I’ve been thinking about the concept of dominant culture lately. Seen through the eyes of a child, I imagine it relates to a certain comfort zone, that of belonging, of being invisibly couched in what is the “norm.” It certainly is a big issue for children who emigrate to another country with their family. The need to belong, to not stick out, to become invisible.

“ENFANTS AU BEAUBOURG” 1989 © Máire Noonan

Within linguistics, especially bilingualism studies, this is a salient aspect in that it interacts with the speed and success of second (dominant) language acquisition, as well as with the complex relationship to the heritage language (i.e., that spoken by the family). Did I want to stick out as a kid, as a teenager? For sure. I assume many youngsters have a desire to be remarked in some way. In which way? I would say through some individualist feature: Are you pretty? Are you popular? Smart, quick witted, funny? Right clothes? (How I pestered my mother to buy me Levi’s, and not jeans from C&A for a third of the price!). I knew I had a funny laugh that people seemed to like, and I definitely played it out to my advantage.

All this is great. But note: What you don’t want is to stick out by something fate forced onto you. Examples: a birthmark on your face, a lame leg, a persistent phlegmy cough. You also don’t want to stick out because of what your heritage dealt you: features that depart from the norm, the culturally dominant sphere. For example, a “funny” name, a “funny” language, a skin colour different from the majority, etc. For a long time I wondered why I always felt such natural affinity with those that are racialized, oppressed, discriminated against, short, with “the other.”

After all, I am white and I grew up in Germany. My grandparents were adults during the Nazi time. My grandfather appeared to me as a tolerant, laissez-faire type of guy, a lovely gentleman who smoked Egyptian cigarettes, drank bottles of red and got some quarrelsome reactions for both from my grandmother. He had no terrible prejudices that I could detect (an avid Willy Brandt supporter is what I remember). My grandmother appeared the more prejudiced one. Yet, she was the one who had refused the Nazi party membership – he had not. I suppose he was a docile family father who only wanted his own ones’ peace.

Going back to my empathy with the “other,” I always thought that it was an overdrawn sense of culpability: I needed to protect the underdog, because my grandparents hadn’t. My first piece of fiction – a high school assignment – at age 13 or so – was about a Turkish boy. I don’t have the story anymore, but I remember it well. A Turkish boy, sitting at the edge of a field, a pocket knife in hand whittling away at a piece of wood, and thinking of all the insults that were regularly being hurled at him. How he was a “dirty Turk,” a Messerstecher (‘knifestabber’ – a then popular racial slur against Turkish males in Germany), and so on. The boy muses about all this and gets himself into a tizzy. His frustration and internal anger rise to a point where he suddenly becomes aware that he is, quite violently, stabbing at grass tufts around him. He pauses – aghast, transfixed in the realization of having temporarily become a creature of the type others insultingly called him (Messerstecher!). The story was, of course, naïve. What was worse, I actually knew no Turkish kids. That’s just it – I was growing up in a very homogeneous white, Protestant school. But if I believed my mother, it was well-written (and of course I believed her!). Yet I received a mere B+ for it (the German equivalent of it), while a fellow student, let’s call her Frauke, received the highest grade for some traditional sort of murder mystery. She got to read her story out loud. The class, or most of it, was awestruck. I remember resenting her and yet thinking, oh why couldn’t have I written something so perfect? (Later, some peers told me Frauke’s story was direct plagiarism of Arsenic and Old Lace! If true, well so much for that A+ she received!) My mother was quite annoyed when I brought back the graded short story. I remember her bemoaning the fact that a story revealing social conscience at an early age would not get more recognition. Again, I agreed with her, fully – ha ha!

I grew into a rebellious youngster who rejected all things German with a passion (except of course my friends, my family, much of German literature, food-related things, etc.). I was prejudiced, except, precociously, I considered it “post-judiced.” For how, I would argue, could I have prejudice against the culture that I was growing up in and that I knew so well? I caused all kinds of grief to my mother. I hurled insults at German cops (many of my peers were with me on that one). On one occasion, I brought my entire family and that of my aunt by marriage to tears. It was a big family event – the confirmation of one of my younger cousins. I did not want to go, but was coerced by my mum. So I went with a plan. Late at night when everyone was sufficiently inebriated, I changed into some kind of cabaret-style costume (no doubt influenced by the film Cabaret). I remember it well. Tights with a greenish hue, shorts made from cut-off male dress pants, hair brushed to the side, make up and – of course – the infamous narrow moustache painted on. I jumped on a table, did the Heil Hitler gesture, gave some loud silly speech which I cannot remember, did some kind of personification of Charlie Chaplin’s dictator, and so on. Quite a show. Of course I expected it would be provocative. But I had no idea what would happen. The older generation, my grandparents, and my cousin’s grandparents, teared up. Suddenly everyone teared up. I just remember everybody crying and screaming at me. It turned into a literal angry “tear-bath.” I felt awful. Ashamed.

