[Editorial note: Studying classical Indian music is an immersive experience. It is part of an ancient Indian apprenticeship tradition known as Gurukula, living and learning music in the guru’s home. Students, or shishyas, move in with their teachers for a number of years as part of a spiritual journey that goes beyond melody and rhythm. This is what Aditya Verma embarked upon at the age of 18, when he left Montréal to join virtuoso sitar player Ravi Shankar in his home in Delhi. Here are some of his memories.]

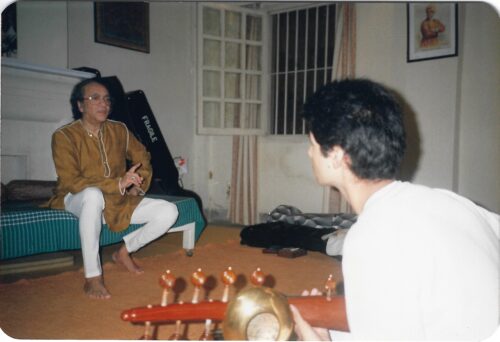

In August 1987, I entered the gates of Pandit Ravi Shankar’s home at 95 Lodi Estate in Delhi to begin my life as his shishya (disciple). It was a hot day and my palms were sweaty. I was excited but nervous at the prospect of a future living in a Gurukula, an ancient system of apprenticeship built on the sacred relationship between mentor and disciple, with this musical legend. As I approached the house, “Guruji” looked up and beamed a huge smile at me from his rattan chair on the veranda where he was drinking chai with the great singer Lakshmi Shankar. They were listening to a song in Raga Nat Bhairava that will forever be etched into my memory, “Uchata Gayee Mori Nindiya.” In the coming days, my nervousness would dissolve and give place to euphoria as I played my first notes on the sarod.

Earlier that year, I had visited Pandit Ravi Shankar in New York City, where he was recovering from heart surgery. My father, Dr. Narendra Verma, had been close to Guruji since his childhood, so I called him “Nanaji” (grandfather). I had gone there to give him support, but also to discuss the possibility of learning music. I grew up in Montréal learning to play tabla from my father, who is one of the most senior disciples of tabla legend Ustad Alla Rakha. Guruji tested my talents in music, rhythm and melody. Perhaps much more, though, he wanted to gauge my dedication to music and my willingness to surrender to the intensity of the traditional way, Guru-Shishya-Parampara, that is, Teacher-Disciple-Tradition.

It was the rarest of privileges.

A house devoted to music

Every morning, the gardener would bring flowers for the prayers. Someone would light the incense, and sounds began: the tanpura, sitar, sarod, tabla, with a different person practicing in every room. In spite of being in Delhi, a metropolis notorious for its capacity to overload the senses, inside the gates, the whole environment was conducive to learning. It was in fact a lot like a retreat, an ashram. The only thing that was really demanded of us was the purity of our intentions toward learning music.

The days were filled with lessons and practicing – often 10 to12 hours a day! There were four other shishyas living in the house with whom I often learnt and practiced. In doing so, we also became best friends. Guruji humorously called us his Panch Pandavas, a reference to the five brothers featured in the epic story of the Mahabharata. Many musicians visited the house, as well as senior students who came to learn throughout the day.

There was also what we call seva (or service): doing something for somebody, even the smallest gestures, like bringing Guruji some tea first thing in the morning, accompanying him during daily activities or attending events such as concerts. I would very often go with him on his walks. It was a wonderful time for me to listen to him speak about his own upbringing. As a young man, he was traveling and performing with his elder brother when he decided to step away from all that in order to live and learn with his Baba – a great sacrifice that was also the greatest blessing, the decision that allowed him to become the artist he was.

The gift of teaching

Indian music is an oral (not written) tradition passed on from Guru to shishya, which has been in existence for many generations. This is one of the reasons why a sitar player (like my Guru, and his guru before him) can teach other instruments such as sarod, bansuri, violin or guitar. Beyond the technique and proficiency of playing an instrument, the guru would transmit knowledge of ragas, talas, and forms and styles of playing.

I’ve played the tabla since I was a little boy, but learning to play the sarod, this beautiful North Indian melodic string instrument carved from a single piece of teakwood, implied a completely new vocabulary – a vocabulary I learnt through vocalization and song.

