This was my third time at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). It was also Piers Handling’s final year as the TIFF director, with Joana Vicente now as its new director – a sign of the times reflected by a woman at the helm of the festival. TIFF’s mandate this year was to re-address gender disparity at film festivals with the Share Her Journey rally and the #TimesUp movement demanding more representation from directors and critics. An invitation was extended to black or queer female critics with the aim of seeing film through their optics since male and pale critics make up 30% of the industry, as do white female critics, while minority male and female critics make up 20% each. Apparently TIFF outreached to 20% of global critics.

Claire Denis premiered her new sci-fi High Life at TIFF, as did Canadian Patricia Rozema with Mouthpiece and Nicole Holofcener with her Netflix release, The Land of Steady Habits, while Nadine Labaki’s Capernaum premiered at Cannes. A CTV reporter asked people waiting in queues if representation was important to viewers. I realized that I was only seeing one film directed by a woman because it just happened to be that way – hardly a ringing endorsement of women in cinema and only slightly better than my CanCon roster. TIFF’s World Cinema section represented women as well, from Bai Xue (China) to female directors from India, including Rima Das with her film Balbul Can Sing.

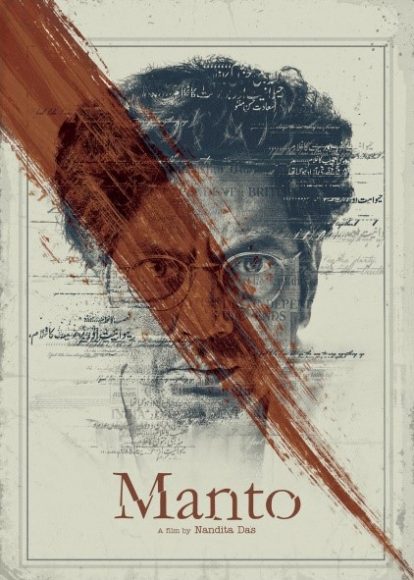

While Nandita Das’s Manto premiered at Cannes, it was her male compatriot Vasan Bala’s The Man Who Feels No Pain that won TIFF’s Midnight Madness People’s Choice. When it counts, women are denied the Platform and People’s Choice Awards. The FIPRESCI (Fédération Internationale de la Presse Cinématographique) International Critics jury’s Discovery Award went to Irish Carmel Winters’ Float Like a Butterfly, about a female boxing Traveller who worships Muhammad Ali. Laura Lucchetti’s Flower Twin, about an African migrant in Sardinia, got an honourable mention.

The Best World or Asian film Premiere Award was given to Vietnamese Ash Mayfair’s The Third Wife, while the Eurimages Audentia Award for best female director went to Ethiopian-Israeli Aälam-Warque Davidian’s Fig Tree. Montréal based Katherine Jerkovic’s Roads in February won the best first Canadian Feature Film Award, while the best Canadian Short Award went to Meryam Joobeur’s Brotherhood, about Tunisians in Québec.

COLD WAR

Pawel Pawlikowski’s much anticipated film, Cold War, is inspired by his parents’ laborious and tumultuous love story defying borders and all reason. Like Ida (2013), which examines Poland’s complicated complicity in the Holocaust through the eyes of a novitiate nun, it is shot in chiaroscuro black and white with music taking on a prominent role. After Liberation, Poland wants to reveal its national pride in the People by bridging nationalism and populism with Communism amidst the 1949 land reforms. Cold War begins with an Alan Lomax-type ethnomusicology segment, with the Party’s cultural representative and music directors searching for undiscovered talents in the Polish countryside. Lech Kasmarek, the chauffeur/apparatchik is lamenting that an ethno-linguistic minority’s folk song can’t be in it because it’s “too bad Lemko isn’t our language.” Poland Has Talent-like auditions at a former manor where “all this is yours,” provided the individuals are well versed in Polish folkloric song and can dance to “the music of your grandparents against imperialism” or on songs like “I won’t marry a master.” This is in preparation for a Youth Festival in Berlin.

