L’humanisme est la seule – je dirais même la dernière – résistance que nous ayons contre les pratiques inhumaines et les injustices qui défigurent l’histoire de l’humanité.

Humanism is the only, and I would go so far as to say, the final resistance we have against the inhuman practices and injustices that disfigure human history.

Edward Said

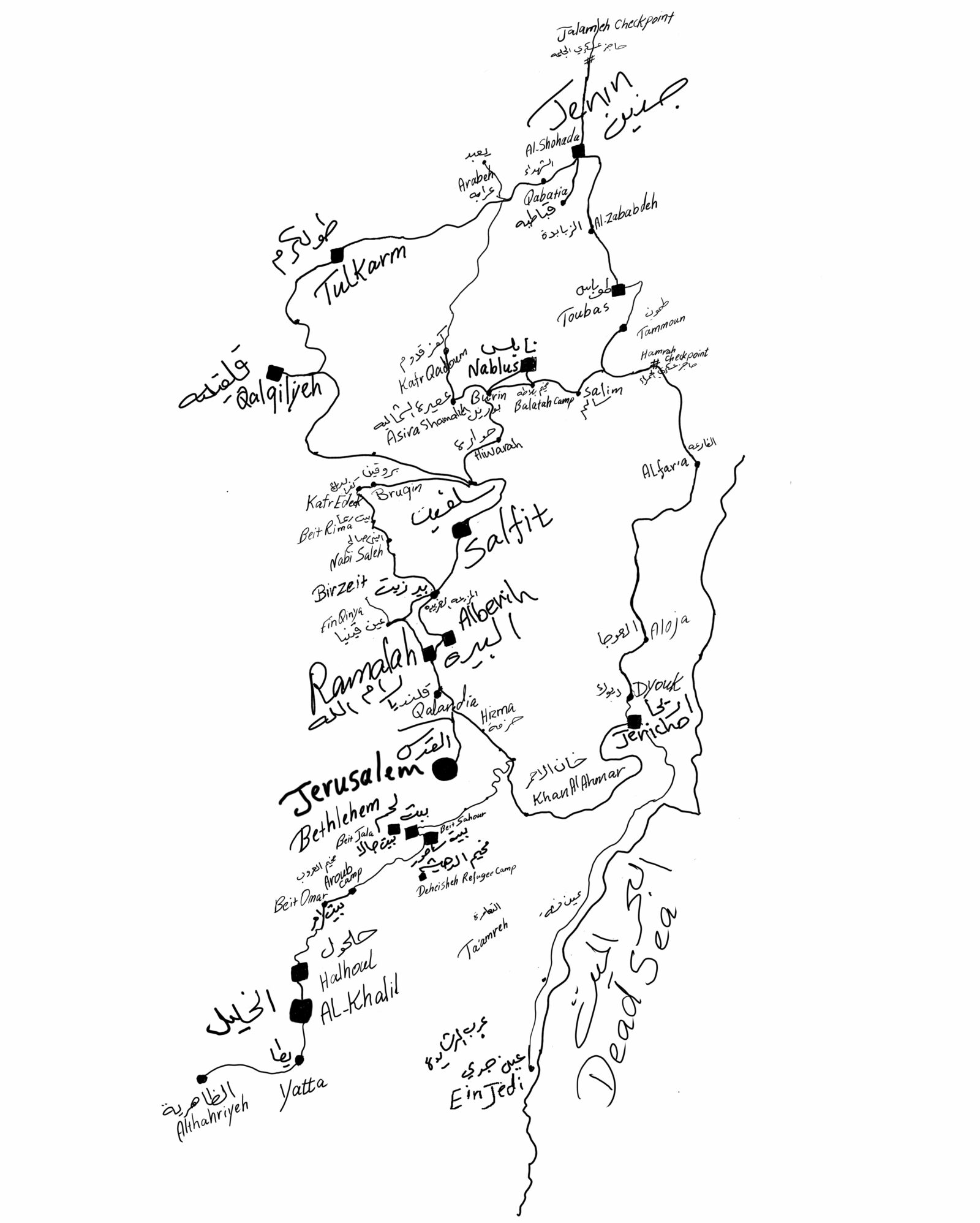

The theme of driving in Palestine is elaborated by Rehab Nazzal in a visual distillation of over two years of research and direct documentary-genre video and photography spanning a decade. The exhibition yields a profound examination of mundane dislocation, along with a deep sense of alienation evoked by the architectural photographic surveys and the active video sequences that “narrate” the impediments and obstacles to circulation and travel between Gaza and the occupied territories.

