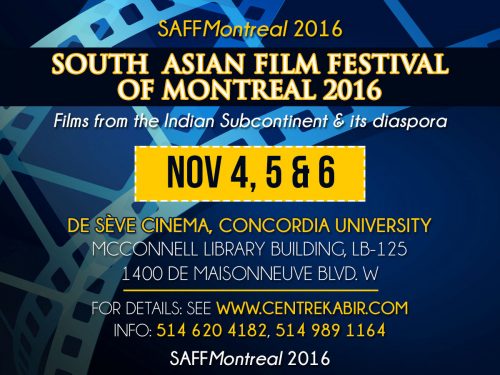

Kabir Cultural Centre (Kabir Centre for Arts & Culture), an important institution in Montréal, launched a South Asian Film Festival in 2011. With the approach of the 6th session of the Festival, Veena Gokhale spoke with Festival Director Dushyant Yajnik, a Board member at the Centre, about its vision and the Festival programming.

For Festival details, please visit:

http://www.saffm.centrekabir.com/

https://www.facebook.com/saffmtl/

VG: Your website says that the vision of the Kabir Centre is to promote harmony and mutual respect among Montrealers of South Asian origin, and in this process establish a bridge with the larger Canadian society, and that you do this through the medium of arts and culture. Could you expand on this vision and give us some background on how the Centre came about?

DY: In 2002, two progressive Montrealers of Indian origin – the late Daya Varma and the late Salim Omar – founded the Kabir Centre. In different ways, both had been active for many years in socio-political and artistic/cultural spheres with regard to South Asians in Québec and Canada. The Centre was incorporated with Omar Salim as President. T. K. Raghunathan is the current president, and is supported by an Executive Board of 14 members.

Kabir was a 15th-century Indian mystic, philosopher and poet. In his pithy, earthy and simple verses and religious songs, he criticized orthodox rituals and suggested an inner personal path of righteousness. Legend has it that he was a Hindu who was adopted by a poor Muslim weaver’s family. Many South Asians are inspired by his teachings, and take him as a model for the ideals of pluralism and harmony.

In naming itself Kabir, Montréal’s Kabir Centre aims to promote harmony and pluralism among the South Asian diaspora and build bridges with the larger Québécois and Canadian society through culture and art related activities.

Since its inception, the Centre has focused on presenting high-quality music and dance programs with well-known performers from South Asia. We have also made deliberate efforts to present local practitioners of South Asian arts, such as Aditya Verma, Jonathan Voyer, Julie Beaulieu, Shawn Mativetsky, the late Catherine Potter and her Duniya Project, Alexandre Brunelle Garon, Subir Dev, Sudeshna Maulik, Deepa Nallappan, Alexandre Lavoie and Krucis Khan. There have been many “fusion” music concerts with artists from other traditions in the world.

Kabir Centre also runs a thriving book and poetry club, screens films, and hosts the South Asian Film Festival (SAFF) in Montréal.

VG: I have personally experienced some of your fine programming. While music and dance from South Asia are not as easily accessible in Montréal, cinema is more present: there are movie theatres that show Bollywood films, and some independent and alternative films from the region are screened at Montréal film festivals and repertory cinema. Why did you feel the need for a South Asian Film Festival?

DY: We started with film screenings as part of our general programming, and the film festival emerged later on. As you said, Bollywood films already receive some exposure in Montréal’s commercial theatres, so we give them less priority. With the explosion in the number of interesting films from the subcontinent and its diaspora, there is always room to showcase independent and “offbeat” films that receive little or no exposure in Montréal. In fact, the problem for our selection committee is that we have had to decline some very interesting films because of the sheer number of such films and the limited number of screening slots that we have.

The Festival creates synergy and momentum among viewers. South Asians, along with film lovers from other cultural origins, and from the “mainstream” Québécois and Canadian society, have an opportunity to gather, mingle and participate in our stimulating post-screening discussions.