Crafty and ambitious Susana, henceforth Zula for short, convinces a peasant girl, Leda with the pure voice, to audition for a duet that masks her vocal limitations. Wiktor, the pianist/choral/music director, prefers her charms, while the female judge has her all figured out since she is an ex-convict. Zula is sent to prison for the attempted murder of her father who, after a night of drinking, “mistook me for my mother and I showed him the difference with a knife.” Suffice it to say that Wiktor, who looks like a French New Wave character – a Belmondo minus the broken nose, more closely resembling François Truffaut – is smitten, and he and Zula automatically embark on a relationship, frolicking in the fields. At the first lovers’ quarrel, she jumps into the river. One can mistake Zula’s personality disorder for the dramatic exuberance of a temperamental artist.

Yugoslavia, 1955, at the Partia Narod, Wiktor follows the Polish Troupe’s tour playing Mazurkas and a Serbian folk song about a silk thread. Zula eyes him in the audience. Yugoslav police arrests Wiktor during intermission despite his having a visa. A policeman adds, “Warsaw is the Paris of the East,” as he is sent on the train. Luckily, this time it isn’t the Trans-Siberian Express.

By 1957, in Paris, Wiktor is working on the soundtrack of an Italian film depicting a murder. Zula finally reaches Paris, married to a Sicilian to get her out of Poland. She says, “It wasn’t in church so it doesn’t count. The main thing, you’re not married.” The scenes near canals look like a nod to Luchino Visconti’s White Nights; instead of St-Petersburg, Seine by night with lovers in alcoves. Back in the jazz club where Wiktor plays piano and watches Zula’s frenzied rock n’ rolling dancing, the handheld camera pays a dizzy musical tribute to Tony Richardson’s Look Back in Anger’s dance scene.

The sequence represents the Western side of the Cold World divide. Bill Haley and his Comets “Rock around the Clock” while Zula is passed around male partners under Wiktor’s impassive eye. When she falls off the bar counter, she tells Wiktor, “In Poland you were a man.” The club’s name, L’Éclipse, and Zula’s blonde hair resembling Monica Vitti’s mane, seem like deliberate signifiers, harkening the ennui of Michelangelo Antonioni. At the end of the evening, a sedate Zula singing in Polish, “Dark Eyes, you cry” (not the spirited Russian “Dark Eyes/Ochi Chernye”) shows she is more comfortable on the other side of Europe.

The abyss in culture between the lovers and the gulf between them widens at the party. Zula drinks and flirts with Michel, Wiktor’s colleague at the film dubbing company. Back in Poland, 1959, an unglamorous, kerchiefed Zula is on a train bound to a snowy village to visit imprisoned Wiktor. This time it is Zula who promises she will wait for him.

At Warsaw’s Lato z Pisenka, Song of Summer Extravaganza of 1964, we see a brunette-wigged Zula singing a tropical Baio Bongo number with bandmates donning Mexican hats, depicting how her career has drifted into mainstream cabaret.

Finally, Zula takes Wiktor back to the countryside where they met, to the abandoned bombed-out church with no cupola, to marry without a priest but by solemn candle, where Wiktor, with his atrophied finger (acquired while in the Gulag), tries to exchange vows. Soon thereafter, Zula wants to see the view from the other side. The film makes the Cold War the periphery, the context where the metaphor is the pendulum – through time or geo-politics – shifting the yo-yoing relationship itself. Curiously enough, Pawlikowski’s parents died before Glasnost.

CAMPY THRILLER

Greta is Neil Jordan’s offering, starring the legendary Isabelle Huppert and Chloë Grace Moretz. Described as a psychological thriller, it playfully situates itself somewhere between camp and comedy. From a Ray Wright play, the tone takes an eerie turn when Huppert answers the door to an ingénue delivering the purse she had lost on the Manhattan subway. That is when I realize that Isabelle’s acting was different. This film is similar to Get Out, without the identity politics. She seems to be typecast as an intense character like the ones in La Pianiste and Elle. The Irish-Canadian-NY co-production in three countries may have something to do with the unevenness, which is the “reality of independent film,” especially for post-economic-crisis Ireland: Toronto’s Bay subway station featuring as New York in this film or as Boston in The Handmaid’s Tale. “The house in Dublin,” Jordan contends, “has elements of Hansel and Gretel leaving crumbs, the European monster and American innocent.”

During the Q and A session, Huppert said she loved her first horror film and “found the script very funny” as she improvised a scene with Stephen Rea where she is seen dancing to Chopin. Jordan prefers calling it a psychological thriller rather than a horror film: “How grotesque any situation [can be]. So grotesque that it is almost funny.”

