When the Editorial Board framed the theme statement for this issue of Serai on Nationhood, we asked in the opening paragraph, “What does nationhood mean today for the First Nations and other Indigenous peoples, who strive to navigate forward in a world hell-bent on leaving them behind?”

Did we have an inkling at that point of how the concept of nationhood, territory, borders and land and the state would be imagined and interpreted? We invited writers, academics, essayists and storytellers to huddle and contribute. From our diverse array of contributors, what has emerged is phenomenal and mind-bending.

First, the First Nations

To a certain extent, we did know that we would get phenomenally perceptive contributions. But when I personally went through the four-part presentation by Yves Sioui Durand in an interview with our editor Jody Freeman, a number of ideas unfolded in my mind. As an individual Editorial Board member, I realized that I had not understood many of the intricacies of settler colonialism and occupation, the initial forays into the fur trade by the European colonialists, the imposition of Christianity and the complexity of relationships of the various First Nations.

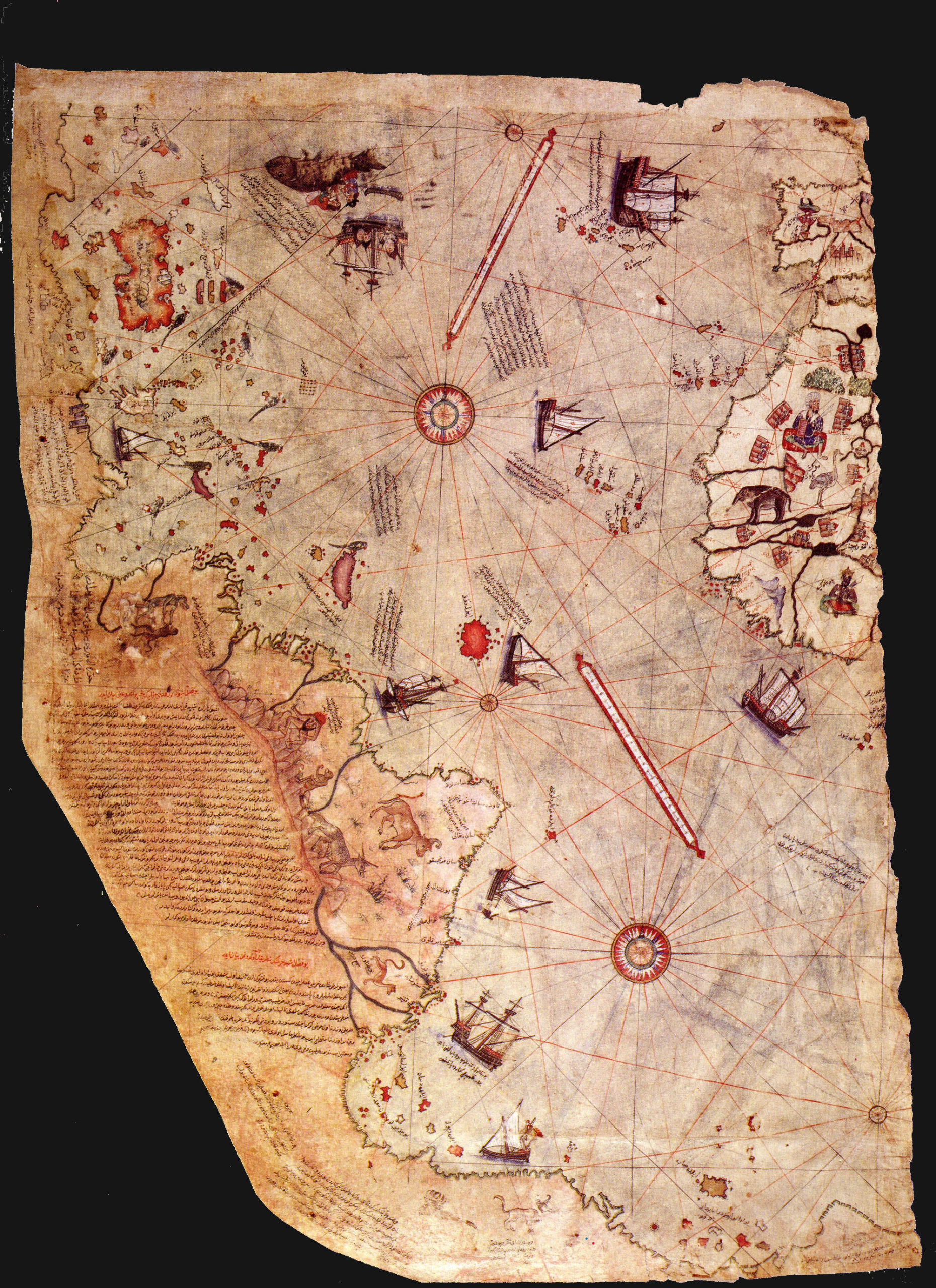

And how utterly foolish the quest for spices and gold by the colonizers, in heading further west towards Asia! It has been said (undocumented) that Vasco De Gama met Christopher Columbus and Jacques Cartier en route in the Atlantic, and told them to head the other way—then proceeded on to India himself!

Now, many of us may know about Yves Sioui Durand. He is an extraordinary artist and a documentarian of the history of the various First Nations. He is a pioneering member of the Huron-Wendat Nation. His deep grasp of the concepts and history of nationhood, colonization and the intricacies of the relationships between Algonquins, Abenakis, Huron-Wendat, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (or the League of Six Nations) and other nations feels like a fresh wind blowing over us. He is deeply reflective about Indigenous peoples’ history, not only in Québec and Canada but also globally, with special emphasis on the three Americas.

