Memoirs are often described, in review and by enthralled readers, as “charming.” Robyn Sarah’s newly published Music, Late and Soon is not such a work. Deeply interdisciplinary and challenging, it bears intimate witness as the internationally acclaimed Montréal poet reckons with the parallel strands of music and writing interwoven through her creative and inner lives. When a memoir opens with a preadolescent girl riding a crosstown bus to a piano lesson after school in 1960, and closes with her at 65 on the same bus, visiting that very same, aged teacher in hospital, we the readers are more in the territory of the uncanny than in the realm of light memoir.

The book details the author’s re-entry into the world of classical piano, a world she left behind in young adulthood to instead pursue writing. In so doing, it brings to life many of the people who were meaningful to her over the decades, and their contributions, all the while musing on the nature of creativity and work themselves.

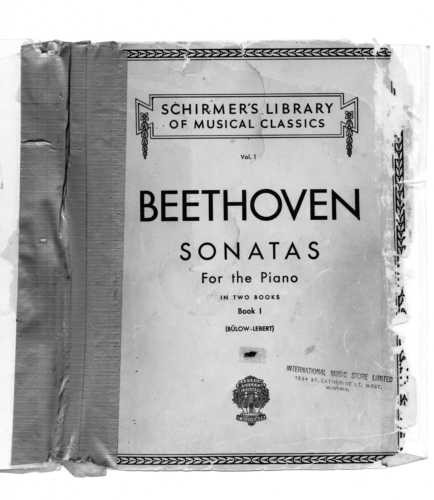

Within the memoir, the theme of time—in terms of life forming into a sort of groove that deepens and reworks within a certain geographical space—is constant. Indeed, as Sarah returns over and over to the grooves of her own Montréal life, the book brings the reader repeatedly to the place of the uncanny, offering a mixture of the poignant and the surreal. Sheet music taken out of boxes and pieces picked up precisely where they were left 35 years before is one of the eeriness-of-time moments that recur throughout the memoir. What is time at all, in the sense of each of us in constant flux yet always remaining that same us, in constant, lifelong dialogue with ourselves?

Sarah also delves into life in its tendency towards connection, loss, or reconnection with those who become special to us from childhood to old age. What of the mysterious roles that others will play for us in the short, medium, or long term? How is it that one beloved person may fade from our life, and another may disappear only to re-emerge after years, while still another may remain a constant through the decades? And most importantly to this particular and sensitive text: how can writing, music, and their creative overlaps define and characterize a life?

Through twin strands of the musical and the literary, Sarah explores the concept of vocation. A singular project in terms of a book of poetry or preparation for a recital may be “finished,” while still always operating within the always unfinished space of a life in art. Writers can and often must work on deadline; study of an instrument cannot be completed in any such manner. As Sarah’s beloved and enigmatic piano teacher Phil Cohen—a central figure in the memoir from the author’s childhood to adulthood—explains, music is never finished. A piece can always be reworked and explored for more and different elements, an instrument can always be played differently, with new sounds evolving new techniques. For the pianists under Cohen’s mentorship, musical training means a life always unfolding in and with music. Where Sarah feels sheepish and childlike to return to “piano lessons” in her later fifties with grown children, Cohen is utterly unfazed; instruction has no age, lessons have no end date. Music and its pursuit simply end only when life does.

Cohen is sketched in the memoir as an iconoclast and a sort of mystical bohemian in early references to him in the book, around 1960. Influenced by physiology, neuropsychology, Eastern philosophy, and mysticism, he brought his unique philosophy on the inherent interdisciplinarity of music and science to both McGill and Concordia Universities. Cohen was a cofounder of the Leonardo Project at Concordia, a highly innovative initiative formed in 1992 to explore the interdisciplinary interplays of music and science, indeed of science in music. Sarah describes Cohen as a teacher who offered his students “a musical Kabbalah… a guide for how to live well in the world.” In such a musical/existential worldview, “there are no answers and there’s no right way.”

The reunion of Sarah and Cohen as pupil and teacher at the age of 59 and 80, respectively, forms the heart of the memoir. Their relationship is particularly representative of the ways in which time is often presented within the memoir as something weirdly ineffectual, unable to break decades-lost connections or change the essential core of a person. Perhaps Sarah’s book is longer than typical for a memoir because of a guiding philosophy that emerges in the later pages, applied to both music as vocation and to writing: “It’s not about finishing something. It’s about keeping it alive.” We come to understand this quote as applicable to a life’s work, a musical practice, a memoir 10 years and many decades in the making, or a beloved lost-and-then-found creative collaboration and friendship.

The book is circular as a text, much the way that ideas of time, past, present and future are explored in the author’s life throughout it—in flashback, blurred timelines, and stressed continuities. The middle section, with its musical title Entr’acte, is a meta-discussion of the writing of the book itself and its metamorphoses, circa 2017. Indeed, the memoir’s circularity serves as a stylish effect, in keeping with the idea of music as a kind of homecoming. Sarah mixes journals from 2009 with 1960s journals she found, detailing her life at the Conservatoire as a teenager—another strong choice in reinforcing the blurring of present and past as the work’s primary motif. She also skillfully weaves together the cultural and political fabric of life in Montréal and North America over seven decades, from her childhood recollection of the Kennedy assassination to her bohemian student days in the McGill Ghetto around the time of the October Crisis.

The author writes with a quiet strength and surety to her words—a trait somehow perfectly in keeping with the determined personality required for a lifelong dedication to high level piano. The memoir remains conceptually interesting throughout, even beyond themes and style; it is also quite cleverly organized into sections of musical motifs. Musical metaphors in writing, and writerly metaphors in music abound. Performance is explored as a type of acting, teaching as another. Highly imaginative and sensory sections on how it feels, smells and tastes to play a particular instrument are especially vividly drawn. A taste for interdisciplinarity and a working knowledge of musical terminology and concepts will be helpful for the reader. Music, Late and Soon is a book that will be most enjoyed by musicians and lovers of music, and appreciated by anyone who recognizes literary effort at the level of the magnum opus.

Robyn Sarah reading from her book, with Serai editor Jody Freeman

Note: Music, Late and Soon is shortlisted for the Mavis Gallant Prize for Non-fiction, issued by the Quebec Writers’ Federation.

More on Robyn Sarah

Poet, writer, literary editor and musician, Robyn Sarah is the author of 10 poetry collections, two of which have appeared in French translation. My Shoes Are Killing Me won the 2015 Governor General’s Award and the Canadian Jewish Literary Award for poetry. In 2017, a retrospective of her work, Wherever We Mean to Be: Selected Poems, 1975-2015, was published by Biblioasis. Sarah is also the author of two collections of short stories and a book of essays on poetry. From 2010 to 2020 she served as poetry editor for Cormorant Books.