religions creating syncretic religions. Within one family’s immigration trajectory, tradition and mores morphed and adapted to the country of adoption. The newer generation pick and choose what will remain as tradition and what isn’t convenient anymore. They no longer have a talent for the kitchen, which was once praised as an ideal trait for a woman to have, but continue on the road of feminine self-sacrifice. Another inane belief is that the second daughter cannot marry if the eldest daughter is not married. In the past, first generation adult children of immigrants gave away their paychecks to parents. In such contexts, children felt the burden of maintaining a household, duplicating the structure back home where the son emigrated elsewhere and had to support the family; the novelty was the guilt-ridden resentment from not living your life. It was payback time after years of parents paying for their education. The majority of ethnic parents usually coddle their adult children.

Many in the West cast their disapproval or out rightly disparage cultures where arranged marriages (now gone hi-tech with internet matchmakers) and honour killings occur. Case in point: When Montreal Afghani parents, with the help of their son, orchestrated the Kingston drowning deaths of their daughters and wife number one who was barren and relegated to nanny/aunt status. All because they feared their 19-year-old daughter wanted to marry a poor Pakistani! The murders only created the opposite: the remaining living daughters who were taken by children’s services will grow up in Quebecois foster families.

And you hear about setting aflame saris, disobeying the family decreed marrying aged Uncle they chose for her. The Punjabi girl from B.C., married whom she wanted to, in spite of all the machinations, was murdered by family members with a phone call to India. The fear of the daughter becoming too Western, the West, where they chose to immigrate for its standard of living, yet traditional parents can’t control the floodgates of assimilation.

We forget Western Culture also fraught with the same contradictions and experiences. For honour killings, one needs to look at the films of Pietro Germi, who as a Northern Genoan seems to have a fetish for Sicilian nobility and mores, which weren’t even practiced by peasants in continental Italy.

In Divorce Italian Style (1961), he skewers Italy which only introduced divorce in 1974, where nobleman Fernando Cefalù (Marcello Mastroainni), nicknamed Fefe by his overbearing mustachioed wife, takes a liking to his young cousin Angela. Since divorce was non-existent, he was inspired by a news event where a cuckold wife used the honour-killing clause in ancient Sicilian canons as a defence for her husband’s murder. To get a light sentence, he had to set up the conditions to entrap his faithful wife even if it renders him cuckold in front of glares and gawks of a machoistic village. More witnesses, the better where time-honoured la bella figura (keeping up appearances) is paramount to laws and even supersedes them. Respectable women of all classes weren’t allowed to enter bars or dance so we witness men dancing with men at the Communist Hall. When a Northern Communist leader comes to give a travailed speech about the emancipation of women and mentions that recent case of honour killing at the comizio, the men in the front row shout in Sicilian, “Buttana!”(Puttana / Slut)

In Divorce Italian Style (1961), he skewers Italy which only introduced divorce in 1974, where nobleman Fernando Cefalù (Marcello Mastroainni), nicknamed Fefe by his overbearing mustachioed wife, takes a liking to his young cousin Angela. Since divorce was non-existent, he was inspired by a news event where a cuckold wife used the honour-killing clause in ancient Sicilian canons as a defence for her husband’s murder. To get a light sentence, he had to set up the conditions to entrap his faithful wife even if it renders him cuckold in front of glares and gawks of a machoistic village. More witnesses, the better where time-honoured la bella figura (keeping up appearances) is paramount to laws and even supersedes them. Respectable women of all classes weren’t allowed to enter bars or dance so we witness men dancing with men at the Communist Hall. When a Northern Communist leader comes to give a travailed speech about the emancipation of women and mentions that recent case of honour killing at the comizio, the men in the front row shout in Sicilian, “Buttana!”(Puttana / Slut)

Germi’s other Sicilian comedy is more tragicomic. In Seduced and Abandoned (1964), a very acerbic script by commedia all’italiana ace AGE, Agnese (Stefania Sandrelli) is raped by her sister’s fiancé Peppino. She is further victimized: her name alludes to Agnes Dei, a sacrificial lamb. After doing some rudimentary penitence (sleeping with rocks in her bed) and hiding the rape from her sister Matilde, she writes it down, tears it up only for her mother finding the bit she “succumbed to lust.” She undergoes the “virginity test” which the father prescribes to the rest of his daughters for good measure, and banishes her in a room where the only way to communicate is via furnace pipes.

Germi’s other Sicilian comedy is more tragicomic. In Seduced and Abandoned (1964), a very acerbic script by commedia all’italiana ace AGE, Agnese (Stefania Sandrelli) is raped by her sister’s fiancé Peppino. She is further victimized: her name alludes to Agnes Dei, a sacrificial lamb. After doing some rudimentary penitence (sleeping with rocks in her bed) and hiding the rape from her sister Matilde, she writes it down, tears it up only for her mother finding the bit she “succumbed to lust.” She undergoes the “virginity test” which the father prescribes to the rest of his daughters for good measure, and banishes her in a room where the only way to communicate is via furnace pipes.