We received initial guidance and ongoing inspiration for SAFF from two individuals: Vijaya Mulay, filmmaker and Indian film historian, now in her 90s, and Thomas Waugh, professor in film studies at the Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema, Concordia University. We have also received other collaboration and help from the Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema.

VG: What is the vision for SAFF? How do you select your films? And yes, there is an embarrassment of riches to choose from, as you mentioned.

DY: Our vision is to show films that reflect life experience – the joys and struggles of South Asians. In our choice, there are films that are appealing and delightful but also engaging and arresting. Hopefully they show the human condition in all its complexity. We try to balance films from different countries of the subcontinent and diaspora communities across the world as well as among the different regions and languages of the Indian subcontinent. We show feature films as well as documentaries. There is usually a short film before the main feature.

VG: How is this vision reflected in the films chosen for 2016? What are some of the films you’re particularly excited about?

DY: If you go to our website and read the film descriptions, you will see the variety of stories and subjects covered. For example, we open the festival with Angry Indian Goddesses by Pan Nalin. Described as India’s first female “buddy movie,” it shows what transpires over a few days when a few young women meet for a reunion. They share their doubts and their desires, their conflicts at work and in their relationships, and the limitations and frustrations stemming from being female in India. Will the archetype of the Hindu goddess, Durga, be unleashed in them when an unexpected crisis happens?

Cricket and Park Extension: a love affair is by the award winning, Montréal director, Garry Beitel. To quote from Bill Brownstein, film critic at the Montreal Gazette, “The film offers an illuminating peek into both the sport and the community which supports it the most in the city. According to stats, about 50 per cent of Park Ex is populated by those with South Asian roots. More than 80 languages and dialects are spoken in this ‘multi-sensorial’ neighbourhood. While residents have become increasingly more integrated in the province and their offspring most proficient in French, they have kept a tradition brought from their homelands: their love of cricket.”

Kakka Muttai (The Crow’s Egg) is a Tamil film about the trials and tribulations of two young boys from the slums of Chennai who aspire to collect enough money to be able to afford a small pizza from the new fancy pizzeria just outside their slum.

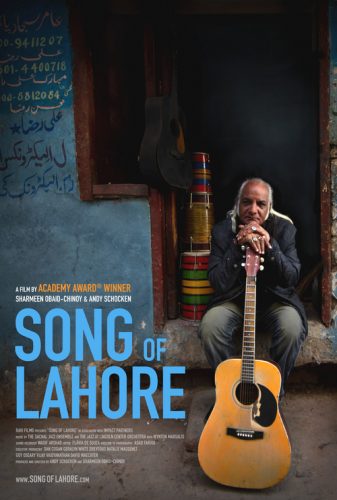

Song of Lahore is a new feature length documentary by Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy from Pakistan. She won the Oscar for the “best documentary short subject” in 2015 for her film, A Girl in the River, about a young woman who survived an honour-killing attempt. Song of Lahore is about a group of classical musicians who were disfavoured and went through hard times during Zia-ul-Haq’s regime. They come together and created an ensemble that plays jazz music on classical Indian instruments like the sitar and the tabla. The film follows them to New York where they are invited to perform with jazz trumpet player Wynton Marsalis and the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra. It has the spirit, poignancy and pleasure of American guitarist Ry Cooder’s film, Buena Vista Social Club, in which he gets some old and forgotten Cuban singers and musicians together, records them in Cuba, and brings them to NYC for a concert.

And I could go on like this about each of the other 14 films we have programmed.

VG: While the Festival is generally well appreciated, one critique I have come across is that you tend to shy away from films that reflect more radical, political views – those that sharply critique the Indian state. And, following on that, you tend not to feature subjects like Hindutva and the cultural impact of the extreme right in India, or Dalits (formerly untouchables) and Adivasi (indigenous) struggles for equality, etc.