We are drawn to contemplate the philosophical aspects of opposing claims of land and territory to the simplicity and enduring strength of nature.

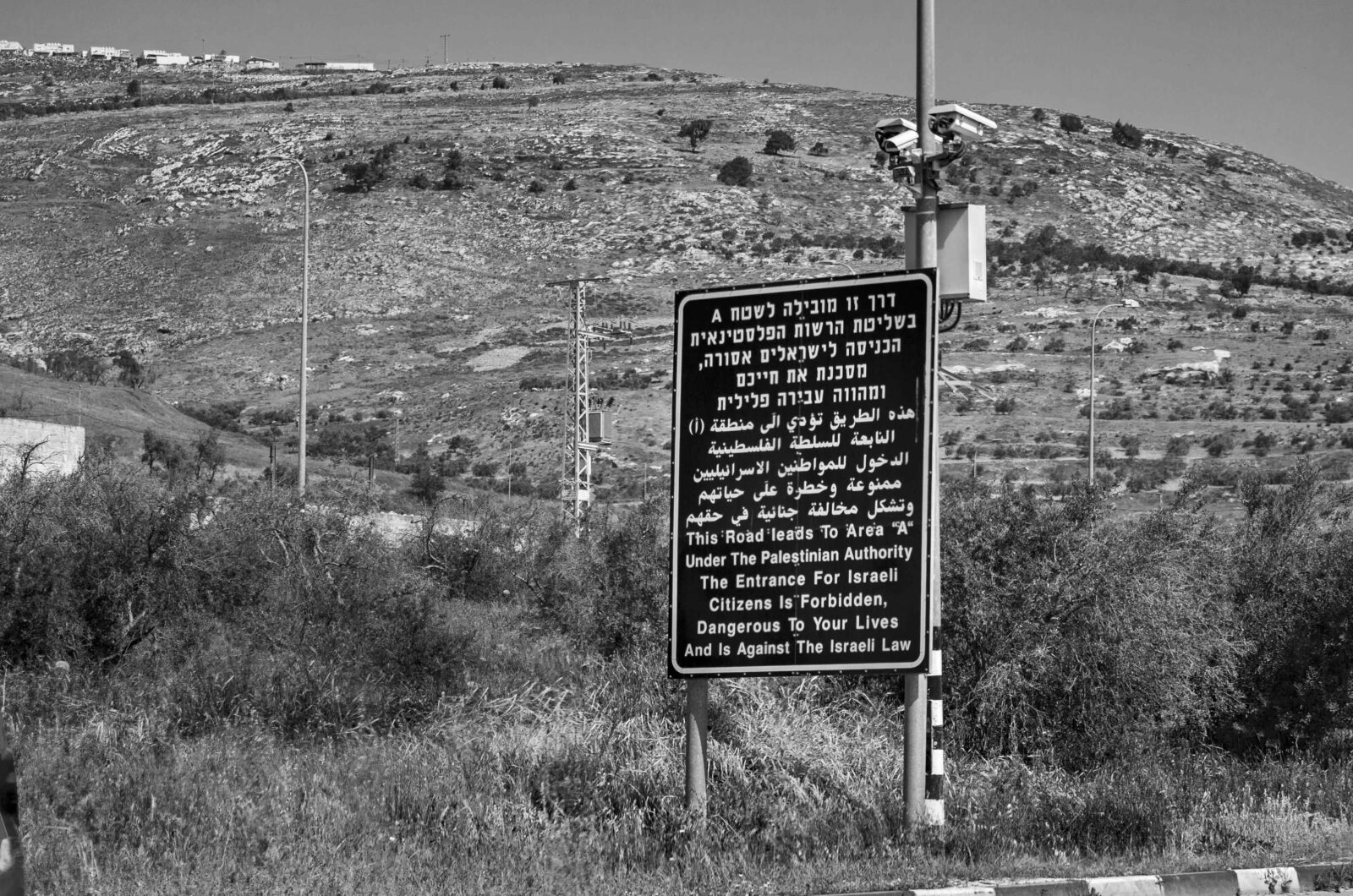

The visual landscape and concrete horizons are nearly devoid of any human presence, yet witness the marginalized experience of a life relegated and subjected to the control and machinations of an apartheid environment.

What is engendered is a culmination of brutal scarcity and oppressive atmospheric sentinels: sentinels of light, shadow and monumental barriers. The photographic architectural frames are presented in a serial wall mount. The unique traits of each wall surface, tower or militaristic building become signatory of the omnipotent as a collective presence, as one views the spectacle of oppression.

Void of colour, the sense of an impermeable orchestra of light and line delineates the confines of the all too real edifices that are the manifest occurrences of an architectural gulag. The static photographic realm, coordinated with great visual dexterity and minute detail, is counterbalanced by the vivid depictions that unfold in live video sequencing on the adjacent independent screens.

The video works alternate with and reiterate the imagery of the still images – signs warning of the dangers of trespassing, breaching protocol or otherwise deviating from the circulatory restrictions imposed by the Israeli apartheid state on Palestinian citizenry. As the imagery suggests, while seen only briefly, the installed signs dictate the literal trajectory of denizens of the region. A more animated and labyrinthian effect is created in a video that demonstrates, with a mild, near-mute soundscape, the actual experience of a tour by vehicle. Shadows of pedestrians and distant intersections, random laneways and streets reveal in a casually indirect visual narrative what life is like when aiming to depart from point A and arrive at point B.

As the driver aligns with the wall and proceeds along its symmetry, we witness the documented randomness of spray-painted protests, the evidence of razor wire and the heat radiating from the scorching sun on the bare concrete barrier. For those unfamiliar with the renowned division(s) of the Palestinian and Israeli territories (in terms of both statehood and physical boundaries), these images form a stark and formidable declaration. The alternating static and visually dynamic mediums impregnate the visual experience with a spatial reflection on the veracity and visceral reverberations of enforced state oppression.

