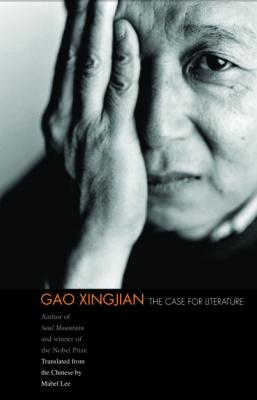

Gao Xingjian, playwright, novelist, essayist and painter born in eastern China and self-exiled in Paris, was named a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French government in 1992. In 2000 he went on to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature. In the words of Mabel Lee, his translator, The Case for Literature, the title of Gao’s Nobel lecture and of this present book of essays, is a demonstration of “the intellectual and aesthetic dimensions of the thinking that informs Gao’s creative writings.” It is also precisely what the author claims it is: a plea for the centrality of literature as the “universal observation on the dilemmas of human existence and nothing is taboo”. Gao explains that “restrictions on literature are always externally imposed, by politics, society, ethics and customs, which set out to tailor literature into decorations for their various agendas.”

Gao’s thesis is deceptively simple. The writer is neither a hero nor an idol. Conversely, he is certainly not a criminal nor an enemy of the people. Literature “has to do battle with the subversive commercial values of consumerist society”. He reminds us that writers like Kafka and Cao Xueqin were never published in their lifetimes, that they lived mostly on the margins and seams of society, expecting neither recompense nor social approval. He also warns us against thinking that writers are prophets. In fact, he stresses the importance for the writer to live in the present, to cast off delusions and to shed light on his own self.

What has all this to do with the loss of human rights, the subject of this Montreal Serai issue? A lot. By the mere fact of living in a highly collectivized society, call it communist China, Confucian China or just plain racist and nationalistic China, the author suggests that he lost his freedom of expression, a most basic right in any humanistic society. Gao believes that a writer can only speak for himself and never for a group. He never decries political participation by the writer, but warns his readers that the only “responsibility a writer has is to the language he writes in.” In fact, he laments the tendency of societies to expect writers to be spokespersons for the dominant ideology. He very strongly believes that a writer should “return to being an ordinary person, born in original sin and without special privileges or powers, because this is the most appropriate position from which to observe the human world.”

A word about truth. For Gao, the search for truth can never be exhausted, and that search can take place through fact or fiction or a mixture of both. What matters is that “literature is a refuge for the free spirit and the last bastion of human dignity”.

Since this is a collection of essays, the content of this book does not add up to a cohesive whole. In “The Modern Chinese Language and Literary Creation”, Gao explains the difficulties involved in translating a highly dialectical language like Chinese which is contextual and includes calligraphy in its aesthetic sensibility into European languages which are Cartesian and hence clearer, but more limited. “Another Kind of Theatre” is an outstanding exploration of the meaning of theatre. “Theatre is action”, Gao says succinctly.

Towards the end of the book, in “The Voice of the Individual”, the author finally touches the subject of Chinese intellectuals and individual rights. In his opinion, before the 1911 revolution, China’s intellectual class was peopled by scholars or gentry who were only concerned with Confucian morality. Daoist intellectuals were oriented towards nature, hence non-action and Buddhist intellectuals, by striving for Nirvana, further eroded individualism. Individualism, posits Gao, is “a recent product of the rationalist traditions of Western Protestant culture and the subsequent flourishing of capitalism”. In the past Chinese intellectuals found it hard “to separate learning and literary creation from politics” and contemporary intellectuals continue to do so. In China, “There is still no guarantee of basic human rights such as freedom of speech, publishing and news reporting”. Gao urges writers to just try to save themselves instead of trying to save monolithic China, which is what he did by hiding in the forest for six months. He is also talking about himself when he says “Chinese intellectuals have suffered extreme hardship”. However, he carefully differentiates between true individualism and “a tragic belief in the supremacy of the individual”. For Gao, basic human rights involve limited freedom, since “responsibility and cooperation, respect and tolerance are necessary preconditions for realizing the will of the individual and the expression of the self in modern societies”.

Gao’s lapidary conclusion is that “the existence of literature” – and of writers- “depends on the writer’s willingness to endure loneliness.”

For information on writers imprisoned or exiled, from China or elsewhere, please consult: http://www.pencanada.ca

Maya Khankhoje is a Montreal-based short story writer, poet, essayist and reviewer. Her English translation of Paulina y la Golondrina Azul, (Paulina Wonders) by Carmen Cordero, was published last November in Madrid, Spain.