Jordan’s favourite sequence is the double dream sequence, which has “a familiar alcoholic terrifying feeling” of the mundane: situations of loss, manipulation, friendships gone awry, stalking and trauma. Comic relief punctuates the tense moments. In an attempt to shake Frances from her naïveté, her best friend interjects, “Did I just snort crystal meth? Manhattan is going eat you alive.”

“There is always a guy in such stories… a deranged guy like a computer nerd,” Jordan told the audience about the logic motivating the villain in this film. One wonders if the playwright’s relation to his mother, her constant badgering, inspired him to pen this thriller.

TIFF has always been about selling and buying. People kept asking me which stars I had seen, and when I mentioned them – blank stares. At the Elgin Winter Garden Theatre, I noticed Atom Egoyan and his wife, actor Arsinée, in their seats. My friend forbade me to approach them but quipped I should ask Arsinée for her signature whilst ignoring the director. You often see young fawning masses waiting hours near hotels in Yorkville or the Variety party at Momofuku. One must wonder if they attend any of the screenings. After watching Isabelle Huppert piling into a black van, I noticed Neil Jordan signing mementos from Irish ex-pats. A man behind me asked me who he was. I obliged, “The director of The Crying Game.” “Never heard of him,” he announced within earshot of Jordan.

FROM THE UNCANNY TO THE CANINE

Matteo Garrone’s Dogman starring Marcello Fonte as the titular dog groomer won Best Actor at Cannes. He discovered his calling in a prison theatre troupe, and went on acting on television with shows such as Don Matteo and La Mafia solo uccide nell’estate. Garrone couldn’t attend due to his filming schedule in Italy, and sent Fonte instead to Toronto, who recognized that he wouldn’t have had this part if it weren’t for the death of an actor in the running. With Fonte’s particular face, you cannot think of any other actor playing the simpleton single father navigating loyalties, trying to do the right thing for survival in his personal sense of morality. The precision in the acting, caring for the canine, whether at his workplace or in the show-dog competition sequence, comes from actual dog-grooming classes.

Fonte stated that the film is “the story of the little man,” the victim of the local bully, drug fiend, man-beast, sometime friend and partner-in-crime, Simoncino. The familiar landscape of desolation of Gomorra is echoed here. This time it is the seaside in Campania built by the US Army only to abandon it – perplexing the audience with their ideas about Italy. Dogman is based on a true crime story of Pietro De Negri, Er Canaro, but not to the point of “re-telling” it, says Fonte. Garrone’s penchant for such poverty porn, as other critics superficially contend, is a stylistic choice he honed in The Embalmer, while Tale of Tales is based on Giambattista Basile’s fables where the set is hyper-stylistic.

The harshness of the landscape and narrative is tempered by Mina’s Il Cielo in una stanza – literally heaven in a room – a piece included only in the trailer of the film. Is it his love for his daughter, Alida, or his dogs, or the sense of abandonment under the immensity of the sky? The Gino Paoli song isn’t in the film’s soundtrack at all. Garrone preferred the film to have a minimalist, atmospheric soundtrack inspired by Lucio Fulci’s giallo, Don’t Torture a Duckling, specifically Florinda Bolkan’s murder sequence as well as the use of the Ornella Vanoni song in the scopophilia scene of a boy watching a reclining nude, Barbara Bouchet. There is nothing sensual in Dogman, just a compassionate lens.

After apologizing profusely for erroneously thinking he was a non-professional actor (since Garrone has worked with new faces, in-and-out of prison), I told him I had been looking forward to the film ever since I watched the trailer. Fonte gave me a wet kiss as a Dogman would.

VOICELESS ROHINGYAS

Manta Ray is the debut for Thai director and cinematographer, Phuttiphong Aroonpheng, who won the Orizzonti Award at this year’s Venice Film Festival. The film is elegiac and silent for the first 20 minutes, where his cinematography background abounds. His handheld camera in the mangrove follows a black-clad sniper wrapped with Christmas lights on a manhunt, and we witness a tied-up body in a ditch. Aroonpheng breaks the 180-degree camera rule of classic Hollywood cinema when our nameless fisherman protagonist returns to save the injured, whose wound continues to bleed after being bandaged with gauze. The victim vomits after eating his first meal since his famine-ridden experience. The shell-shocked visitor cannot communicate in Thai or any other language, and our protagonist names him Thongchai, after a singer.

