Introduction

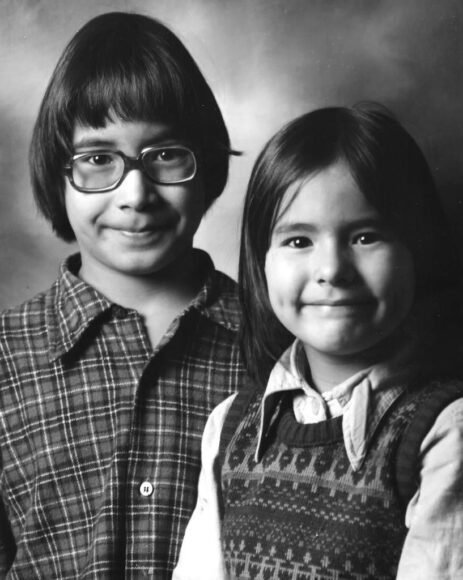

Michèle Audette was born in Wabush, Labrador in the early ‘70s, after her mother went into labour on a train taking her home to Schefferville, Québec. Her mother was urgently airlifted from the train to the nearest hospital. Within hours of Michèle’s birth, her Innu mother and Québécois father were once again boarding a train with their baby girl in their arms—in a segregated train car reserved for “les sauvages.” It is no exaggeration to say that Michèle has been engaged in the movement for Indigenous rights, women’s rights and social justice since her earliest moments on earth.

Montréal Serai editor Jody Freeman interviewed Michèle in mid-November 2020, a time of deep mourning in Indigenous communities and beyond, following the death of Joyce Echaquan, a 37-year-old Atikamekw mother of seven, in a hospital in Joliette, Québec. After suffering grievous mistreatment and racist insults at the hands of hospital staff, Joyce livestreamed a painful cry for help, exposing her cruel treatment in the final hours of her life. Her video sent shockwaves through Québec society, where the government continues to deny the existence of systemic racism.

Our interview began with a question about Michèle’s personal and professional choices and the path her life has taken, linking her to the stories and truths of so many others.

Michèle Audette: The way I see it, I’ve made choices in a context that was imposed on me. Since my birth, I was taught a beautiful legend shared by many (Indigenous) nations: every child is a little star in the sky before they choose their parents. In the actual world I chose, I didn’t know that from the time I was born, I would be in a space and time where segregation was officially fostered between “whites and savages,” as they put it back then. I decided to leave my mother’s womb while she was on a train in the middle of nowhere, heading north toward Schefferville.

An emergency helicopter picked up my mother and took me to the closest hospital, which happened to be in Labrador. A few hours after I was born, my first experience on earth was with my parents at a train station, standing between a train car for “savages” on the left and one for “whites” on the right. My mother had experienced that for years… for generations. But for me, that was my very first experience. That realization hit me really hard a few years ago.

That’s why I say that I made choices within an environment that was imposed on me: one of segregation that was transformed into other forms of systemic discrimination and policies that continue to marginalize us. I grew up in an environment where my parents, who were from two different cultures, tried to offer us the best of both. My mother’s culture was decimated by colonial violence, the effects of residential schools, the dispossession of our territorial lands, and everything that Indigenous women faced back then (and unfortunately still face today). My Québécois father wanted to discover wide-open spaces. But I was too young to understand that I didn’t have the right to live on my traditional territory and go to school and learn Innu, and awaken my five senses in a normal way—not by having to push people out of the way just so I could nurture my Innu identity.

I had fun in my childhood and my parents gave me love. But the context in which I grew up wasn’t healthy at all, and I went through trauma. I later discovered that the school I had to go to wasn’t a real school, it was a place where I had to follow the rules. I hate rules. At a very early age, I detested rules and I still am revolted by rules. I couldn’t speak my language. I couldn’t live in my community. The priest ruled. I wasn’t able to savour life in an environment where my language, my culture and my identity were protected.

