The South Asian Film Festival of Montréal (SAFFM), launched by the Kabir Cultural Centre in 2011, has grown year by year in scope and reach. This year it runs over two weekends: October 27-29 and November 3-5.

http://www.saffm.centrekabir.com/en/

Veena Gokhale spoke to Dipti Gupta, member of the programming committee. Gupta teaches at Dawson College in the Department of Cinema and Communications. She curated the SAFFM with Karan Singh, a Montréal-based writer and filmmaker.

V.G. The films chosen for this year look really interesting and innovative, taking on various issues. They include short films and feature-length movies. What, for you, are the highlights?

D.G. We have a diaspora panel with four Montréal-based, South Asian filmmakers (Eisha Marjara, Arshad Khan, Karan Singh and Ameesha Joshi) and one from San Francisco (Pallavi Somusetty). Our aim is to encourage and engage with the diaspora filmmakers, and start the conversation on the kinds of films they have been making, what more can be made, and the stories that are part of this community. I hope we learn more about their journey.

We are celebrating the work of Ali Kazimi, a distinguished filmmaker based in Toronto who has made some very important documentaries. We will chronicle his work and show one of his latest films – Random Acts of Legacy.

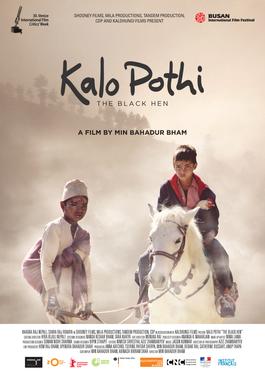

We have award-winning films, and films that are premiere presentations in Canada. The wide range of stories include refugee camp uncertainties and longings in Northern Pakistan in A Walnut Tree, observations on the Maoist movement in the mountains of Nepal in Kalo Pothi, deep insight into North American immigration in From the Land of Gandhi, and a film that celebrates colour but is shot in pristine black and white, A Billion Colour Story. Also on the program are films like A Ballad of Maladies, which captures the struggles of artists and their survival in highly militarized Kashmir, and Mukti Bhavan (Hotel Salvation), a comedy about family and relationships, the rigidity of religion and the demands of blind belief, while debating life and death.

Some of the Festival’s bolder films include Lipstick Under My Burkha, the story of four women who attempt secret acts of rebellion to break the monotony of their lives. The film attempts to shift the male gaze in cinema and was censored for several months, finally receiving clearance from the Censor Board in India. There are also films sponsored by Kashish Mumbai International Queer Film Festival’s Global Initiative, focusing on LGBTQ issues in and around South Asian communities: Transindia, Normalcy and Any Other Day, along with Escaping Agra.

V.G. I noticed quite a few LGBTQ films featured this year. Can you speak about them? Was it a conscious choice to include LGBTQ films?

D.G. I beg to disagree. Of the total 19 screenings, we have only 3 short films that speak to LGBTQ issues. Our aim is to bring in a variety of issues, and we like to explore themes that are underrepresented or have had no visibility in the past years. There are several artists/filmmakers in South Asia who are focusing on marginal communities and identities that had been taboo in the past, including LGBTQ, migrants’ stories and stories of people who have not been part of the mainstream. If you look at our program, you will see a lot of these voices represented.

V.G. One of the films you are opening with is Manto. You are screening an extract from this bio-pic about the Indo-Pakistani author Saadat Hasan Manto. He is a towering figure in South Asia, but audiences here may not know him. Could you tell us who he was and why he is important?

D.G. I read Sadat Hasan Manto, an Indo-Pakistani writer and playwright, during my tweens and was fascinated by the strength of his writing. His story “Toba Tek Singh” still resonates in my psyche. Here, the author addresses the fact that in 1947, when India and Pakistan became independent, the people in both these nations continued to remain slaves to prejudice, religious fanaticism, barbaric acts and inhumanity. Sadly, to this day, we are embroiled in the same tensions and we witness this everywhere.

When I heard that Nandita Das was making a film on Manto, I was intrigued and wrote to her and her company. They immediately replied and sent us the short clip that we are presenting. We hope to show the full-length feature film next year.

Manto is a statement and represents an ethos. Today, in a world where free speech has become a privilege and is no longer a basic right, Manto speaks to the core of this debate. Thus we hope to start our festival introducing this idea to our community members. SAFFM would like to be a forum where free speech is celebrated and encouraged.

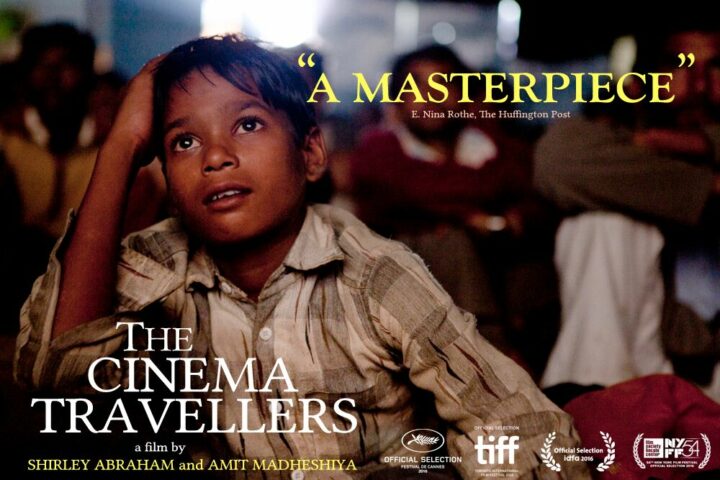

V.G. The second film on the opening night is the Cannes prize-winning Cinema Travellers, described as “a journey with the traveling cinemas of India.” You say on your website that distinguished filmmaker Rock Demers will be in attendance. What’s the link between the film and Demers?

