“Poetry’s appeal is rooted in emotion. It tends to chase people away whenever it becomes too cerebral.” Michael Fraser

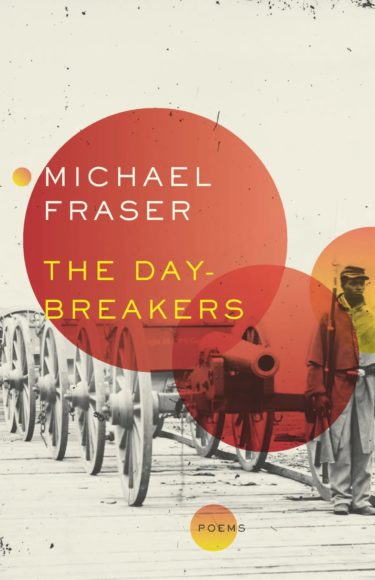

Author Mayank Bhatt interviews award-winning poet Michael Fraser, whose third collection of poems, The Day-Breakers, was published by Biblioasis in April 2022.

Mayank Bhatt: Michael, I’m interviewing you after five years. The last time was when your second collection of poems, To Greet Yourself Arriving, came out, and now we are chatting when your third book The Day-Breakers has been released. How have you evolved as a poet in these last five years?

Michael Fraser: Interesting question. There’s been a major personal upheaval, namely, my divorce, which I’m certain must have impacted my poetry; however, I’m not certain how, as it’s still relatively new. I’ve also latched on to many new writers, many of whom happen to be American, and I’m certain (that) devouring their work is influencing my style. I believe my style has become more lyrical and the poems aren’t as tight. I still pay close attention when editing; however, I’m no longer trying to diminish definite articles and religiously severing adverbs to the extent I did in the past. Coincidentally, I’m actually more efficient with my initial drafts, which obviously minimizes the need for extensive editing. Perhaps I’m becoming more sagacious with my incipient drafts. I’m still very confessional and narrative in my work. I think this is essentially who I am intrinsically as a poet, and this confessional element will most likely remain for the foreseeable future.

This question is in two parts – both connected to your profession and your day job.

Would you say that your experience as a teacher has influenced your choice of subject for the last two collections? To Greet Yourself Arriving was about North American icons of African descent, and The Day-Breakers is about unknown African-Canadian soldiers who fought for the Union during the American Civil War.

Also, your knowledge of African-American and African-Canadian history is a clear influence, as is the deep reading and immersion in Black poetry.

You acknowledge the influence of Bryan Prince and his book, My Brother’s Keeper: African Canadians and the American Civil War, and Richard M. Reid and his book, African Canadians in Union Blue: Volunteering for the Cause in the Civil War.

The titles of both your books are from poems by renowned poets: Derek Walcott and Arna Bontemps.

My experience as a teacher has not influenced my choice of subject matter for the last two collections. The subject matter has its genesis in my natural curiosity about the Civil War. I was interested in similar topics prior to becoming a teacher and I’m certain these interests will remain potent long after my teaching career. Again, these interests are integral to who I am. The seed of The Day-Breakers arose from my obsession with the Civil War and discovering that African Canadians actually fought for The Union. This little-known aspect of African-Canadian history arose from researching the Civil War in general and African-American (Coloured) troops specifically. War has interested me since childhood. When I was four in Grenada, I witnessed the army extinguish a demonstration in our subversive area. Soldiers jumped out of a truck, beat people and even cut one person with a cutlass (machete), then they piled back in and drove away. These images are ingrained in my memory. I believe this event is the source of my fascination with war as it’s one of three memories I have before age five.

My experience as a teacher has influenced my subject matter in general because I’m always cognizant of the topics I’m addressing, as I should be as a teacher. There are subjects I will never broach, and by extension, I’ll never use profanity.

I’ve always felt book titles should reference or allude to other works regardless of genre or art form. It helps to frame the book and provide readers with obvious external connections they can utilize when they immerse themselves in the pages.

If you recall our conversation when your second book was released, I had observed that you retain your sensitivity even when your poems are overtly political. At that time, you had made an interesting point – of there being racism within racism – that your book won’t have Muhammad Ali but will have Joe Frazier. Is that what motivates you to portray the life and struggle of these characters who are known only to historians who study Black history?

I possess an adamant and unrelenting desire to cheer on and support the underdog. I believe this is partially due to my diminutive stature and being a darker-skinned black person. There are hierarchies within every “group.” This has always annoyed me. I’m dark-skinned and my brother is light-skinned. I was consistently reminded of this discrepancy in shade. Colourism is rampant in many visible minority communities and many of us with darker skin were often considered less attractive (less intelligent, etc.) and even told this by family members and members of our visible minority communities. Ali had a fairer complexion than Frazier and he leveraged this whenever he called Frazier “ugly” and a “gorilla.” Even as a child, I felt Ali was calling me a “gorilla,” especially since I was the darkest one in my family. I always cheered for Frazier.