The father’s motivation isn’t the welfare of his daughter. Marriage can cancel Peppino’s crime with a matrimonio riparatore (shotgun marriage) only codified in Sicilian legal canon but that would explicitly mean the girl has been dishonoured. And he cannot resort to honour killing defence since time has lapsed from when he just heard about it. His nightmares are grotesque renderings of “WHAT WILL PEOPLE THINK” if the daughter’s rape and crime, if denounced, are exposed. Given a beating and ultimatum, Peppino refuses to give up his law studies and is convinced by his mother that he cannot marry a dishonoured woman even if he was the one who raped her.

Agnese tries to prevent the honour killing plot by escaping to the police but remains evasive when the police chief asks whether there’s a plan or not, to finally say no. The police chief tells the dimwitted carabiniere from the North who believes her at face value: “In Sicily, yes is no and no is yes. We’re not in Treviso anymore.”

When Agnese is forced into marriage to cancel Peppino’s crime with a matrimonio riparatore, the sensible official asks if she freely wants to marry him. She screams hysterically “YES! YES!” and bursts into tears. In the great montage where Peppino reveals his doctored version, she takes on male behaviours, smokes and seduces, he remains a hapless victim aggressively attacked by a promiscuous woman.

The father, who puts the Padre in Patriarchy, transforms and manipulates his all-consuming fear into devising mise en scenes, so Peppino can be accepted socially since people would talk if it were revealed to be a matrimonio riparatore. But that causes another hypothetical dilemma: will villagers ask, “Wasn’t Matilde engaged to Peppino?” He has to find another suitor for Matilde, a destitute and suicidal Baron, and buys him false dental implants. He orchestrates a serenade from Peppino for Agnese, fakes a refusal complete with gunshots into the sky so everyone can hear. The father’s bravado after some villagers enquire about the reconfigured Matilde – Peppino – Agnese love triangle: “We’re not in the Middle Ages anymore!” This, after a well-thought out recreation of the rape via a public kidnapping to hide Agnese’s pregnancy during the Saint Liboria procession in the town’s square in which everyone could witness.

The police chief has a nose what to expect since he drives out of town that day in order to not witness the faux kidnapping spectacle, exclaiming “What a town!” as he covers his hand over the island on the map of Italy, “much better” wishing an atomic bomb would hit his island.

The attempt to trial Peppino ultimately unveils the truth creating the ire of townspersons towards the family. Even the Baron, throws away the dental implants saying he cannot be bought into marrying Matilde who comes from a dishonourable family. Matilde becomes a nun and Peppino and Agnese are promised to one another at the father’s deathbed, a wish that must be carried fully.

Not that these beliefs still exist today in Sicily. Some practices that have died in the mythical Village of provenance, some benign and silly ones like the serenades were transposed by emigrants.

Sicily is the land of creative writers, who’ve mediated on its complicated moral codes and contradictions. Like Vitaliano Brancati’s novel (and a Mauro Bolognini film; script by Pasolini) Bell’Antonio (1960) is about a sought-after handsome nobleman, Antonio who comes from a family of ladies men and turns out to be impotent in a macho society where aristocrats have lost currency and now need to marry New Moneyed women. In Bell’Antonio, it is an arranged marriage out of class preservation that evolves into love. This time, the family honour is dependent on the male and since Antonio cannot consummate his marriage to saintly beautiful Barbara (Claudia Cardinale), it is annulled. Antonio (Mastroainni) gets it on with prostitutes and honour is finally restored when his servant becomes pregnant to the delight of his mother who doesn’t care whether or not the child is his or not. Even if he has to marry beneath him, class is no longer important.

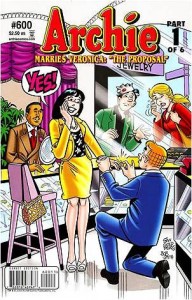

Male gold diggers preying on rich women are nothing new even in the pubescent world of comics: unemployed Archie chooses Veronica over Betty at first. Consumerism made everything possible, buying happiness or love is a new subterfuge for a mercantile exchange for marriage where the individuals are willing or unwittingly impervious participants. The latter usually love-blind with a disregard for verbal abuse because she exudes neediness. Peasant dowries (or the bride’s side paying for the entire wedding in its modern face, common in Anglo weddings) were replaced with professional women buying their own wedding rings, homes and nice toys their non-professional husbands ask for: cars, the latest electronic device. The problem arises when the unequal entities are confronted with the crux of all inequalities: WHO DECIDES? Merely making more money than the man not only ensures bread-making status, it can emasculate the traditional husband who is left in the peculiar old-new position of making the decisions with his wifey’s money as the Kept Man.