The home has flickering “Christmas” lights, strobe lights reminiscent of Marie Menken’s experimental short, Lights (1966), where the men dance, a sensorial return to life. Lights appear in the lush green forest, punctuating the screen like fireflies. Later we realize they are gemstones hidden underground, which sparkle in the full moon. Our fisherman narrates that his wife left him for a sailor (who is incidentally less handsome), taking the gemstone bracelet he had made for her. “Dead bodies in the field. Nobody goes into the forest. Nobody knows where they come from. Scares people from entering at night.”

There is no narrative device guiding us to read the symbols in the film. We wouldn’t even know if the prey, Thongchai, is a Rohingya if it weren’t for the opening credits. Aroonpheng did not agree with the dedication in the opening credits because the character could be any refugee. He didn’t want to reveal too much, but the film is evidently about the crisis. On why he left Thongchai mute: “because the Rohingyas remain voiceless.”

The fisherman takes Thongchai under his wing, teaches him to fish, teaches him to breathe under water for diving, to attract manta rays with gemstones – for they come after a monsoon, and when the sea is calm they leave. When hunting for crystals in the ground, Thongchai unearths a dead baby, reawakening memories of the genocide.

One day the fisherman does not return home. Once again Thongchai is alone, searching for his rescuer until the captain of their sea trawler tells him that the waves took him away and his body was never found. Fisherman seems to work for the captain as the clean-up man in the slave trade of Rohingya run by Thai gangsters. Thongchai begins to wear Fisherman’s clothes, takes his motorcycle, his job on the sea trawler – the embodiment of foreigners stealing our jobs.

Fisherman’s wife returns, for her sailor dumped her after she became pregnant. She returns only to find Thongchai living in their home. She takes him to the hot springs and pines for her dead husband. Thongchai morphs slowly into Fisherman, catching crabs in the mangrove, with Fisherman’s wife metaphysically seducing him by taking him shopping at the night market, buying him a shirt of his own, enjoying the ferris wheel under the kaleidoscope of colours. Fisherman returns from the dead, peeps into his former house and life, finds his wife bleaching Thongchai’s hair like his own – the replacement is complete. Fisherman takes revenge on the captain boss and comes home to the wife whose excuse for shacking up is, “I thought you were dead.”

Fisherman says he can’t stay here. Thongchai knows he can’t either. He runs to the ocean, strips off the fisherman’s clothes and starts to hum in the water like he was taught, to breathe while diving. Souls represented by the lights emanating from the gemstones in the forest are alone in the cosmos where no justice can be had. The non-diegetic soundtrack emits electrifying sounds, like live wire in contact with water. The French composers were asked to create low-frequency sounds of a heart beating, which we can deduce is of a person in flight, running for their life. In the ocean, Thongchai drowns and a Manta Ray appears, black like a Rohingya.

Aroonpheng said he came up with the idea of the title from the location itself, when he saw this giant creature while diving near the Myanmar border. His friends asked him what the film has to do with Rohingyas? He started questioning the role of the artist prior to the Rohingya crisis. His 2000 short film was about copying another artist: the nature of art, being mechanized and reproduced. He cites David Lynch as an influence, as well as Apichatpong Weerasethakul. The opening scene in lush foliage with a black-clad sniper in Christmas lights is lifted from Weerasethakul’s Uncle Boomee Who Can Recall His Past Lives. He is also interested in national identity questions. The image of Alan Kurdi on the beach in 2015 made him delve into social issues concerning the refugee crisis.

He says the film is essentially probing identity issues. “Thai society has never met a Rohingya. The idea where a guy replaces another, the replacement of the citizen” is the central theme. He didn’t follow his 30-page script much, since he had just a few days of filming. He continues, “Society is afraid of [outsiders]. In 2009, 300,000 Rohingyas on boats were not allowed into Thailand by Thai authorities, and 300 of them disappeared.”

Without alluding to the slave trade in fishery that one member of the audience was pressing him on for a comment, the director walked a tightrope of self-censorship in responding to this accusation of complicity. He said there was “no problem with the government because it didn’t know I was filming, and release of the film will not be a problem.”