We are not only talking about the royally contracted adventurers of La Nouvelle France, Jacques Cartier and others, who travelled all the way down the Mississippi to New Orleans and Louisiana to lay their stakes down on the ground. They posed as rather benign imperial warlords (they were only making 400 percent profit on the pelt trade!) compared to the British colonialists, who came armed with decrees to systematically erase the history of the First Nations and Inuit, loot, enslave and spread their notions of civilization. And the fact is that the British triumphed in Canada and that is primarily the reason why we are confined to this torporific two solitudes (French and English) and a complete state of prevarication on Indigenous peoples, despite all the pretensions about it.

This leads us to a short and poignant essay by Tahieron:iohte Dan David about borders imposed on Akwesasne territory. He says, “Rather than get angry, I chose to find out more about things like this. Things that most Canadians could not conceive of as possible unless it happened to them. Although, to be fair, anyone who has arrived in Canada from another colonized country might understand how borders can simply be drawn without a bit of concern or thought to the original people who called a place home.”

In Haiti, a proverb says Pale franse pa di lespri pou sa

“Speaking French doesn’t mean you’re smart,” nor is it a fast track to intelligence. This Haitian proverb rejects outright the colonial language of enslavement and exploitation, and France’s colonial and post-colonial role has been succeeded, in English, by the US, Canada and anybody else who can get on the bus. This is why we asked our contributors, “What does nationhood mean for Haiti and other former colonies, which are still paying the price of past and present imperialism?”

Haitian-born artist Clovis-Alexandre Desvarieux was interviewed by our editor, Dave-Lentz Lormeus (aka DL Jones). An engineering graduate from Concordia University, Clovis has brigged over (a metaphorical old English representation of the current bridged over) to his interpretations of modernism, abstract expressionism and psychological cubism, combining them with multi-layered references to the liberation of the Haitian people and nation. In this issue we have highlighted his works on the magazine’s landing page as well as with the interview.

A significant book review on South Asian First Nations

We move on next to the Adivasis of India, literally “the first inhabitants” of India. At our request, in an incisive review of Alpa Shah’s book (Le Livre de la jungle insurgée, Éditions de la rue Dorion, Tiohtià:ke / Montréal; in English, Nightmarch, Harper Collins), Sam Boskey, former leader of the opposition on the Montréal City Council, has presented another exemplary notion of nationhood. Not only have the Adivasis declared their sense of nationhood in terms of their relationship with the land, the forests, the mountains and the rivers, they have continued to battle the Indian state for over fifty years. Their active struggle is a thorn in the side of the large corporations heavily invested in the environmentally devastating extraction economy.

This brings us to Veena Gokhale’s extensive and well-organized interview with Himmat Singh Shinhat after his solo performance of Panj at the MAI centre (Montréal Arts Interculturels) in May. This self-exploratory multimedia production covers the Partition of India into two nations, India and Pakistan. And believe it or not, a British cartographer in London, who had never stepped foot on that land, took a pencil and drew a line over the map of India and defined the two nations’ boundaries! Himmat has been associated with Serai from its very inception. A swell and swing guitarist/musician (killin’ it when it comes to Hendrix tracks), Himmat documents the migration precipitated by the Partition via his parents’ experiences and journey from the erstwhile India and Pakistan, first to India, then to the UK and on to Montréal—through songs, live performance, spoken word, and compelling slides in the background.

Sandeep Banerjee, professor of English literature at McGill, writes in an expansive frame of mind, covering and building brick-by-brick the notion of the nation known as India: “In contemporary India, in this second decade of the twenty-first century, a complex set of socio-cultural processes are seeking to imagine India (as) an exclusively Hindu country as they push the Indian nation gradually, but firmly, down the path of a blut und boden kind of nationalism. The need of the hour is to contest these ideas to re-imagine India once again as a nation of plurality and inclusivity.”

We then proceed on to Joseph Kary who has contributed previously to Serai, and who examines deftly and precisely the ecosystem of poorly concealed antisemitism and extreme right-wing nationalism in the organized mob that attempted a coup d’état on January 6th at the US Capitol. We have problems! If the nation just 166 miles away from us is on such a gruesome track, we have reason to be greatly concerned—and no doubt the convergence of occupiers on Ottawa was well thought-out and intended to divide the nation in an ugly manner… and it has.

Cyril Dabydeen, poet laureate emeritus of Ottawa and a frequent contributor to Serai, has provided us with a short story that is at once cryptic, humorous and telling.

In this issue, our contributing editor Maya Khankhoje reviews Montréal poet and writer Carolyne Van der Meer’s new collection of tender words entitled Sensorial. Here is Maya’s takeaway: “A rebellion against dehumanization is afoot and one of its sharpest weapons is poetry.”

I would have said to enjoy this issue, as it is a compelling intermesh of reflections on nationhood, nation states and the people who live on those territories. Nationhood, however, is not just about borders, bills, physical contours, customs clearance or toll gates. It is a state of ancestral learning and continuity—about lessons learnt in relationship to the land, the mountains, the forests, the skies and the people who have lived under it. It is about the historical and intellectual continuity of those who were there from before—the Adivasis (original inhabitants of the land, in Indian languages) and the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island and beyond. Nationhood is about them, their struggles, their opposition to colonization, their efforts to keep their languages alive, and their ongoing battles to protect the land.

But things are not looking good in this world (after the new election results in Italy, where a Mussolini addict has captured state power). It is necessary to review this global condition and not simply drown ourselves in distractions posing as culture and the arts. We hope you enjoy the issue nonetheless, and use the comments section to share your critical thoughts with us.

Special thanks to those who helped edit and revise the French texts: Muriel Beaudet, Catherine Browne and Sylvie Martel; to Alix Van Der Donckt-Ferrand for editing the videos of our interviews with Yves Sioui Durand and Clovis-Alexandre Desvarieux; and to Jessica Stillwell for helping edit the English texts.