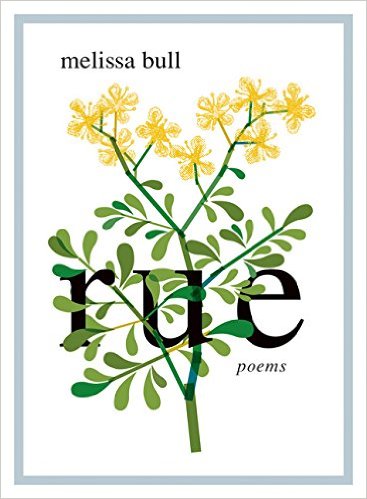

[Melissa Bull, rue, poems, Anvil Press, 2015, 104 pages]

I was handed a copy of Melissa Bull’s debut book of poetry, rue, less than a week after a meaningful exchange with a writer friend. Under late September lamplight, we walked along rue Jeanne-Mance in Montreal and I asked my friend about the impulse or intuition that fuelled his poetic endeavours. Why does he write? He struggled to answer and for five slow blocks we tried together to put our finger on it. How do words come to contain worlds? How do the associations that bind words to one another (in other words, meaning) bring about a sense of order and coherence in the vast unco-ordinated mass of experience? By what mysterious process do language and memory congeal as the idea of me? At the crossroads of word and thought, we pondered over equal parts literary and philosophical, recognizing that in these questions lay a sort of unknowable door leading to an even less knowable essence: the essence of what it means to be human.

My mind still full of the questions from my earlier exchange, I immediately noted a resonance between what my friend and I had discussed and Bull’s poems. I discovered in her lines something of an answer to our question.

Although answer is the wrong word. Rue offers no answers, does not presume to. Its authorial voice surfaces gently from a descriptive language sprinkled with neologisms (“Cheese curds fatsmear my agua de panela. Fatsmear fatsmear fatsmear”) and stylistic play that explore ways to convey most directly and spontaneously the encounter being retold, the sights, sounds, smells and impressions that form the basic ingredients of experience. The narrator never says “this is what this means.” She lets the connotations of the words, their inexorable tendency to reach out beyond themselves in search of connection, do the work for her.

The collection is divided into three parts. Brood offers fragments of the author’s parents and youth. In Skirting Petite-Patrie, poem titles are place-markers along a haphazard course through Montreal neighbourhoods, Boston, Bogotá, Saint Petersburg. Eloquent Areas grieves a father’s illness and death. Apart from the loose thematic structure of the three parts, little effort is made to connect the individual pieces. Each piece is instead left to stand on its own, a self-contained impression of places and people. Even the style fluctuates from poem to poem: from the abstruse alliterations and assonances of “Recipe” to the autobiographical narrative of “Bleeding Hearts” and “Claremont, Apt. 45;” from the evocative minimalism of “Fuse” to the verbose irony of “Nevsky Prospekt;” from the gentle rhythm and rhyme of “Arc” and the all-caps refrain of “BATTERMEDOWN!” to the matter-of-fact prose of “Scaffolding” and “Valentine.” The collection’s stylistic diversity is carried forward in Bull’s language, which although predominantly English, floats seamlessly into French on occasion (with a bit of Spanish), the transition marked only by the use of italics. The author is equally comfortable in both languages, both styles, both modes of engagement. Rue, a persistent undertone of bitter regret that marks the collection as a whole, is also rue: a city street, an exploration of memory and place.

Indeed, rue feels like a searching. A poet searching for her voice. A moment searching for the right word: the word that will capture it, convey it, recall it so vividly as to bring it to life again in the reader’s mind. Each new moment requires a new word, a newly affirmed level of engagement, an ability to listen. The eclectic diversity of rue is a testament to the author’s engagement and ability to listen. Its search is as much a search for a voice truly its own as it is a search for the right word, the word subtly beckoned by each new encounter.

Upon reading rue initially, my impression was that of a jumbled assortment of poetically rich sketches. There was no identifiable thread, no apparent consistency among the pieces. It was only once I had finished reading the book and put it aside, letting its contents sit for some time, that the poetry began to take effect, revealing itself as the complex portrait that it is. Rue is a portrait of a life, of an individual becoming. Its seemingly unrelated (and at times mundane) parts come together to form a me, a me more real than any consistent structure or style could ever achieve. Rue appeared before me not as an answer but as a testament to the questions my friend and I had pondered as we walked the streets of Mile End a week before. How do language and memory congeal as the idea of me? Like so. Rue doesn’t tell, it shows.

Underlying the heterogeneous feel of rue lies a restless unity, a thread of searching that evokes something profound, shared, human. Authentic. Melissa Bull’s artistic sensitivity and exploratory style have yielded a vivid portrait of a person, of the places and people that make up a person. Like all poetry, it demands much of the reader: time, patience, attentiveness. But for those willing to grant it these things, rue has a great deal to offer in return.