MANTO: THE SUBCONTINENTAL MADHOUSE

Nandita Das is a female actor and filmmaker from India fighting for the de-stigmatization of dark skin within Indian society. Her biopic on Urdu journalist, screenwriter and short story author Saadat Hasan Manto, in the turmoil of the Partition of the subcontinent, is conventional filmmaking – not to be confused with the 2015 Pakistani musical also entitled Manto. Manto, played by Nawazuddin Siddiqui (The Lunchbox), was born in Mumbai and ends up alcoholic in dry Lahore. Dislocation, like the refugee in Manta Ray, is the main theme. Das opens the film by dramatizing Manto’s controversial story, “The Smell,” about a young girl who is sent out by her father to entertain rich men who’ve paid lots of money for the scent of her pubescent armpit.

In 1946 such realism is too much, for he garners his first obscenity charge. In a Bollywood film production, Manto is angry when the lines are changed. The literary circle he belongs to – Progressive Writers’ Association – includes a female writer, Ismat Chughtai, who is acquitted in her first obscenity trial concerning “The Quilt” – a story about two women in a relationship. He falls out with the circle because they still want to write about British atrocities, ignoring present-day taboos and the struggles of women. Manto defies them: “Why not prostitutes? Prostitutes who kill their pimps?” His ambivalent stance about colonialism – “when British left dams, telephone” – sets him apart from the intellectuals. However, he is hopeful that the baby his wife is carrying shall be born into a free India.

The film posits that the reason he is attracted to women’s issues is because he is surrounded by strong women. His wife, Safia, wonders how he can imagine these short stories while the couple stare at a woman with facial hair at the park awaiting her partner. The humorous interplay is highlighted by music as the two weave a story about Hameda with a horse braid whose lover shaves both of their faces.

The perennial Hindu-Muslim conflict is central to this period. Hindu fundamentalists rioting in Mumbai’s Muslim neighbourhoods chanting, “We’ll kill you Muslims! Burn! Muslims go to Pakistan. Long live India!” doesn’t persuade Manto to move to Pakistan as his wife pleads, “Jinnah says we are safer there!” Manto is unmoved because his family, including son Asif, is buried “here.”

The Bollywood industry is also facing a sectarian backlash, where talkies are being produced and studios are accused of hiring too many Muslims, in open letters by anonymous writers. Other studios are employing fewer Muslims. Manto sends his wife, kids and sister to Lahore for their safety. Ashok Kumar, a Hindu Bollywood actor, refuses to wear Manto’s Muslim cap in a Muslim neighbourhood where he is welcomed as a star. Manto has both Hindu and Muslim caps to fit in with whichever part of the city. But Shyam, his best friend and another real-life Bolly actor, starts changing his demeanour when his uncle Manjeet is killed by “bloody Muslims” in Pakistani Punjab, conceding that it is possible that one day he could kill his friend too. Manto starts all his stories with 786, a promise of religious importance he made to his mother, using numerals for the invocation of Allah that is only used by Muslims in Indo-Pakistan area.

In Lahore, 1948, while Manto is working for Urdu newspapers, he witnesses a teen agitatedly exclaiming that Gandhi has been killed by three bullets shot by a Hindu. There is no indication that we are embarking into literary vignettes, for those of us not familiar with Manto’s short stories. His displacement and the stories he witnessed become his inspiration. In “Khol Do,” a father can’t find his daughter Sakina in the confusion of post-Partition train massacres. When he finds Sakina at the hospital morgue, she is half-alive, removing her drawstring from her shalwar as an automatic reflex. Dead bodies don’t move. This story depicts countless stories of women raped by vindictive mobs as witnessed by many during the Partition of India and Pakistan. Women’s bodies often become the battleground for war and strife.

Manto finally gets his first obscenity trial in his new homeland for “Cold Meat.” He has already faced censorship from an editor laughing at Manto’s penchant for using pencils over typewriters and Sheaffer pens, when Manto divulges that he uses pencils to erase his editor: ”If you never erase your words, would anyone else?”

