To start out, I have taken great pains to not consult academic or internet classifications of the subject that I have chosen to write on, and have allowed my mind to wander and evolve. As a result, there may be some definitions that are totally out of sync with the understanding of specialists on the subject. I could say one thing, though! I have understood what the Adivasis (the original inhabitants of India, in Indian languages) and the Indigenous peoples in Canada aspire to when they talk about Nationhood. It pertains to their relationship with the mountains, rivers, forests and skies with which they have desperately attempted to maintain an equilibrium. And non-Indigenous, be they settlers, colonialists, predatory capitalists, miners, golf players or housing developers, have made sheer hell out of those attempts to restore balance. This notion of the nation has evolved, and boundaries seem to have become an irrefutable requirement for defending the rights of the people who want to live peacefully and at ease with the environment.

I will begin with a bit of history that I am very familiar with, due to the research I undertook during the pandemic as I embarked on my fourth novel, Shaf and the Remington.

Nations have borders and boundaries

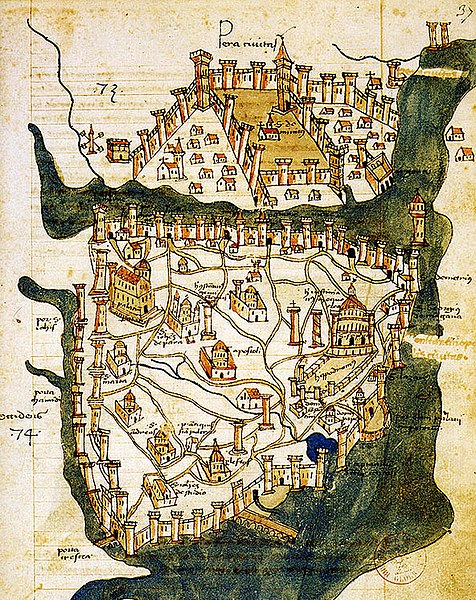

On the 29th of May 1453, a 21-year-old Sultan named Mehmed II led the final assault on the Byzantine Empire, and Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Empire after nearly 1500 years of Christian rule. There is much written and posted on the internet on this issue that is spectacular, obscene, ugly and sometimes salacious—and often made into side stories and films.

There are details of each military campaign, including the metallurgy of the largest cannons made at that time! There is also a description of the amount of lard that was spread surreptitiously by the Sultan on logs laid out on a deforested roadway across Galata on the north side of the Golden Horn, so that his ships could be dragged over the land and bypass the chain barrier that had been set up to prevent an invasion by the sea. What was pivotal was that physical control of this important city (and therefore of the Bosporus) was crucial for both the Byzantine Empire (Christian) and the Ottoman Empire (Muslim).

Control of the physical boundaries of nations was considered fundamental to rulers, whether they lived in palaces or forts and demonstrated their opulence by building plazas, mausoleums and museums, or carried out rapacious military campaigns. They trundled off their populations into churches, temples, synagogues or mosques for spiritual reinforcement or divine intoxication. It was considered the end of the medieval period. Fortifications, borders, obstacles (whether natural or constructed), strategic access roads to warm-water ports, and access to trading routes, canals and river routes were central to the definitions of national boundaries.

The concept of nation was not an imaginary or utopian notion of togetherness for ethnicity, religion or language. Nor was it the more pernicious “definition” of a nation as a global agglomeration of followers of a single religion, which has been perpetuated by Zionism and imitated by some other religions.

Preservation of a nation meant that invasions had to be prevented by defined natural boundaries (mountains, seaways, rivers and dense forestry) and by constructing thick walls around cities, fortifying seaways with cast iron chains, and deploying military engineers from Hungary, miners from Serbia, and mercenaries of Genovese, Vatican and Venetian origins. Needless to say, there were no hypersonic missile systems then, no iron domes and no cyberwarfare. Everything was done on land and sea to prevent infantry and naval invasions.

The point of this segment of the essay is to emphasize that the physical territories of a Nation define its political and economic space. A nation is defined by its geophysical borders, often reluctantly agreed upon in the modern context, despite some lurid political and historical details about the acquisition of land by force, by treacherous deals, and sometimes by sheer occupation… like Texas, California, Louisiana, Alaska, or for that matter, New York. And even today, control of the Black Sea and the port city of Odessa becomes crucial for both Ukrainian and Russian forces, not only to receive armaments, but also to ship grain.