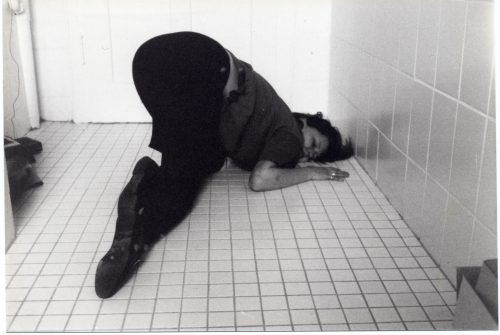

“SELF-PORTRAIT – QUITTING HOME” 1988 © Máire Noonan

Later, as I lay in bed, in the dark, my mother sat on the bedside, stroking me. We were both crying. She clearly abhorred what I had done. So why was she consoling me? This was an episode in my coming of being that I remained quite ashamed of. Until one day when, in Montréal, I was well into my forties, my younger cousin’s cousin from the other family branch, now a young and dashing artist, was visiting Montréal. We had an evening, a soirée, lots of people, including her. And suddenly she remembered and recounted this episode! She was 11 years my junior, so she would have been what, eight years of age? And apparently she carried away an everlasting impression of this. Wow! I had no idea. With all the hurt and tears I’d caused and my being shamed, I had not at all noticed any of the young kids who had witnessed all this uproar. I would never have guessed that it left a positive impression on anyone. But it did, on this one girl. In retrospect I feel, perhaps a little, pleased. But not really. It remains, largely, an ugly memory.

But … what was driving me in all this spite against Germans?

At this point I’ve lived in Québec for 30 or so years, with interruptions, and have thus gained quite some distance to Germany and my conflictual feelings about it. But guess what? Now I tend to collide with Québec’s dominant culture. Well, somewhat. I actually love Québec. I made Montréal the place to spend my life in quite consciously. I came here as a student at McGill, but I always sought the company of Francophones, of the Québécois. I was quite in love with Québec culture. Later I formally immigrated and lived here, as a professional, no longer a student. I married a Montréaler. I met all his Québécois friends. At first I was thrilled. Through him, I felt I had firmly cemented myself inside social Québécois circles. But little by little I started feeling – I’m not sure how to characterize it – like, sort of, in a way, well, I remained the outsider. There were those who saw me as l’Anglaise. I really resented this. I mean, I had grown up in Germany. English was, strictly speaking, my second language (albeit one that I acquired at a young age, being half Irish … yeah, the term l’Anglaise really rankled). I had learned to speak French fluently and made it my everyday language, with a lot of effort, as foreign languages don’t come easy to me. I was so motivated and dedicated: I read novels galore in French, looked up vocabulary to no end, turned myself into someone with an impressive vocabulary. I also learned Québecisms. I had started pronouncing tu as tsy and said things like c’tait le fun! But it wasn’t to be. I was not going to be one of them. Why did I want to be one? Or, did I? I certainly didn’t want them to decide I wasn’t one, estie!

An anecdote: after having lived on Waverly for over 10 years, I was out on the front balcony one early spring, gazing at the melting snow. Our neighbour was out too, and I mentioned how remarkable it was that our side of the street (the southwest-facing side) had no snow left, while the other side still had mounds of snow. She replied (in French): Yes, sometimes un nouveau regard was necessary to notice obvious things that could remain invisible to the habituated. WHAT?! Un nouveau regard?! Me?! I’d actually lived longer in the block than she had! WTF?! Estie d’tabarnac! Oh… yes… of course, I’m the outsider. Avec un regard frais! My ass!

When I tell such anecdotes to my Québécois friends, they dismiss them. When I tell them to anyone else – Anglophones, immigrants, any non de souche Québécois, they just smirk and look at me like, well, DUH!! (Why bother stating the obvious?)

Let me return to what I started with. The child, the urge to blend in. So why did I have this penchant, ever since I can remember, to rebel against “my immediate society,” perhaps best characterized as “the dominant culture?” As mentioned before, regarding Germany, I always thought it was my German guilt complex. I carried the Ur-Schuld of my grandparents. But recently, and amazingly late, it dawned on me that there were other elements. In fact, growing up in Germany, I was half Irish and had an Irish passport. I wasn’t permitted a German one until the law changed and I was twelve – “blood right.” My father was a foreigner. My name, and the perennial reactions to it: was für’n komischer Name! (“What a funny name!”). I was a little proud of it, but also somewhat annoyed (especially when they called me Möhre – German for “carrot”).