When Pakistani officials get wind of his “Cold Meat” story, officials come with a warrant to rifle through his papers. “Cold Meat” re-enactment features a Sikh man confronted by his jealous wife, who aggressively pursues sex, mentions throwing his trump card as a euphemism (only to confuse impotence with infidelity), and plunges the kirpan into his neck. With his slit throat, he confesses killing seven people with the same dagger. Along with this, he confesses necrophilia with a dead girl. Manto is charged for sick, perverse and filthy language, and the corruption of youth. To add sting to the wound, his writer friends are called upon as witnesses, claiming “freedom to write is to write responsibly.” Faiz Ahmed Faiz from the Pakistani Times devastates him the most in the witness box by stating: “It is not obscene but not up to the standards in literature.”

Acting as his own defence solicitor, Manto cites a line in a poem and recites it to an Imam to judge the context. The Imam confidently declares that it disgusting, but reels incredulously once it is revealed that the writer is no other than the great mystic Sufi poet, Mir Dard.

Manto compares his trial to those of James Joyce for Ulysses and Gustave Flaubert for Madame Bovary. The judge decides that speech alone is sufficient to convict, and sentences him to three months’ imprisonment. Upon his release, Manto demands his old column back.

Manto’s most personal story is “Toba Tek Singh,” named after a town in Punjab. It is emblematic of the Partition and Indo-Pakistani relations, and is inspired by his detox in a mental asylum after learning about the death of his friend Shyam. During Partition, India and Pakistan exchanged lunatics along with criminals. Most of the men in this madhouse – an allegory for displacement – are affected by PTSD. The old Sikh man, Bishan Singh, was born in Toba Tek Singh under the British Raj, but is now in Pakistan. Marooned in No Man’s Land between the two borders, Singh falls in between the barbed wires, tells the officials to go to hell, and dies. “[In] a place with no name lay Toba Tek Singh.”

At a more personal level, Manto feeds his dislocation by going into a downward spiral of alcoholism; the affliction is exacerbated by being left unpaid by his editor, who was looking for lighter material for Rs.20.00. Manto cannot see past the murders: “enslaved, differed, which is my country? The 1857 uprising? The East India Company?” In one very short story, a man takes a knife to a pregnant woman’s belly but finds that he has made a mistake when the male victim’s circumcision indicates that he is a fellow Muslim. Manto falls out with fellow writers who call his work depressing and nihilistic. In turn, he critiques “Life for so-called Progressives looking for a positive silver lining.” His in-laws hate the fact that he doesn’t work, and his alcoholism causes further marital rift. He thanks alcohol-selling Parsis who make Lahore feel like Mumbai. He lives in the Lakshmi mansion where Hindus were butchered, a reminder that death hangs over him: “What has been forgotten? What is to forget? A simple man is to forget.”

The film has not resonated with non-Desi critics, due to the verbosity of the script that most biopics on writers tend to display. This is the reason #TimesUp is demanding more culturally sensitive reviewers.

3 FACES: CHANNELLING KIAROSTAMI

Barred from travelling outside Iran, Jafar Panahi came to be known for his women’s issues themes from The Circle and Offside. After the 20-year ban imposed on him, he had to film in taxis. In 3 Faces, Panahi isn’t confined within Tehran, and musters all his creative resources to circumvent the ban. Technology, an iPhone in this film, is the gateway to the current debate on viral videos with faked, staged or doctored images. A slo-mo thriller/road trip about technology and media, even if it is set in a town with power shortages.

Actress Behnaz Jafari, who plays herself, gets a troubling video message from Marzieh, who pleads to her most trusted friend to relay the video to the actress who has ignored her texts. The sense of urgency in her voice, her message that her family has betrayed her and wants her to rescind her place at the acting Conservatory to marry, ends with a “forgive me,” a noose inside a cave, and some blurred action as the iPhone is dropping. The guilt-ridden and tenacious actress abandons a film set and drags real-life Panahi – since he speaks Azeri like the girl – on a mission to find her whereabouts and find out if she committed suicide or if it was a prank.

A critique on the place of women in Iranian society is often in the foreground with Panahi. Questions surrounding Marzieh drives the narrative: whether she committed suicide or not. If she did, then did the family move the body and bury it to avoid village shame, seeing that suicide is such a taboo in these remote areas?