It was hard. At school I was told that I didn’t have the right to make love before marriage, otherwise I’d get pregnant. I was told how to brush my teeth and which room to go to for vaccinations, but the school didn’t teach us about life. I didn’t get the same quality of education as my cousin who was Québécoise. When I went to another school later, in Montréal, we were treated as if we were slow learners and couldn’t understand anything.

That was imposed on me. And later I made some choices that hurt me, like not finishing school. At the age of 49, I know I’m going to finish school one day. For me, teaching is a powerful weapon to ensure popular education and reappropriate my history as an activist or artist—to provide the education that was taken away from us. Activism and defending causes came naturally to me because of that.

I have five children, who are young adults and young adolescents. They want to do the same kind of things that I do in my life, and ask me what I studied. I try to find out what it is that they think I do. They feel my influence, impact and power—but not power in a negative sense. There is not one single teaching that led me on a path of self-learning—there are woundings, traumatic events and other experiences and adventures that resulted in my being self-taught. They have the opportunity to go to school, and I’ll do everything I can to ensure that they do, so they don’t have to follow the same path as I did. They can share my experiences but learn in school, too.

Education wasn’t talked about in my family when I was a child. My mother was a nurse and my father, an intellectual who knew about American and European politics. I don’t know what degree he earned. He learned from life. My mother learned from life, from love, and from our traditional lands.

Jody Freeman: When did you start to be involved in women’s groups?

Michèle Audette: At birth! When my mother married my father, who was not Indigenous, she lost her right to live in the Innu community [under Canada’s so-called Indian Act]. And when they were divorced, she was still denied the right to return to her community. [She started fighting to change the Indian Act.]

I was born in 1971. My mother and I went with the Atikamekw, the Abenaki, the Mohawk, the Huron-Wendat and other nations, and we all created the association of Québec Native Women in 1974. From ‘71 to ’74, I was cradled and rocked by many women leaders. There is a ceremony in various regions to welcome newborn babies, including in Québec. A circle is formed, and each person takes the baby in turn and blows gently on the child, sending the child a thought. I think I had a lot of women leaders from those nations who infused me with their message when I was a baby. I can feel it. Most of those women are dead now, but they would remind me about that ceremony when I saw them. “You were so little, you slept on the floor while we held our meetings, and we rocked you.”

That’s when it started. But I was officially elected president of Femmes Autochtones du Québec at the age of 28, after serving as a young representative for two or three years.

Jody Freeman: Were you working with Indigenous women’s shelters at that time?

Michèle Audette: It was in that period that I met Françoise David and Manon Massé—encyclopedias of women’s rights—who were seeking Indigenous women’s support for the World March of Women. With the WMW, I realized that non-Indigenous women’s shelters and crisis centres were receiving far more funding ($300,000 in 1999-2000 for 9 beds) than we were ($116,000 for 16 beds). My priority battlefront shifted from changing the Indian Act to pushing the Canadian and Québec governments to play a role in Indigenous women’s shelters. Because of the demands—and battles—of the World March of Women, a national centre for women’s shelters was created in Canada, and a network for Indigenous women was created in Québec.

Jody Freeman: Was the 500-km march from Québec City to Ottawa also held during this period?

Michèle Audette: No, that was much later. When I was 33, I ran into a wall, emotionally and physically. I was depressed and burned out and felt ashamed about it. I passed out in front of a deputy minister and government officials, as I was defending an issue. The shame of it kept me home for weeks afterward. In politics, there were declarations and denunciations, but very little change. It seemed like what I did had no impact, and I was tired. And after I had my second family, including twins, I felt that I had to fight for my older son, whose right to have his [Indigenous] status recognized by Ottawa and his Innu community was still being denied. My younger kids were recognized, and my older child was not, because of a stupid law [the Indian Act].

I decided to go to Ottawa to denounce this injustice. Organizing a [500-km] march was a concrete collective action—a social and political action that mobilized people. And today, 45,000 people are able to claim their Indigenous status thanks to the march.

