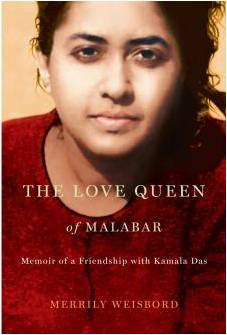

THE LOVE QUEEN OF MALABAR. Memoir of a Friendship with Kamala Das. Merrily Weisbord, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, 2010.

In order to understand why we should care to read the memoir of a friendship between two writers who were born in two different continents, we must first realize that Kamala Das left a gaping hole in the world of Indian literature when she exited this earth to hopefully attain the paradise that her conversion to Islam promised her.

Kamala Das was a poet, essayist, memoirist, short story writer and would-be politician who wrote fiction in her native Malayalam and poetry in English, the medium of her education at the hands of her great uncle, a renowned man of letters. Her father had been a journalist and her mother a well known poet. In 1984 Das was short listed for the Nobel Prize in Literature along with Marguerite Yourcenar, Doris Lessing and Nadine Gordimer. When she died in 2009 at the age of 75, throngs of Hindus, Muslims and feminists, who had alternately admired her and vilified her, attended her state funeral in her home province of Kerala, South India.

Merrily Weisbord is an award-winning Canadian journalist, filmmaker and broadcaster whose decade-long friendship with Das, several visits back and forth between the lagoons of Kerala and the Laurentian lakes as well as copious transcripts provide the material for this one-of-a-kind book.

What inspired Weisbord to undertake this circuitous literary journey? First it was Das’ work, which she found stunning, then her intriguing personality and finally the friendship born out of what prima facie appeared to be a contrived experiment in mutual revelation for literary purposes. Take a look: to begin with, Merrily receives a faxed-in love letter written by her companion back in Canada and reads it aloud to her friend. Then Das urges one of her lovers to profess his love to her in Merrily’s presence. Mutual revelations about their sexual experiences, motherhood and the writing process are encouraged and recorded. The writers follow each other around in their quotidian lives. Doesn’t the Heisenberg effect warn us that observation alone changes the behavior of the observed? But then this staged setup starts gathering momentum and art and life merge blurring the boundaries between both. Not that it matters because in the end the reader is caught up in this compelling narrative and cannot put the book down.

Kamala Das forged her English on the solid anvil of the classics but was considered uneducated because she failed in mathematics so she was married off at 15 to a man more than double her age. He was a homosexual, but by her own account, subjected her to sexual practices which she found distasteful until she gave him an ultimatum. “I want the freedom of my private parts”. With “permission” to be celibate she was able to write at night while the children slept in order to support the family during difficult financial times. Her highly eroticized poetry, her fictional denunciation of social ills like child abuse and her newspaper columns on anything and everything earned her a large readership, the opprobrium of a very traditional society, the admiration of feminists and the lustful fantasies of hypocritical males.

As Kamala and Merrily bonded like sisters in “the same tribe of writers” many of the poet’s contradictions confounded her friend. Kamala claimed to have suffered greatly at the hands of her husband yet in later years lauded him as her best friend and supporter. This might just have been true when she emerged as a well-known and highly respected writer which prompted her husband to act as her manager and protector until his death. She also claimed to dislike sex yet she was a devotee of Krishna, revered by Hindus as the embodiment of divine love in a human body.

Kamala Das’ boldest action was her conversion from her matrilineal Nair Hindu caste to Islam at the behest of a young Muslim lover with whom she fell madly in love at 65. Whether this young Muslim prompted Das to convert with the offer of marriage out of love for her or love for the one million dollars that the Saudi Arabians supposedly paid him (according to “a family friend”) is not clear. What is absolutely clear is that her apostasy earned her the disaffection of her family, death threats from Hindu extremists as well as from Islamists who forbade her to abjure Islam and return to Hinduism. It also disappointed feminists who view Islam as a patriarchal institution. Towards the end Kamala would admit to Merrily that religion was nothing but a garb to be shed when the time came. When her time came, she was buried near the mosque where she had converted to Islam. If there is an epitaph on her tombstone, it could well read as follows:

“First I will strip myself of the clothes and ornaments. Then I will peel off this light brown skin and shatter my bones. I hope at last you will be able to see my homeless, orphan, intensely beautiful soul, deep within the bone, deep down under, beneath even the marrow…will you be able to love me, will you be able to love me someday when I am stripped naked of this body… Ente Katha (Malayalam version of My Story)

Merrily Weisbord’s memoir of her friendship with the Love Queen of Malabar has not solved the riddle of Kamala’s many contradictions but it has achieved what she unambiguously wanted out of life: to be loved, not just as a writer but as a warm, courageous woman who dared to be herself.

N.B. This book provides a complete bibliography of her work in English and Malayalam and is liberally sprinkled with memorable quotes.