Throughout the road trip and misadventure, we peel this simple story from the hinterland and get a sense of how it relates to Panahi’s own predicament – being accepted for international awards (like the Cannes Best Screenplay award for 3 Faces), but not being able to travel outside Iran to accept them. The film mirrors this through Marzieh’s acceptance into the Conservatory but her denial by the powers that be – her parents.

There is still filming from and within a vehicle, with imagery of trees and stops at houses. Sometimes the camera channels Abbas Kiarostami’s rural landscapes. Upon arriving in the town, characters speak Azeri, and the older man chastises Panahi for forgetting his mother’s Turkic tongue. He tells Panahi about their honking system to warn drivers coming from the other side of the mountain, to avoid collision on the narrow road. An emergency gets two honks. The handheld camera captures unpaved roads. Jafari notes that if there is a wedding in the village, that means no mourning. On their way to the cemetery to see freshly unearthed plots, the villager opines that they don’t look like treasure hunters and in any case, in the old cemetery all the treasures are gone. They meet an elderly lady who has dug her own grave –“her final abode.” Lying deep inside, she brings a lamp to ward off snakes.

In town, the villagers finally recognize Behnaz Jafari and ask for autographs. The men are upset that they hadn’t come to highlight and film the town’s problems with cuts to electricity and gas. They figured they came for Marzieh, the “empty-headed brat.” Her oafish brother denies them entrance to the home. “First studies, then what? She dishonours us.” The mother locks up the raving brother and tells the duo from Tehran that they are looking everywhere for her and fear that they will “lose face in the village.”

The investigators go to the cave and find the branch in the video. They sense it is a staged hoax. Panahi asserts, “You expect that it will be here? The phone? A cover up! They staged it for us. It’s their honour.” In another meta-moment, Panahi’s line about a familial cover-up alludes to not believing what you see and doubting images like the ones found in official state news, in the wider argument of censorship in Iran. Behnaz tries to allay the producer’s anger for having left the film, by claiming that she would have been useless on the set.

The mayor – the man who gave roadside honking instructions – says they “set their own rules here. Common sense is necessary. If one falls ill, we need doctors… [there are] more satellite dishes than people or wannabe entertainers. She does what suits her best. She won’t listen.” The town needs young people – “our lives depend on them, we are miserable.”

The acting profession isn’t well thought of in the area: “we don’t want entertainers here,” they say, referring to the dancer, Shahrzaad, who worked in films in pre-revolutionary Iran and now lives alone as a secluded spinster in her house, where she paints because she is banned from entering the village. She represents the indomitable female spirit. She isn’t fond of directors: “Directors, they’re all the same,” but ultimately gives a parting gift to Panahi, a CD of her poems. The name alludes to a mythical weaver of tales for survival, Scheherazade, a Persian literary figure. Like with Marzieh, there is an element of life at risk, marriage against a woman’s will, an unreliable narrator, ending with a cliff-hanger. Panahi probably wove all the narrative devices from the epic tale, winning the Best Screenplay Award at Cannes.

One character in the village teahouse asks the actress about her TV show: “Since you are here now, show me how it ends?” She replies, “The usual: tears, mourning, the death of a character.” The viewer fears the worst for Marzieh, if this dialogue’s intertextuality renders a sense of foreboding for our story.

Panahi leaves Jafari at Shahrzaad’s home to find the town’s only road blocked by Golden Balls, a sickly bull whose owner needs a mobile phone to call a vet in time for the fair the next day. The meeting becomes philosophical: “Even humans are put out of their misery.” But the farmer is resolute in his beliefs: “Suffering is not up to you to intervene, but God’s will.” Golden Balls is a much sought-after bull for breeding. His testicles are miraculous: “one sniff of him, local cows swoon,” and the farmer offers his card for kebab delivery. Marzieh’s father also has queries about the cost of meat in Tehran.

There is a humorous and strange souvenir a father gives Panahi to plant in Tehran to influence the fate of his son, Ayoub, making Panahi the boy’s godfather and keeper of his destiny. The father had tried in vain to bury it near the Palace in the hopes that his son would get a janitorial job there, but the Guards arrested, jailed, and beat him.

In the final scene, 3 Faces is at its most poetic with a serpentine languid road in the depth of field. The ambiguous ending, when a white veil is thrown to the wind while cows come in for the fair from the other end. The clash between rural versus city values remains timeless and universal in the face of history, technology and extinction.