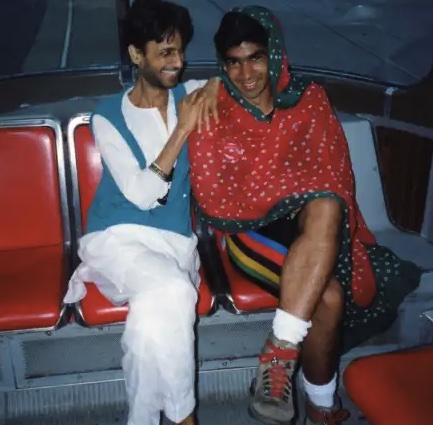

The connection was immediate and profound. After years of isolation, all of a sudden there was someone I could talk to about the things that I was going through at the time as a queer South Asian man. His defiance of heteronormative culture and his activism seeking justice for people living with HIV/AIDS were inspiring and gave me the confidence to start to express my queerness through my own artistic practice.

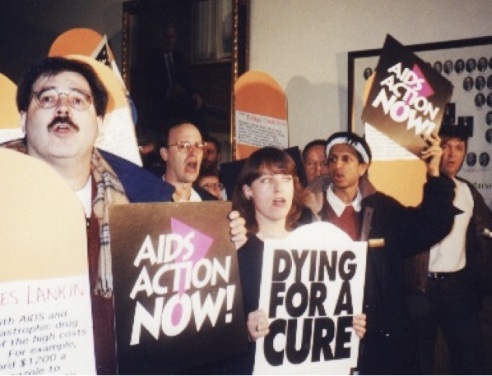

Kalpesh discovered he was HIV-positive in 1988. He continued his activism in spite of his failing health. and presented his last performance, “Living With AIDS on Roller Blades” at Desh Pardesh, the annual Toronto-based South Asian arts-culture-politics festival/conference that ran from 1988 to 2001. He passed away in Toronto at the home of his chosen family in June 1995.

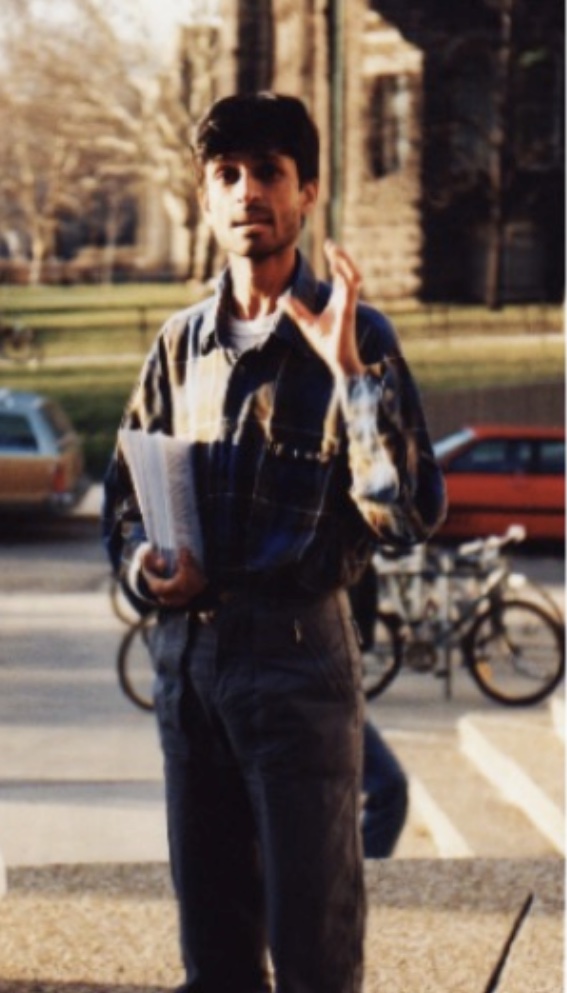

The following piece is my transcription of a talk given by Kalpesh for a panel on the theme of “Running from the Family.” The presentation took place at the Desh Pardesh conference/festival in 1993. The transcription was originally published in the Fall 1995 print version of Montréal Serai (Vol. 9 No. 3), before the magazine transitioned to its current online/digital format. Some editing was done for continuity, however, we have tried to maintain Kalpesh’s conversational style as far as possible.

—Himmat Singh Shinhat

Photo AIDS Activist History Project

MODERATOR

Kalpesh grew up in India and migrated to Canada when he was 24. Since then, he has been back to India three times, each with great news from his family. The first time he went back, Kalpesh came out as a gay man. The second time he went back, he came out as HIV positive. And the last time he went back, which was perhaps his most difficult trip, he finally brought his politics out of the closet.