D.G. We are very fortunate to have Rock Demers inaugurate our festival and do the talkback for Cinema Travellers. It is a story about exhibiting films in the remote villages in India where there is no access to theatre or cable television, and people watch films once a year!

Rock is an important producer of this province and of this country, and has been a huge fan and supporter of films from India. I also think that he knows more about Indian cinema than many people from India in Montréal.

In 1999, Rock produced Hathi (Elephant) directed by Philippe Gautier. When I saw that film, I was spellbound by the beautiful story of a mahout and his elephant. It was the premiere, and Rock talked about his love for India and Indian films. This registered with me, and I got to know him through some of my connections in the field.

Through the years, we have had several exchanges with Rock and learnt from him. Karan and I interviewed him in 2013 for our short film At Home in the World, where he talks about the kind of films he has watched from India, and their directors.

We felt that Rock would be the best person to talk about Cinema Travellers, given his background as a producer in Québec and the struggles he has gone through to circulate the work he has produced.

V.G. There are quite a few films by women film directors, and not all of them by middle-class women, as one would expect. It was heartening to note, for example, that there is a film by Manasi Deodhar, who lives in a small village in Maharashtra. Do you think it’s easier now for women to make films in South Asia?

D.G. Today, with changing technologies and greater awareness, I hope that the landscape is changing, and we have seen this. I agree that people in cities had/have more access, but I believe that there is strength in every sector, and everyone has a story. Today, a lot is being done on extremely low budgets. We received this film through a FilmFreeway submission.[1] This is a perfect platform for everyone to submit, and creates a kind of a level playing field. Both Karan and I choose offbeat themes and are keen to introduce filmmakers who are not that well known.

V.G. You are taking some of the films to Chicoutimi this year. How did that come about? I would imagine most of the films are subtitled only in English. Would this be a problem to taking the festival around in Québec?

D.G. Kabir Centre is always willing to explore presenting events in other cities in Québec. For this we need a local partner who can take care of the logistics and who can mobilize an audience. In Chicoutimi, we have Bibliothèques de Saguenay in that role, and this is the reason why we have been able to think of taking a mini-version of the Festival there.

French subtitles are very desirable for a location such as Chicoutimi, and we are planning to take some movies that already have French subtitles.

V.G. You decided to charge an entrance fee this year, which I think is a good idea. What was the reason for this change?

D.G. Running a festival such as SAFF Montréal involves a lot of expenses. In addition to resources that can be allotted from Kabir Centre’s own reserves, the board members are exploring the help that can be obtained from various funding agencies, donors in the community and local businesses. Ticket revenues are a small part of the solution needed for making the Festival financially viable.

V.G. There is a lot of emphasis on after-film screening discussions at SAFFM. Why is that?

D.G. I have always believed that any art form – cinema, theatre, painting, literature, mainstream or underground – only comes to its fruition after one shares it, discusses it. It is in the multiple interpretations and conversations that we reach the depth of its true expression. We hope that the talkbacks with the audience, with the filmmakers in attendance, with film scholars also present can push the conversations above and beyond what we see on screen. Festivals such as ours enliven local life. They are an attempt to start multiple dialogues, create understanding and build bridges across communities.

V.G. How would you describe the evolution of SAFFM?

D.G. Festivals always take time to take shape, and funding is always a challenge. It is never easy to find a permanent place to screen the films, procure the rights for them and invite filmmakers. This takes a lot of time and effort. Karan and I have been working on this for over 10 months.

Before 2011, Kabir Centre used to screen interesting movies as part of its film club. The decision to organize the screenings into a festival format was taken in 2011 in the context of the Year of India in Canada. In the initial years, the Indian High Commission helped us with copies of films that they had and also with auditorium rental. As the choice for the films expanded beyond old classics or current Bollywood films, we stopped approaching them.

Some years we have had a specific theme. For example, in 2011, we presented three films based on Rabindranath Tagore’s writings, as it was his 150th birth anniversary. In 2012, the theme was “Through a woman’s lens;” in 2013, “100 years of Indian Cinema;” and so on. In 2016, for the first time we invited submissions from independent filmmakers through web-based FilmFreeway, so our presentation was a combination of submitted and invited films. In 2017, we are continuing the same format, and have added awards for the best short and best feature films.

With time our vision has strengthened, and we have a better idea of what we wish to bring to the Montréal audience. Our attempt is to get a wide range of films, and each year we are slowly trying to reach more filmmakers.

The Festival is meant to be a window into the dynamic world of cinema from South Asia. South Asian cinema is not homogenous, and is in many languages. I often see that the language aspect is lost in translation, and the subtitles do not do justice. This is always a challenge during programming. We hope that as the festival strengthens, we will be able to attract more representatives who speak multiple South Asian languages.

SAFFM is a platform for artists to not only submit their work, but also be present in person. We have guest filmmakers who are travelling from South Asia and other parts of the world to join us this year for audience talkbacks and panel discussions. Our attempt is to encourage intercultural dialogue through our choice of films.