Cinematic and photographic, spatial and visceral, the creations resonate with the quality of the punctum, as ascribed to the photographic image by Barthes. The lyrical intonation and retrospective candour entwine, juxtaposing an aesthetic imagery with a situational ethos void of poeticism. The presence of the imagery pays homage to the concept espoused by Joseph Beuys, that “To make people free is the aim of art, therefore art for me is the science of freedom.”

The question exists as to how best to manoeuvre within the limited confines of a space in a geo-political zone far from the original site of capture. And how best to free the perspective of those in attendance when one undertakes a mnemonic venture to illustrate a reality as brutal, intense and unsparing as this.

In this respect, the artist has employed a technique that highlights the absence of pedestrians, of citizens ensnared in the self-perpetuating demise of hope. The barren concrete, ashen-gray structures, and architectural scenery demand that our ocular focus (including our conscious or subconscious response) be embedded in the diaspora reflected in the still frames. The circuitous tedium and positioning of the moving images in the gallery’s hall conflict spatially and thematically with the grain and texture displayed within the static imagery. There is nothing accidental or puzzling about it: the polemic has become one of medium, while the content of the message bespeaks an eternal and enduring suffering. Absence is not confined here to compositional elements; it manifests as a thematic continuance.

Rehab Nazzal creates a performative intervention, where members of the public are invited to select and take printed images at the time of their visit. The large-scale photographs the size of posters serve as an equivocal echo of a mode often used in protest. Instead of flags or slogans, the public is free to take and circulate her visual messages, give them to others, and paste them on whatever urban surface they choose.