KALPESH

I’d like to give a brief background of my parents’ families, or rather a background of my parents, because I think I want to make a point about how a lot of times liberals can turn into not only neo-conservatives but fascists, and I don’t throw around the word “fascist” just like that. Only when people start talking about… in an Indian context, when high-caste Hindus start talking about killing Muslims or sending them to Pakistan and Bangladesh, I think that is fascist, and it’s not just that I’m throwing that word around.

My parents were pretty progressive. My father used to be in a socialist party. Theirs was not an arranged marriage. They lived together in the 1950s for two months before they got married. One doesn’t do that sort of thing – even today, it’s very rare in India. My father was involved in the independence movement in India, and so on and so forth.

My mother, at the age of sixteen, moved to Bombay from a little village in what is now Gujarat and what was then a part of Bombay Province, and she made her life there and met my father. They met, they lived together, they got married. Today, my father is very strongly anti-Muslim. How did that come about? Like, was he really progressive, or merely a liberal who thought it was nice to tolerate everybody’s existence without actually understanding that everybody has a right to exist?

When I told my father first of all that I’m gay, his immediate reaction was very positive, expressing concern for my life. The first reaction was: “I hope you use condoms all the time.”

Also, that that would reflect on how they reacted when I came out as a gay man, which was, comparatively speaking, a very supportive reaction, and when I came out as an HIV-positive person, which was even more strongly supportive but slightly schizophrenic. I’m saying schizophrenic because on the one hand, I see that part of Indian culture traditionally encourages looking after sick people, irrespective of what (illness) or how the person became sick. On the other hand, they have all these moralistic attitudes that you see in today’s India, which is also reflective of the current, as I’m saying, at the international level – that there is a rise in right-wing movements or a rise in fascism.

So, when I told my father first of all that I’m gay, his immediate reaction was very positive, expressing concern for my life. The first reaction was: “I hope you use condoms all the time.” And this was in India as early as December ’86, a few days after my arrival in India. It was my first visit back home since I moved here in 1984. Three weeks later, the day before I was set to leave India, he came up to me and said that I was just making it up that I was gay – I just didn’t want to get married, I wanted to lead a promiscuous life with women, hence I was making up an excuse that I was gay.

So, within three weeks how did he change? I think that his gut reaction was very positive. He told me this story about how his father – my grandfather – told him that when two women don’t get married and go to live in a big city to maintain anonymity (…) and in his grandfather’s words, one plays the role of a man, the other of a woman, that means they are lovers. My grandfather had told this to my father because their neighbours, two women, had eloped, and somebody had brought back the story that they had eloped to Bombay, which gave my father the idea of going to Bombay and living there. So actually, it was my grandfather who planted this idea! A similar story goes on my mother’s side, too, that it was my mother’s grandmother who planted this idea; while criticizing somebody who had eloped to Bombay, (she) planted the idea in my mother’s mind to elope there.

The most difficult part for me was the last visit, which was in January 1993. I prefer calling it “bringing my politics out of the closet,” not because it was the first time I had told my father where I stand on certain issues or on any issue that we were discussing – ever since I was a kid we would discuss a lot of politics, a lot of issues, and we would land up in arguments – but because it was only this time that I realized it’s always been a “matter of opinion” up until now. In my family, everything was ultimately reduced to the level of “matter of opinion,” which means, no matter what opinion you have, you tolerate – blah blah.

This time when I seriously questioned, from a larger political perspective, how my father treats my mother, and in an equally inhuman way, how my mother treats an army of servants, and in an equally inhuman way, how one of our servants beats up his wife – which I did not really contest or debate with the servant, just briefly mentioned it to him because, once again, in our rapport, he works in my parents’ house so I didn’t want to get into that because of the power imbalance between the two of us, as it would be unfair if I kind of dictated what he should do – I took it upon myself as my right not only to argue but to fight with my parents, my mother and my father, about the way they deal with people in society.

It’s not ultimately the personal life they are questioning. They have very upper-class attitudes, and insofar as you support certain norms, certain structures of upper class, anything is fine. You can be gay; you can be HIV positive. That does not mean there is no discrimination: I don’t want to demean my own experiences and the torture that I have had to go through as a gay man, especially in the closet, wetting my pillows night after night with my tears, thinking that it was wrong, or not wrong, but that it wasn’t going to be accepted. Much more shame than guilt – when I think about discussing with Punam, a year or two ago, the difference between guilt and shame, because I had heard these white people talking about guilt and I had not understood – now, after the last visit, I understand.