It changed my outlook. I realized that there were things I wouldn’t see in my lifetime, but I still had to fight for them without any immediate change in sight. That’s when I really started to break in my moccasins as an activist. I prepared for the march for a whole year, but on the fourth day of walking, I collapsed. We held some ceremonies and I understood that the spiritual aspect had been missing. After that we conducted ceremonies every day, and I arrived in Ottawa feeling very strong.

MMIWG Inquiry Commissioners Michèle Audette, Marion Buller, Qajaq Robinson, Brian Eyolfson, wearing white – Photo courtesy of Michèle Audette

Jody Freeman: In your role as Commissioner for the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, were you in contact with families all across Canada?

Michèle Audette: Yes, it was in a very legal setting. I met with human beings in a legalistic context. I could have behaved like a judge—as an appointed commissioner, I could have worked in a setting that was cold and impersonal, not because of my biases but to be impartial. I wasn’t comfortable with that and had to be faithful to my own culture. My colleagues accepted that.

I would go to the families’ territory two days ahead of the hearings to meet with elders from the community, women, men and families, to partake in ceremonies with them so I could share their experiences with them. In each territory, I would take part in sweat lodges, pipe and tobacco ceremonies, sunrise ceremonies and visit the traditional sites that belong to our nations.

After the more formal part of the hearings, in the evening, our little Québec team would go and visit organizations that work for people who have lost a loved one, or people who are homeless, grappling with addiction, or working in the sex industry. In all the cities we visited, I went to meet with volunteers and spend time with people.

The community made it possible for me to open doors. Sometimes people would show up at 4:00 am or at midnight, because a body had been found. Sometimes my colleagues from the federal or provincial civil service were shaken up by all that, but I’d say “That’s why there’s an inquiry. When you’re back at work in your government offices, don’t forget them. They are real human beings.”

Jody Freeman: You are also working to address the roots of violence against Indigenous women, tied to the violent colonial takeover of Indigenous lands and plunder of the earth. And women are closely associated with the earth.

Michèle Audette: There is a film about Colten Boushie by Tasha Hubbard at the National Film Board, called We will Stand Up. It talks about everything you just mentioned. Because we were the First Peoples, people of the earth, whose conception of life was circular and interdependent—our relationship with animals, animals’ relationship with the earth, the earth’s relationship with us, with water, etc., our human interdependence—this healthy interdependence and natural reciprocity (“thanks, I’ll take some and give you some,” “nothing belongs to me, each of us takes and receives in a way that is respectful”)—all that was flouted and violated. And there, we see one of the major effects of destabilizing the balance between women and men. Colonialism is the No. 1 source of what I heard and witnessed during the National Inquiry. Colonial violence and religions— the role of women was denied to the point where we were not even human. […]

Jody Freeman: After the death of Joyce Echaquan, you travelled to see her family in the Atikamekw community of Manawan.

Michèle Audette: Yes, the day after she died. I went to her funeral with my daughter.

Jody Freeman: Joyce touched a lot of people, in her despair and courage. Like George Floyd in the US.

Michèle Audette: Yes, and her death reopened deep wounds and rage. She exposed the status quo [of ongoing systemic racism] that we’ve been denouncing. [Until her video, there was] total denial: “Racism is a problem in other places, not here. We’re ok here.” After that, it takes a lot to stay calm.

At her funeral, if you could have seen her husband and family… the resilience, the silence. We were all in silence. No one even cried out. […] Joyce’s husband told me, “Madame Michèle, it’s not over. We’re going to fight. Thank you for being here.”

After the funeral, my university wanted to honour Joyce on December 1, 2020, with her husband present. Its action plan entitled Université Laval en action avec les Premiers Peuples (Laval University in action with First Peoples)—and the major shift it embodies—is dedicated to Joyce and to all the silent voices that Joyce represents.