Initially, Guruji sang and I followed, often first singing the notes in Indian solfege, Sa Re Ga Ma Pa Dha Ni Sa, then reciting the right-hand strokes or bols: Da Ra Diri…, then finally singing the composition set to a rhythmic cycle of hand-clapping. Once vocalized, I then played it on my instrument. Guruji was a fountainhead of knowledge. Sometimes even just a small comment from him would lead to a new technique which would take weeks to master.

On a personal level, I underwent a difficult transition from my life in Canada. I initially found the adjustment overwhelming, and I felt homesick. Guruji sensed this in me and tried to lift my spirits: “If you can’t talk to me, who can you talk to?” My relationship with him progressively shifted from grandfather to Guru. And his teachings went far beyond music.

Traveling with him, accompanying him to concerts, I had the opportunity to observe his interactions with other senior artists, both on and off stage. I witnessed the kind of respect he showed other people, and how he expressed that respect. Guruji taught me life lessons that shaped who I have become, for which I am forever grateful.

Teachers such as Guruji carry compositions that originated hundreds or even thousands of years ago. Following a lineage that’s been passed down through many generations is a huge responsibility for both the teacher and the student, who are entrusted with the future. When you have had the good fortune of learning from a veritable wellspring of knowledge, you have a responsibility to continue that tradition and to pass it on to your students, propagating the culture to other people. It is a responsibility I take seriously. My teachers passed their knowledge to me with such effort and dedication and sincerity that it is my duty to do the same.

With the pandemic, I started meeting with my students by Zoom or Facetime, or in my backyard in Montréal, where I teach music in the same way that I was taught. A student will come and I’ll sing, and I’ll get them to sing the same passage back to me, and then they’ll play it back on their instrument to me.

Developing one’s own sound

The sarod is not an easy instrument. There are no frets or divisions between the notes, and you must balance pressure between your fingertip and nails to create a sound. It takes years just to develop a proper tone.

Aside from that, starting an instrument when older, as I did with the sarod, is very different from doing so as a child. I feel that with age you have the mental capacity to understand and analyze more with every new lesson. This can be a boon but also an extreme challenge, especially when you just need to practice repetitively to train your fingers and hands to respond. I learnt to embrace discipline as a joy, not as drudgery. Every moment became an opportunity to learn something. Though Guruji was very strict and traditional, he taught in ways that were engaging, stimulating and playful, and I found myself gravitating towards a mindset of always practicing, thinking about and contemplating music.

There was an immense amount of material. I tried to notate wherever possible, as music was rarely recorded. The rest was spent trying to absorb everything I could and developing critical thinking in music by listening to other students, recordings and performances.

In the early years, my practice was focused on just a few ragas, the scientific, precise, subtle and aesthetic melodic forms upon which the artist improvises his performance. Every raga is characterized by its own particular rasa, or principal mood (romantic/erotic; humour; pathos; anger; heroism; fear; disgust; amazement; and peace), and is connected to a particular time of day or season of the year.[i] The fact that the notes, moods and techniques were distinct from one another kept practice fresh and challenging.

Over time, every successive generation of musicians injects itself into the music, whether it’s in terms of intonation, interpretation or expression. Sometimes you may realize a detail that puts the composition under a different light, or you may improve on it based on your own experience… and you are able to bring your own feelings into the tradition. Purpose and intent are key.

The more I learned, the more I realized that there was so much more to learn. Knowledge is like an ocean, and I felt I had only fathomed but a few drops.

Aditya Verma on sarod, in a Montréal church in 2009

Improvisation and inspiration

In a recital of classical Indian music, as much as 90% of the music may be improvised, depending on the artistic facility and creativity of the performer. This creative latitude allows the artist to take into consideration the setting, his or her own mood, and the feeling the artist discerns in the audience before beginning to play.

For instance, while performing a concert, a musician may hear a small sound of appreciation from somebody in the audience at exactly the right moment, recognizing certain elements of finesse which are not necessarily evident. It makes you feel like you are connecting, and it puts you in an inspired state of mind.

At times you become like a channel: the music is going through you and you are not even fully aware of what exactly you are playing, you are so caught up in the moment. Those are very magical moments you hope will happen as much as possible – instants I owe to my father and gurus, and to the lineage of teachers who have preceded them for centuries.

For more on Aditya Verma’s music, please visit his website and Facebook page. You can also consult a variety of videos and a montage in tribute to Ravi Shankar.

[i] Raga Bhairav is traditionally performed in the morning, Raga Sarang and its variations in the afternoon, and Raga Yaman in the evening.