After the last visit, I understood very clearly the image (of me) when I was 13, going to school, and I thought, “Well, I’m gay, that’s not bad; like, at least I don’t cause harm to anybody.” There was no guilt, that was clear. What was there was shame and fear. What am I going to do when I grow old? I’m going to be alone, and in a society like India, or here, too, where much more importance is put on nuclear family, (whereas) in India, joint family. But I think ultimately, (…) to a certain extent there is this same kind of fear for lesbians and gay men, of loneliness, especially in the absence of the lesbian and gay movement.

So, once I finished my degree, I decided to run away from my family. In retrospect I think that was one of the main reasons for running away from my family. Otherwise, I would have probably become a lawyer as my father had insisted, and we had a lot of fights about that… I would have lived in the same city, lived with my parents.

One thing I had told my father when I was 13 – which is a very lucky number for me by the way, because before 13, I was a little child ready to cry with a pout on my face, sitting in a dark corner. That’s the image, that’s the description I give of myself before the age of 13, and after that I became a rebel! It was at that age that I told my father, being very sure, that I wanted to study genetics. I think it was really great that I ended up studying genetics. Even now, I am employed as an immunologist, but they have employed me as a geneticist to study the genetics of the immune system. At the age of 13, I told my father I didn’t want to get married and he just laughed it away. I’m not married – well, it depends on the definition of marriage, of course, but I have to stick to the definition I had then, and according to that definition, I’m not married.

So, running away from the family. Having grown up, spent my childhood and adolescence in this particular family, when I ran away from my family I went to Baroda, Bangalore, then came to Canada, lived in Windsor for a year, in Montreal for six years, and it’s been almost two years in Toronto. I came out as a gay man here in the west, obviously in a city like Montreal, which to date has not a single group of lesbians and gays of colour, either lesbians of colour or gay men of colour. There’s not a single group. I went to a predominantly white group, GALM, Gays and Lesbians of McGill, and my very first time there, people were discussing a person that I had never heard of. I very innocently asked “So who is this person?” and this guy goes, “You haven’t heard of Judy Garland and you call yourself gay?” That delayed my coming out by about a year and a half… It did!

It did, because I was very nervous to go to this organization for the first time, to begin with. It was very painful, this kind of reaction. I was just so nervous, so depressed, that I just didn’t have the courage to go back into an environment that I felt was much more (…) alienating than my family, because at least I had grown up with and had some sort of links with my family. At that point I knew, anyways, that I could fall back on those links from my childhood and adolescence, although I wouldn’t put it the same way in today’s context. So, my coming out was delayed, and I most certainly did not consider lesbians and gays my family, either. It was really kind of a difficult period at that time to come out.

The last point I want to mention is that a lot of times, what (we have is) – at least in my experience, and for a lot of gay men friends of mine of South Asian origin, as well as for lesbians-of-colour communities and other people-of-colour communities that I have talked to – when we come out, some of us also kind of shun our families because of our personal experiences… And our internalized racism manifests itself in certain comments that we make, like the notion that people with darker skins are more homophobic than whites. At least, coming out as a gay man, my experience has been, comparatively speaking, much more positive than most of my white friends’ experiences of coming out. And friends, too, in India, a huge number of friends, once again, I always stress, comparatively speaking.

My brother is a very active member of the BJP, which is the anti-Muslim, fascist party in India, with very front-line persons. We have had enormous fights, and he says that it’s really stupid about gay rights, it’s really stupid that the government has decriminalized homosexuality. I had to point out that it’s not the government. Homosexuality most certainly was not accepted but it was tolerated (on the lower scale of tolerance) before it was criminalized during the Victorian era. It was a British-imposed law. In describing this, in telling him this, I had to constantly be aware that I didn’t want to fall back into nationalism – “oh Indians were better, there was less homophobia, etc.” – because that would be an insult to my own experience.

It was kind of like falling into nationalism while trying to tell white lesbians and gay men “it’s not as you think it is.” At the same time, falling into the nationalist trap hurts my own rights as a person of colour, as a gay man, as an HIV-positive person here and in India. So, running from the family, I thought, would be the solution – but it hasn’t necessarily been. And going back to the family, as I have already said, is most certainly not the solution either. So, I’m still looking for solutions, essentially.

Thanks.

Kalpesh Oza

(1993 presentation at the Desh Pardesh conference/festival in Toronto)

Left to Right: Gary Kinsman, Brent Southin, Maggie Atkinson, Kalpesh Oza, Glen Brown – Photo AIDS Activist History Project

For photos and tributes: AIDS Activist History Project, the AGQ (archives gaies du Québec), and Kalpesh’s obituary in South Asian American Digital Archives (SAADA)