At the next level, we have the nation state.

The nation state is how the nation is run. By governments (via election or coup d’état), based on constitutional provisions, generally. (Almost all nations in the world have constitutions, except the UK, Israel, Canada, Saudi Arabia and New Zealand, which do not have a single document codified as a constitution). The methodology of running the state—whether by local councils, by popular democracy (borough committee, flawed or otherwise), or by regimented or militarized means—shapes the state apparatus that defines the day-to-day rule over the people of a country. The state could end up policing the people, taxing the people, codifying laws about the way people must live their lives, dictating what they can wear and what they can learn, and then demonstrating largesse by providing relief and dole.

You will notice that by now we have started talking about people. That is when we suddenly realize that what seemed like a delicate and sophisticated exercise in understanding or getting excited about the running of the state, the constitutional laws that govern it, the regulations and legal systems that are supposed to provide fairness and justice to its citizens—is not really conducive to the rights of citizens. The state is paramount and its preservation and perpetuation are far more important than the rights of 99% of its citizens. That moment of realization is a crucial point in time, where citizens and their representative organizations must either cooperate and sublimely submit to the processes in the larger interests of the state… or consider an insurrectionary process, perhaps?

The nation state has governments, elected through a process, be it parliamentary or non-parliamentary, often self-defined as democratic (even when carried out under a military commission or foreign intervention), but with a variety of constitutional and electoral safeguards, judicial systems and policing systems that justify the control of the state by the government. There is often more than one level of parliament, and it is said that most modern states have chosen to separate the executive from any religious control. Elections based on first-past-the-post or proportional representation are the contending notions of majority.

In a liberal democracy, the people get the government they want. As elections approach, divisive issues are raised, instigating dormant fears within the population, and real issues of economic and political rights get sidelined. As an example, here in Québec, the issue of Québec values (the so-called Charte des valeurs québécoises) was introduced in 2013 (under Bill 60) and as usual, a silent majority of people smiled and nodded with extraordinary politeness as they went to the polls to vote for a non-inclusive and even non-democratic society, all under the name of laïcité.

The Parti Québécois, which spearheaded the push for “Québec values” and an insular brand of secularism, lost its shirt in the elections. Its successor, the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ), introduced and passed the laicity bill (Bill 21) and has continued to promote the same value systems in various pieces of legislation.

Nationhood, however, is not about borders, bills, physical contours, customs clearance or toll gates. It is a state of ancestral learning and continuity—lessons learnt in relationship to the land, the mountains, the forests, the sky and the people who have lived under it. It is about the historical and intellectual continuity of those who were there from before. The Indigenous peoples, the original inhabitants of the land—their struggles, their opposition to colonization, their efforts to preserve their languages and culture.

Nationhood is not about countries, maps and elections—but about a relationship of any given peoples with their environment. Land alienation has become the principal way of encroaching on nationhood. It is achieved by encroachment on mineral-rich areas, displacement of local inhabitants, deforestation, and imposition of a system of economic welfare through neo-liberal economic warfare against Indigenous populations. This is happening in Latin America, in Africa, in India, in Australia and in various other parts of the world. Canadian mining companies are at the forefront of such activities, pivotal in undermining nationhood, especially in Latin America and Africa.

Almost everything we have touted as “Western civilization” is now no longer tenable… because it has been a mendacious assault on extracting value from the earth, and then more. The evidence for that is bloody—from Indian residential schools and the Sixties Scoop to the climate disaster. We have been comfortable with our sense of civilization and feel uneasy when it is challenged at the fundamental level. Science, education, knowledge and research have not led to reduced poverty levels or common prosperity… far from it.

Europe foisted on the world the notion that the “right to colonize” was a natural outcome of the superiority of civilization. By that logic, to civilize the “savagery” in the rest of the world was a natural evolution of deductive reasoning that Europe’s industrial revolution required, from the 15th century onwards. This sensibility is in itself a savagery, and colonization or decolonization is a topic in itself. However, nationhood remains a concept that needs to be embraced and understood as independent of the structures of nations, nation states and people.

There is a fable that Mahatma Gandhi was asked by a reporter what he thought about Western civilization, and his reply was, “It would be a good idea!” Irrespective of the veracity of the event, that sounds like something Gandhi would be quite capable of saying.