Related articles

The gift of imagery by the artist serves to disseminate the content, making her archive more interactive and relocating it to random junctions or stations across the Island of Montreal and perhaps beyond. The accent is on transition and juxtaposition of context: seeing the word “Palestine” spray-painted on the actual site of a towering concrete wall of Gaza, witnessing the photographic evidence on display in a gallery and carrying the image in hand to whatever final resting point one chooses leaves an indelible impression, both in cognitive and social terms.

The exhibition avoids any literal expression of condemnation. It offers an essentially documentary oeuvre: there is no conjecture, rhetorical device or propagandist retort. A visual forensic examination is at hand, and a conscientious one. On one lone screen, partially divided from the collective visual experience of the installations, a long sequence appears, showing blossoms, fields, soil and stone. The vista offered by the artist invites us to ruminate on the beauty of the land that could once again be restored should a peaceful accord be possible.

The serenity of nature is instilled in the viewer. We are drawn to contemplate the philosophical aspects of opposing claims of land and territory to the simplicity and enduring strength of nature. The title of the work, “… Healing,” imbues it with a powerful wisdom. It is a poignant epithet to the artist’s agon of direct documentation, tribulations and trials that echo those of her people. In Rehab Nazzal’s work, the testimony of a temporal witness is disseminated without mediatic travesty: with rigorous veracity, the documented experience eschews the commonplace of oppression.

It is impossible to disassociate the current war from this work, a creation which predates the Hamas attack on Israel, and Israel’s retaliatory onslaught against the Palestinian people. Rehab Nazzal’s creations were intended to bear silent witness and be shared with those who live far from the self-perpetuating conflict. Nonetheless, the latency of oppression, the stagnation of free movement, and the enforced barriers and architectural “might’’ of the apartheid practices of Israel are distilled in this brief visual chapter in a historically entrenched game of divisive rhetoric and violent intervention. Should we hear screams of terror and cries of mourning, or witness the fragmentation and collapse of buildings and structures within seconds of airstrikes, the works would be no more poignant.

In a sense, the exhibit avoids the pornography of misery and stands as an integral whole, without the brutal conflagration of voiced despair, dissent and revolt. The silence of the work appears more profound and more apt to elicit meditative reflection than the agitational propaganda that has inundated us since the outset of the war. The works of Rehab Nazzal attest to a rather more lethal manner of oppression: the gradual erosion of the essential core of a people’s survival and wellbeing.

Where a linear time sequence or historical reading is nowhere present, we are left to remain focused on imagery captured through clandestine efforts, and on a simultaneous experiment to recount and portray the prevailing mood and atmosphere. Signs warn, barriers of concrete divide, and the shadows of razor wire and ruins denote the submerged violence waiting to erupt. Rehab Nazzal’s exhibit is not prophetic – violence has been as common and predictable as the course of the tides. Although the source is often invisible, the waves of violence continue to erupt.

The region is once again wracked by death. What inspired the documentary works has now vanished, and we shall soon be left with the ruins of architectural evidence and destroyed urban and rural areas to attest to the current demise of a civilization, unless the war is ended and a ceasefire and peace are achieved.

MAI’s description of the exhibit

“Palestinian-born and Montreal-based interdisciplinary artist Rehab Nazzal employs a variety of media to examine the devastating effects of settler-colonial violence on the Palestinian people, land and non-human life. Driving in Palestine is a multimedia installation that combines photography, video, printed matter and sound to offer glimpses of Israel’s structures of segregation, confinement, surveillance and restriction to freedom of movement that proliferate the occupied West Bank.

Captured from moving vehicles on Palestinian roads spanning 2010 to 2020, a decade of images compels viewers to question the link between suppression and debilitation of Indigenous people and the attempts to expropriate and destroy their land. Nazzal’s work reveals a regime that suffocates, surveils and controls the Palestinian’s mobility within and beyond their territories. It invites viewers to witness manifestations of this regime including the apartheid wall, military checkpoints, gates, fences, watchtowers and roadblocks that Palestinians have had to navigate for the past 70 years.” MAI