The issue with Black Canadian history and Canadian history in general is we’re overshadowed by the United States. I would venture the average Canadian knows far more American history than Canadian. This is heavily amplified with regards to African-Canadian and African-American history. There’s complete cultural and historical hegemony from the U.S. Think about it. Many Canadians view Canadian films as “foreign films” and Hollywood as partially Canadian.

African-Canadian history needs to be championed, and the lives and struggles of these African-Canadians who fought in the American Civil War must be known beyond a handful of scholars. I’m pleased that I’ve brought their lives to the fore in this poetry collection. If this means an additional hundred people are aware of their lives and contributions to both American and Canadian history, then I’m elated!

You won an award in 2016 with your poem “African Canadian in Union Blue.” In the subsequent essay that you wrote, you said you practically churned out the poem in three hours, and didn’t have the time to even check the line breaks. Actually, the absence of line breaks turns a part of the poem into prose, and it enhances both its appeal and accessibility. Would you agree? And, if you did have time, would you have reworked the poem to make it read and look different?

Yes, “African Canadian in Union Blue” won the 2016 CBC Poetry Prize, and I literally wrote the bulk of the poem three hours prior to the contest deadline. However, the first five or six lines of the poem were initially penned roughly a month earlier. I could have added four or five more lines, but I’ve always followed Hemingway’s advice regarding the subconscious and writing. He said, “always stop while you are going good and don’t think about it or worry about it until you start to write the next day. That way your subconscious will work on it all the time. But if you think about it consciously or worry about it, you will kill it and your brain will be tired before you start.”

I’ve followed this advice for over 25 years and I find it highly beneficial! Also, the elusive poetic muse (or my subconscious on warp speed) was the main contributor. I literally heard a stream-of-consciousness voice emerge and provide me with the poem at that three-hour mark. It was truly other-worldly. These poems that seem to materialize out of thin air are often the best poems. Yet I’m certain my subconscious was piecing it together for the full three weeks prior to the poem’s revelation.

I don’t think I would have reworked the poem if I’d had time. These poems that are “gifted” to us rarely need much revision. The stream-of-consciousness style and rambling cadence of the poem is perhaps its greatest attribute; any heavy revision would have disemboweled it tremendously.

In your latest collection of poems, you expect the reader to do research on the subject to be able to enter your world and enjoy the poems better. I mean, I was completely unaware of the subject – of the role of African-Canadians in the American Civil War – and had to do some secondary research on the subject so that I could enjoy the poems better, having understood the context. Do you agree that poetry has evolved to become more cerebral rather than just appeal to the readers’ emotions?

This is a compelling and erudite question that required much contemplation. I don’t expect the reader to do any research. My only expectation of a reader is to read the text and immerse themselves in the poems. The magic of a text’s meaning doesn’t occur until a reader interacts with the text. The reader unlocks and simultaneously invokes the text. Each reader is different, and as unique as fingerprints. Their reading experiences are also unique and reflect who they are as readers and all the previous life experiences, knowledge and personality they bring to the text.

Your desire to partake in secondary research on the subject matter illustrates who you are as a reader. Every reader will approach historical aspects of the poems in their own personal ways. This is continually confirmed by people’s reactions. Different readers have focused on different aspects of the poems. Many have positively commented on the unique lexicon. I specifically included a glossary of terms to ensure the uncommon jargon isn’t an impediment for readers. Also, the poems are heavily written in the first person, which lends a confessional narrative element to the poems. I’ve also taken tremendous poetic licence with historical facts. Essentially, this is a book of poems set in a particular historical period, as all things are, but it’s not a history book.

I don’t agree that poetry has evolved to become more cerebral, rather than appealing to readers’ emotions. The range of poems, reading series, poetic journals, poets, poetic styles, etc., is vast, and seemingly ever-widening. I was part of a reading last week that literally included 10 poets reading for roughly 10 minutes each. Audience members were exposed to everything under the poetic sun stylistically, from rhyming formalist poetry to spoken word, confessional poems, etc. The subject matter was even more varied. There were certainly no “L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E Poets” or anyone riffing poems about semiotics in the group.

There are journals that obviously cater to cerebral material, but their numbers are few in the poetic universe, even in institutions of higher learning. I actually can’t recall the last time I heard such material. Poetry’s appeal is rooted in emotion. It tends to chase people away whenever it becomes too cerebral.

Michael Fraser is a Toronto poet, writer and high school teacher. His first book of poetry, The Serenity of Stone (Bookland Press, 2008) delves into life in Grenada, Edmonton and Toronto, with a hip hop twist. His second collection, To Greet Yourself Arriving (Tightrope Books, 2016), offers poetic portraits of historic figures from Rosa Parks and Harriet Tubman to Oscar Peterson, Jean-Michel Basquiat and P.K. Suban. The Day-Breakers (Biblioasis, 2022) pays homage to African-Canadian soldiers in the American Civil War.

For more information on Mayank Bhatt’s life and work, please visit his website.