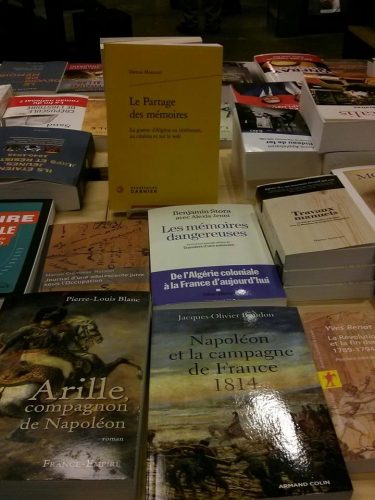

Le Partage des Mémoires by Djemaa Maazouzi, Classiques Garnier, 2015, 487 pages

Montréal in 2016 is a vital mosaic of neighbourhoods, ethnicities, events and people. This urban variety encompasses many outstanding individuals, and one of them is a woman named Djemaa Maazouzi. With a doctorate in French literature, she teaches French at Montréal’s Dawson College and her background includes both Algeria and France.

Djemaa Maazouzi’s research in universities in Canada and France has centred on collective and individual memories of momentous events, and in particular, the Algerian War of Independence (1954-1962).

She draws on academic work developed over the last generation that makes a distinction between historical analysis and the restless energy of recollection, which she says is ever-present, dynamic, and more highly charged emotionally. Her recently published book is entitled Le Partage des Mémoires, which roughly translates as “The Sharing of Memories.” The plural is important here, because Maazouzi believes that traumatic events like the Algerian struggle with France leave behind what she calls a “polyphonic” and dialectical interaction of many different memories intersecting in various explicit ways that are nonetheless unconscious and invisible.

Maazouzi’s goal is to bring these patterns of recollection to the surface of our consciousness in the aim of furthering solidarity among those she calls “bearers of memory,” enabling even former antagonists to see what they share in common.

To illustrate this process of recovering a deeper sense of the past, Djemaa Maazouzi looks at the work of three creative artists in France: Zahia Rahmani (born in 1962), a passionate writer and art critic whose father was a “harki” (a term used to describe Algerians who were in the French Army during the Algerian War); Mehdi Charef (born in 1952), a screenwriter and film director of Algerian descent; and Tony Gatlif (born in 1948), a filmmaker and writer whose mother was a member of the Rom minority in French Algeria and whose father was Algerian.

Le Partage des Mémoires is a powerful book that draws together all kinds of experiences – tragic, haunting, terrible, poetic, stark, searing and loving. Djemaa Maazouzi provides close textual readings and examines films, plays and videos on the web – all to create a vibrant, collective membrane of memory extending out to various dimensions. At one point in her book, she asserts that on the web there are constant and quickening pulsations of memories reverberating together in what she calls a “hypermemory,” which has been stirring French society for a number of years right up to the present time. All one has to do is Google terms such as “the Algerian War” or “pieds noirs” to feel the energy of this surge of recollection.

I tested this assertion of hers by typing in a few words on a search engine, and indeed found myself immediately visiting a variety of sites. CLICK – there was a website highly critical of the French forces in the Algerian War. CLICK – another praising the notorious parachute regiment that carried out much of the terrible torture during the conflict. One thread of memory led to another, just as Maazouzi claimed, and during a lengthy session of web searching I finally found myself looking at an interview with 92-year-old Henri Alleg (1921-2013). He was the famous French-Algerian communist and journalist who in 1958 published La Question, a book that documented the immensely cruel interrogation techniques used against Algerian freedom fighters by the French Army. There on the web you find an intelligent, decent and humane Alleg explaining that he still believes in his life-long ideal of a world without oppression.

In Le Partage des memoires, Djemaa Maazouzi mentions figures such as Alleg, but concentrates on her three principal creative voices – Rahmani, Charef, and Gatlif.

Using a legal metaphor, she shows that these artists are “bearers” of memories that mark particular phases: the trial of the father (often one’s own father); an encounter with the Other; and a subsequent “return” that often involves reconciliation with the land and history of Algeria.