My father: when my mother was going to marry him, her parents were quite opposed to the marriage. First, he was Catholic (god forbid! Ha ha)! Then he was an Irishman. And she had cancer – Hodgkin’s disease – and they didn’t think he would make a “responsible” husband. My grandmother (“Oma”) forced my grandfather to write him a long letter, trying to discourage him. They married anyways. True love and so on. Well, of course Oma ended up being right (she usually was). He turned out not to fit the bill, and abandoned us (well – to be fair, my mother packed his suitcase and sent him back to Ireland after him having ranted at Germans and Germany for several years, and after having moped, jobless, on the sofa for a year – I was only eight, but I remember her coming home from work and clearing his breakfast dishes away while he was watching sports on TV).

Anyway, so I was not only half Irish with a funny name, but from age eight on, I was the child of a single mother. I also had cystic fibrosis. It wasn’t much foregrounded in my mind, luckily, no doubt thanks to my so wonderful, wise, and super strong mother. But I did have at times a persistent cough. And cough fits.

Another anecdote: me standing in the back of a bus, coming home from school, submitted to a violent cough fit that I was frantically trying to suppress (and – you know what happens when you try to suppress a cough fit!). Two girls, whispering about me. Loud enough for me to hear how people with a cough were just soooo unpleasant. Oh how horrible I felt! My self-shame smothered all the rage I should have felt against them. I should have kicked them out on the sidewalk at the next stop.

After primary school, my mother wanted to send me to a progressive high school, with a progressive Willy-Brandt-voting principal. But, because my best friend went there, I wanted go to a conservative high school, the one where the kids of doctors, lawyers, and other unpleasant conservative creatures went. My mother tried to refuse, but I was an insistent kid. So she sighed and reluctantly agreed to go to an interview with the principal of that other school who promptly made the mistake of telling her that this particular school wasn’t suitable for me: well – she was a single mother, a simple lecturer at university, not a professor, lawyer or doctor! My father – an Irish renegade Catholic, writer, I mean, c’mon! Well, he got that one wrong: She told him that she thought this was exactly the school that I was suited for. And so that’s the school I went to, to my bliss (and did very well at, thank you very much, you puffed up snob elitist piece of work of a principal!).

Anyway, yes, so there I was, half Irish, often sick, growing up with a single mother, who to top it up had serious health problems of her own. My father gone back to Ireland, a short story writer, and no provider by any traditional means. I thus realized, but much later that I, a white girl growing up in Germany, was indeed, and had always been, something of an outsider. An unwilling one, so unwilling that I was not aware of it. In denial. Good for me! As soon as I was old enough, I left. First to France, then to Ireland. Then to the U.S. on a fellowship from the German Academic Exchange Service, and finally to Montréal. I left Germany at age 22, and promised myself never to return to live there (except possibly to Berlin). Well, I kept that promise.

But here I am, now. My querulous self, now colliding with Québécois culture. I get into endless, exhausting and useless arguments about racism and ethic nationalism in Québec. I’ve given up on some of my more nationalist-minded friends. I feel growing affinity with “outsiders:” Muslim women wearing head scarves, targeted by laws and charters under the cover of laïcité (only thinly veiling its Islamophobic roots). Most of my friends, at this point, are exiles, people who came here from outside, who do not fit the bill of dominant culture. I live with a francophone Egyptian, who arrived when he was seven, who should be considered a Québécois, but usually is not. (As a kid, when other kids called him a sale Arabe in school, he denied that he was an Arab and went home to ask his father: Mais papa, on n’est pas des Arabes, n’est-ce pas? On est des Égyptiens! His father explained that they were nonetheless Arab: “Mais oui, mon fils, on est Arabe. Et pourquoi pas?” One of his teachers called him l’Égyptien – the others were called by their name – and it made his blood boil. He was friends with the only black boy in his school, a boy from Haiti). As an adult he has been making his living as a freelance artist. He does fine. But note: he mostly gets work from Anglophones or others from the immigrant community (well… he did commit a few venial sins: married an Anglaise, studied at McGill and voted “No” in the last referendum). And so it goes.

“Root” 2017 © Máire Noonan

So here is the thing – I’ve always felt more affinity with those who are outsiders, who are on the margins, who do not fit, somehow. And here is the beauty of it: I am happy with it all! At peace. I have been becoming increasingly attracted to those who are also on the outside, the “exiled.” Those who understand what it means to leave the comfort of your origins behind and absorb a new culture, a new language.

There is an infinite community of “others” in Montréal. This community includes some Québécois de souche, though I often wish there were more! But this is my gang. I have, finally, in my fifties, found my community. That which isn’t one. That which floats around, doesn’t fit, and yet fits. That which makes this city, this country, rich. And now, I’m declaring it, I’m shouting it out: I no longer want to belong to the “dominant culture.” After years, I finally acknowledge, and reject its hegemonic tendencies. The small-minded esprit of those who have a conception of Québec culture that excludes the other no longer interests me. Yes, it is official. I no longer want to belong. I’m happy on the margin. I will forever want to be on the margin. It has been a long time coming. As my love said the other day: this is our golden era. “Our” being those on the outside. It is our moment. If Montréal didn’t make us its own, we’ve been making Montréal ours. Yes.