DY: Kabir Centre neither shies away from nor goes after movies that critique the Indian state (or Pakistani or Bangladeshi, etc.) or deal with specific subjects such as untouchability.

We have screened films dealing with some of the themes mentioned above. For example, Amu, partly-inspired by the anti-Sikh riots in Delhi after Indira Gandhi’s assassination; Fandry, which is about untouchables; Something Like a War, about State-sponsored forced sterilization, and so on.

Kabir Centre is not an organization with any particular political agenda. We do not deliberately go after issue-oriented social or political films just for the sake of a particular issue, no matter how worthy or correct that might be from an individual’s point of view. We select (a film) as long as it is a well-told story that rings true of the human condition in all its complexity. The above subjects have, over time, ended up being reflected in our past film festivals. And this trend will continue.

VG: Given the dominance of India on the cultural scene in South Asia, do you find it difficult to find films from other countries in the region? Are there some examples of such films in the forthcoming Festival?

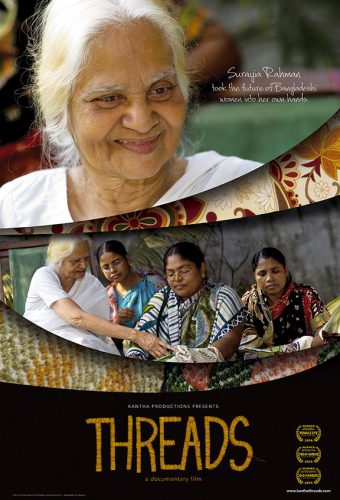

DY: Given all the information on the internet, following the lead of other more established South Asian film festivals in the world, and having joined a platform that connects film festivals and film submitters, our own programmers’ networks, etc., this task is easier now. In this year’s Festival, These Birds Walk and Song of Lahore are set in Pakistan. Threads is a documentary about Suraiya Rehman, a Bangladeshi woman artist who took inspiration from the traditional “Kantha” embroidery quilt work, and started a collective of destitute young mothers who create masterful works under her guidance. Two years ago we had a film from Sri Lanka, and last year we had a film set in Afghanistan.

VG: Who is your audience? Are you satisfied with the numbers of people who attend? What are your criteria for success? Do you feel there’s enough youth participation?

DY: Our audience is the South Asian diaspora from the countries and regions of the Indian subcontinent, along with many local non-South Asians who are curious, and film and culture lovers. We would like a bigger attendance, but that will happen as we improve our organization, publicity skills and outreach. This applies to youth participation as well. We are doing better publicity at McGill this year and in some of the CEGEPs. All our Saturday and Sunday afternoon film selections this year are appropriate for children.

Montréal’s multicultural residents attending the films in big numbers and being enriched by the stimulating discussions after each screening – that would spell success for us.

VG: How are the Centre and the Festival funded? Do you feel this funding is secure? Do you see the Centre expanding further through more government funding or by other means?

DY: By and large, the Centre is funded by the revenues from other ticketed events such as music and dance concerts, as well as sponsors from the community who are interested in its growth. This funding is not secure, and sooner or later the Festival will need to seek and obtain funding from government agencies and other funding institutions. This is part of our strategic plan.

VG: Can you speak a little about the volunteer aspect?

DY: The Film Festival is run on a voluntary basis with many hours put in by the festival committee members over several months. Other volunteers, including the Board members of Kabir Centre, also pitch in. The Film Festival committee for 2016 consisted of: myself; Dipti Gupta, faculty, Department of Cinema and Communications, Dawson College; Shireen Pasha, filmmaker, retired from the National College of Arts Lahore, Pakistan, in 2014 as head of the Film and Television Department; and Jill Didur, associate professor, English Department, Concordia University.

There is healthy discussion and debate in the programming committee before we arrive at our final selection. T.K. Raghunathan, the President of Kabir Centre, is also very involved.

VG: How many members do you have?

DY: We currently have around 200 members who pay a nominal annual fee. The members get approximately 20% rebate on their tickets for every event.