Maazouzi begins with the writer, Zahia Rahmani, and her highly praised prose work, Moze.

Moze (2003) is a fierce book that tells the story of Zania Rahmani’s father, an Algerian Muslim who was part of the French Army – a “harki.” Rahmani remembers growing up in France with an intense sense of shame, since her father was considered a traitor by the new Algerian government after the war. He and others like him had been promised French nationality, yet when they and their families arrived in France, they were treated like utter outcasts and could only acquire citizenship after a slow and painful process. Her father’s name was Mohammed, but Rahmani gives him the cryptic made-up name of “Moze.” He was an immensely sad man who hardly spoke when he lived in France, and on Remembrance Day, Nov. 11, 1991, he visited a war memorial and then committed suicide. When her family first went to France, her father locked them all up – the mother and the two sisters – huddling with fear in their new place:

“In the beginning we lived in the dark. He locked the doors and the windows… He said to us, ‘You are nothing. Not exiles, not immigrants. You are nothing. You are not going to be French. You are nothing. Nothing. To be a harki is to be nothing… to live as this piece of nothing!’ He taught us to live with his pain.”

In the book, Rahmani judges her father and comments, “Is it not so, that colonialism feeds on the remains of humanity and mangled citizenship?”

Djemaa Maazouzi uses Moze to depict how, for people like Rahmani, memory is invoked to judge the father and find him guilty, but the crimes he is tainted with extend far beyond him. And Maazouzi the critic argues that in the novel, the trial of the father then also becomes the defence of the father, and the “trial” turns into the prosecution of colonialism itself. This dual trial, as Maazouzi describes it, is heart-wrenching and disturbing. Moze exhumes and resurrects the father in order to expose the costs of historical oblivion and bring to light the unspoken subtext of an entire community – “the unspoken (underlay) of French society,” in Rahmani’s words.

It is an extraordinary fact that for more than three decades, France never officially acknowledged the Algerian War. Described instead as “events” or “rebellion,” it wasn’t until June 15, 1999 that an act passed by the French National Assembly referred to it as “the Algerian War.”

Le Partage des memoires uses Moze to bring the invisible out of the shadows and into daylight. From there, Maazouzi goes on to examine the work of writer and filmmaker Mehdi Charef, and more specifically, his autobiographical film Cartouches gauloises (2007).

Charef is the son of an Algerian man who emigrated to France in order to work. Charef himself experienced the sorts of difficulties often encountered by creative adolescent immigrants in Europe. His deep love of cinema stemming from his early childhood in Algeria gave him a way to define and structure his world. His tough but compassionate outlook allowed him to connect with others and, through his truth-telling, to imagine what a real encounter with the Other might be like. Charef comments on the pieds noirs before independence, saying that “the Arabs were hungry, and they [the pieds noirs] saw nothing.” Yet he also explains that since his time in France, “I have discovered things in them (the pieds noirs) that we share, that have touched me and moved me.”

Djemaa Maazouzi uses Charef’s work to illustrate the type of encounters that are and are not possible between different kinds of memory – encounters that fail to take place and yet might succeed. Maazouzi suggests that these tensions that arise in telling, re-telling and communicating lie behind all of Charef’s films and writing.

The last person that Maazouzi uses to bring her own account to a close is the very well-known Rom film-maker, Tony Gatlif, the son of an Algerian father and a French Rom mother who lived in Algeria. Maazouzi focuses on the movie Exils (2004), which tells the story of a young man and woman who leave France to effect a “return” to Algeria. The culmination of the film is a Sufi-inspired trance that seems to be a metaphor encompassing the Mediterranean as a whole, all its memories drawn into a common vortex where binary distinctions disappear and merge into something far more basic, and universal.

Le Partage des memoires itself searches for clarity and energy that reveal various partial truths in an effort to move beyond them (or perhaps through them) to a broader solidarity. Djemaa Maazouzi ends her book with the assertion that “to lend words to personal experiences is a way of making the fragments of our own lives – fragments that we consider significant – both visible and comprehensible to ourselves and others.” Le Partage des mémoires does just that.