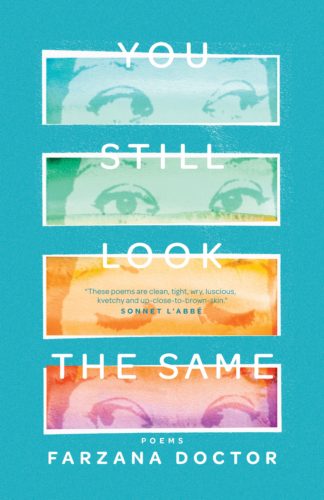

In Farzana Doctor’s first poetry collection, each of the four parts is entitled Therapy Homework, with a different exercise and a haiku response. Part I’s exercise is “describe your world ending in as few words as possible” and the haiku is “One day we left home, / forgot to lock the front door, / a terrible mistake.” And between the homework exercise and the haiku is a narrow illustration – just the poet’s eyes, in Part I, closed.

Most of the poems in Part I refer to breakups: hers, the neighbours’, friends’; everyone is hurting. In “Revisit,” after thawing and eating some old soup her ex made, which makes her ill, “I clear out the freezer, / chip away, two years of ice.”

Breakups are hard, but it’s not until the eighth poem, “Blame it on childhood 2,” where we witness the 11-year-old child trying to behave appropriately after her mother dies, that the introductory haiku makes sense. The “terrible mistake” is the death of the poet’s mother at the comparatively young age of 38, which seems to have made Doctor uncertain in the managing of her subsequent life.

“Fall back” presents her and a friend in a sweaty club the Saturday night the clocks go back. The friend urges her to enjoy the extra-long party, then asks “what if / this hour is a silver locket / holding every shining wish?” And Doctor knows how she’d rather spend the time: visiting with her dead mother.

In Part II the therapy homework assignment is “describe the process of middle-age self-searching in as few words as possible.” Illustration: her eyes look to her left. Haiku: “One airline ticket, / two years of online dating, / but what did you find?”

Frustration – sexual, emotional and just plain old trying to get things done – seems to be the theme here. Love and lust make their appearances, as does the bureaucracy at a New Delhi university where she tries to get permission to access the internet. It takes two hours, and after the next two years lead to dead ends, she just gives up, all her desires unfulfilled.

Part III: “describe trauma and its sequelae in as few words as possible.” Her eyes look to her right. “Ask me in two days / if I’m really okay. / Delayed reaction.”

In several poems love is a bad dream, something she does and does not want, and she wishes that she had better boundaries. In the poem of that name, “Boundaries,” she covets the boundaries someone else has, that are “stretchy yet firm / holding you in / keeping tendons warm / injuries protected” whereas her boundaries are useless as old band-aids.

Depression, especially in winter, appears in “Some days are like that.” Race is discussed in “Rockette lines on Queen West,” where she wonders why white people don’t have racialized friends, and in “Dear Jibon,” in which she is the recipient of a single-word message online – hide – which she takes to be some white supremacist warning her and people who look like her.

She sums up in “Perimenopause,” “body simmering / in forty-odd years / of bullshit.” And some of the shittiest of the bull is presented in “A Khatna Suite,” five poems about Khatna: female genital cutting practised by members of the Bohras, a Muslim sect.

“Zainab” is from the point of view of the person who’s been cut. She feels diminished. In “Rumana,” the viewpoint is that of a female doctor who performs the rite/surgery for the seven-year-old members of her sect. “I hand out lollipops / so it’s less frightening.”

“Grandmothers” calls out the women who make sure their daughters and granddaughters comply. “Twitter Trolls, aka, Bohra Women for Religious Freedom” – well, the title says it all. Not quite. Doctor takes the trolls’ online comments and stacks them in the form of a pyramid, the shape of the lost clitorises.

Thinking of all those seven-year-old girls, I repeat Part III’s haiku. “Ask me in two days / if I’m really okay. / Delayed reaction.”

The therapy homework in Part IV asks her to “describe healing and recovery in as few words as possible.” Eyes forward, looking at us, but still not completely facing us. “Then, out of the blue / you followed me on Twitter, / I no longer cared.”

Doctor revisits her theme of frustration with the limits other people impose because of race and gender. In “The beauty of us” she remembers being called a Paki at school and her mother’s going to the school to defend her. As a child she resented this attention being brought to her “shame,” but now as an adult she can see her mother in herself in a good way.

In “Nikah mu’tah” (a rite of temporary and private marriage), while participating in same at a mosque, she has to sit upstairs, invisible in the women’s gallery, away from the man she’s marrying. And in “Aging,” she claims kinship with all women who age, concluding with this:

Oh! let’s move

out of the city,

plant gardens,

strawberries and lilies,

grow out hair

wild and grey,

our gazes

our mirrors

and we’ll believe it

when we say

you still look beautiful to me.

Amen.

At the end of the book, the language of the poems starts to loosen up, become imagistic, rich. In “Sky in my veins,” in a dream Doctor sees fish in her arm bone, “just beneath my skin’s surface, / my forearm a spy hole into / an aquarium.” And leaps to “I awoke unafraid / for if there is an ocean / in my limbs / there must be / sky in my veins.” Nice.

And “Find me” is an amusing riddle-poem which leads one off of transit at the end of the line to what I guess must be – but that would be telling. The metaphor is one of freedom. “When the asphalt ends / yes, right here, slip off sandals / step barefoot onto sharp grass / lose your balance…” and that’s where I’ll end my quote.

In the book’s last poem, Doctor concludes that with her memories and books, she’ll never be alone. The “terrible mistake” of her mother’s death has been processed; solitude no longer holds any terrors for her. The therapy has been a success.

More about Farzana Doctor (from her official bio)

Farzana Doctor is the Tkaronto-based author of four critically acclaimed novels: Stealing Nasreen, Six Metres of Pavement, All Inclusive, and Seven. You Still Look the Same is her debut poetry collection. Farzana is also the Maasi behind Dear Maasi, a new sex and relationships column for FGM/C survivors. She is also an activist and part-time psychotherapist.