Jocelyne Dubois’ latest book of poetry, Memorial Suite, is a beautiful, haunting work, written in a style uniquely her own. In some ways, it can be seen as a complement to her novel World of Glass, which followed the struggle of a young woman with bipolar disorder as she sought to extricate herself from a world of alienation, pain, terror, medication and mental health facilities, and return to the joys of normal life, tranquility and love. While the novel deals with the structure of this long and difficult path, however, the poems zero in on particular moments, people, moods, and sensations from a more intimate and immediate point of view.

Dubois deftly uses everyday language to reveal the transcendence of human experience, exploring the power within the details of life. Maxianne Berger and Carmelita McGrath, whose insightful commentaries grace the back cover, point out the lyricism of her “clear,” “spare” lines, written in a direct, objective language that goes right to the core of each poem. Dubois’ work is fundamentally autobiographical, but what difference does it make if the characters are actual people or are fictions in themselves? The symbolism that emerges from them may have been lived or invented, but it is real in every sense.

Reading these poems, I was reminded of the transparent, informal style of William Carlos Williams (a physician himself), which often contained many more subtleties, connotations and ambiguities than more florid works of the time. Dubois’ lead poem, “Hot Summer Night,” is a delicate mosaic of action and feelings, with an oblique, suggestive eroticism — “My body perspires, I desire” — that lets the reader draw the connections rather than point them out directly. The eloquent last three lines of the poem then move into a moment of revelation that uses the images to take the poem far beyond, to an existential realization, giving them the impact of the final stanza of a Renaissance sonnet, which in fact the structure of the poem resembles: “I cannot wash off what is perfect, what/ shines like crystal, something more than wind/ stronger than rain, more solid than stone.”

Dubois is an expert at powerful end lines, often with a final word or image that flips the objective body of the poem onto an unexpected, ironic plane. The speaker in “Reproduction” lets her pregnant sister take her hand and pass it over her curved belly at the same time as she is eating salad, and comments that “when I leave I leave hungry” (space intended). In “Words,” a woman speaks of her difficulty in returning from the numb realms of medications and psychiatric wards to the world of conversation and connection so that she can “know precisely/ what not to say.” And in “The Lady Upstairs,” the speaker’s neighbour, an elderly Slovak woman who lives alone, shows her photos of her family, children and grandchildren who live in Texas and whom she calls every few days: “‘They say I love you, I love you’/ she tells me,” and the last stanza: “Christmas card from her family/ propped up on her kitchen table/ unsigned.”

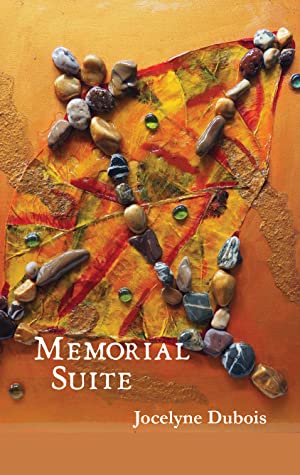

Jocelyne Dubois is also an accomplished visual artist, who has exhibited her work in several galleries in Montréal. She specializes in palimpsests of painting, cloth, leaves or other mixed media, and designs of coloured pebbles, all covered in transparent varnish that holds things in place. The remarkable cover of Memorial Suite, with its intersecting and broken lines of stones, is one of her works, and all three sections of the book begin with black-and-white reproductions of other paintings, each of which is a reflection on the text, from the pearly aspect of “Hot Summer Night,” to the vertical rows of stones like corn kernels in “Memorial Suite,” to the swirling, free flow of forms in “A Second Chance.” These three sections chart the path of her life, from her early years on her own, through her breakdown as she struggles with bipolar disorder, and on to healing, falling in love and marrying.

Many poets, such as William Blake, have been painters, and many painters, such as Francis Picabia, have been poets, though perhaps it’s better just to say that they are artists who express themselves in several mediums. Dubois’ visual work has interesting parallels to her writing: the stones, arranged in different forms and chosen in particular colours, bring to mind the people she describes, always elevating the common to artistic recombination and a search for meaning. In the poem “Colours,” the speaker writes of her intention that “When I die/ I will donate them to a psychiatric hospital/ where walls are eggshell & bare/ […] to bring sun/ to those locked up.”

The title of the book undoubtedly alludes to many memorials, but principal among them is the Allen Memorial psychiatric hospital, perched on the side of Mount Royal, originally the home of a shipping magnate who named it “Ravenscrag,” and known in the 1960s for the clandestine CIA experiments in mind control that took place there. Dubois opens the second section of the book with a poem about it, contrasting the building’s 19th-century wealth and finery with the plastic chairs and styrofoam cups of the patients waiting there a hundred years later. The individual poems, several of which are titled “Jocelyne,” are portraits of patients, nurses and doctors: bare-boned word sketches of isolation, powerlessness and loneliness, in which her observations are like brushstrokes in a zen painting.

The author’s realism is kind, but doesn’t include either false hope or patronizing clichés: each person is unique, with their own hopes and delusions, stuck in a mental paralysis between illness and medication, or ill-tempered from working there too long. Writing is her liberation. It carries her through her isolation and finally into the gradual, longed-for recovery of the last section of the book, in which rigidity and loneliness fall away as she reconnects with people and the natural world, where colour, music, laughter and pleasure return, giving her a renewed life of surprise and serenity and filling the reader with joy and relief.

As I finished reading Memorial Suite, I was reminded of the words of Allen Ginsberg’s mother, who struggled with mental illness and confinement, in his poem Kaddish: “The key is in the sunlight at the window.”