In the past couple of years, we have all discussed and dissected, with intensity, the man-made climatological changes that have hit our earth. It has become frustratingly clear that it is not enough to debate the science, the predictions and the impact on our future lives on earth, as our only channel of activism. Climate change is not simply a result of bad habits and poor science, but a systemic overpowering of peoples’ choices through the erosion of the strength of the commons and the right to assemble freely and converge together for a more cooperative and sharing society.

The commons generally refers to:

“… the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society, including natural materials such as air, water, and a habitable earth. These resources are held in common, not owned privately. Commons can also be understood as natural resources that groups of people (communities, user groups) manage for individual and collective benefit. […] Commons can be also defined as a social practice of governing a resource not by state or market but by a community of users that self-governs the resource through institutions that it creates.” (Wikipedia)

Vast segments of the country are part of the commons, places where public jurisdiction or public access is not something that can be constrained. Parks, forests, river areas, wetlands, falaises, the migratory pathways (in the skies and on the ground) of birds and animals immediately spring to mind. But the commons also includes parts of a city – the urban landscape, the parks and plazas outside subway stations. These are areas where the poor can congregate to afford themselves some pleasure… the public version of the backyards of folks in gated communities.

The commons is where people meet and have a right to congregate. It has to do with human rights and individual freedoms, where access to essentials like water, food and shelter are controlled by local populations and not by private interests.

Political decision-making in the shadows

There is a nebulous political structure that decides how many school playgrounds a borough will have. In local government, who decides where social issues can be resolved? Who decides to cut trees to build a soccer field – and how many trees to cut? How is the process of implementing public welfare decisions constructed (such as decisions on social housing, growing trees, forming cooperatives, etc.), and by whom? The whole cooperative decision-making process and cooperative living style – community living style – is not really in the cards, even though heroic movements have fought for it for decades, right here in Montréal.

All this is being discussed in various forums, but there is not enough impetus for preserving the public wetlands, forest areas, parks, mountains – everything that surrounds the city and everything in the city that could be defined as the commons.

Many of us are deeply concerned and worried about what is going to happen, not just for the next five years but for the next twenty. Where do we stand with all this? It seems to us that the climate movement has waged a fairly decisive battle in making sure that this man-made crisis is clearly identified for what it is. However, the same climate movement has very limited controls over any decisions that governments may have arrived at as a result of signing on to certain targets.

Very simply put: large, polluting, fossil-fuel-using nations routinely renege on targets or opt out of programs. Canada is one of them. We have decided to deliberately miss our 2030 targets by 15%. There are limited political watchdog surveillance systems that monitor the provincial and federal governments’ actual performance in curbing our ever-increasing capacity to exploit our natural resources.

There is something else looming large that is not being discussed enough: a shadowy image in our minds of an ever-growing political structure that is preparing subtly to oppose environmental measures through a variety of sustainability-friendly measures that are combined with coercive policies in non-sustainable areas. The forces of privatization and the fossil fuel industry are surreptitiously rebranding their claims. The climatological battle cannot be won unless we curb privatization and fight for the public commons.

The environmental movement in Canada has parked itself outside the obvious areas where jurisdictional decisions are taken. Having a Green Party or an NDP with a competitive green policy is patently inadequate unless these parties are part of a political movement that operates in the commons. And the movement for the commons has to integrally respect Indigenous land rights and cultural heritage.

In this issue

Our issue features a photo essay on the Wixárika people’s opposition to a Vancouver mining company’s operations in Mexico. Photographs by José Luis Aranda and commentary by Serai editor Claudia Itzkowich highlight these Indigenous activists and the sacred land of Wirikuta that they are committed to protect.

Freelance journalist Patrick Barnard makes the climate crisis personal in “First Person Climate Change.” Reflecting on science and the weather and key figures shaping his consciousness over his life time, from CBC’s Bob Carty to Moby-Dick, Patrick implores us to halt the “mad narcissism… the driving force of the world as it is organized today.”

Blossom Thom, poetry co-editor of Jonah Magazine, speaks in her poems of yearning, love, and oceans shouting to the shore, sleep collected in remnants, gold dust coating our throats. In “The Garden of Dutiful Women […] whirling, we step on the edges of blades.”

Rae Marie Taylor, author of The Land: Our Gift and Wild Hope,” ponders the distance separating humans from the natural world since the Industrial Revolution, and the need to reclaim our wildness and preserve the commons. In “The Root of It,” she writes: “We need each other and the land that speaks to us of life other than our own. We need the tides and the shores of our planet […] the forest and the hills, the plains and the rain, the elk […] We are necessary to their survival. They are as necessary to ours.”

Better known for directing plays and films, Guy Sprung reflects and muses in his poem, “Dusk on Loukes Lake:” “I float | downside-up | in a darkening world…”

In her poem entitled “Dhrupad of Destruction,” Savitri Sawhney evokes the eternal dancer of creation, conservation and destruction in Hindu mythology, Nataraja, dancing “to the sound of crushing ice, melting glaciers and rising seas.”

Vrajesh Hanspal’s dark poetic prose piece, “Forest Floor,” plumbs our more sinister imaginings of the forest and its carpet of organic detritus teeming with the crawling, ticking and cooing creatures that respected no boundaries…

Two incisive poems by Paris Elizabeth Sea tear into our theme without mincing words, in Moment, arriving.

Maya Khankhoje reviews a highly original novel by Brenda J. Wilson entitled TAKEWING a.m., which centres on the yearly migration of the monarch butterfly from Canada to Mexico and back.

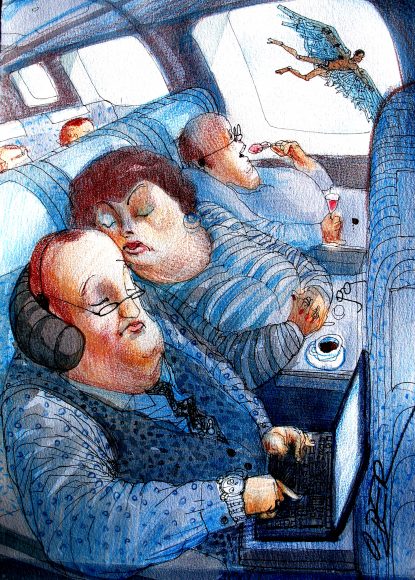

And this editorial features a drawing by Canadian cartoonist Oleg Dergachov, commenting on human obliviousness as we fly too close to the sun.

We hope our issue boosts your spirits and stirs your creative juices as we spin new filaments of community in this uneasy time of Corona.