[Mara Grey explains the origin of her interview, carried in this issue of Serai, with Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) the world-famous Argentinian writer of fiction, poetry, essays and translations. In Grey’s words: “I returned to Buenos Aires in 1980, after 23 years of absence. And I was lucky enough to have a long conversation with Borges in that city. Then I returned to Montreal and became absorbed with my family and teaching duties. The transcript of the 1980 interview sat in my desk among a collection of papers. Patrick Barnard, one of the editors of Serai, knew of this interview and urged me repeatedly to publish it, because of Borges’ importance to world literature and because even people who dislike many of his views still recognize his importance. So, in 2014 I put my copyright on the material and submitted the interview to Montreal Serai where I am very happy it is finally being published.”]

©Mara Grey 2014

I first met Borges in the 1960s when he gave a lecture at Concordia University. I was a young teacher very much impressed by his stories which I had been teaching. Twenty years later on a return visit to Buenos Aires, where I grew up, I met him again.

It was a sultry morning in Buenos Aires as I walked up the hill from Retiro station across Plaza San Martin to meet Jorge Luis Borges, one of the master writers of the century, in his downtown apartment on the fourth floor of an antiquated building. Questions ricocheted back and forth in my mind about him, his controversial public image gleaned from magazines, T.V. images of people’s views– often negative– his stories, and his country. I wish I could’ve seized on the one crucial question to ask him. In the marble lobby I caught my steamy image staring back at me in the large wall mirror, and I pondered about the other mirrors, “the impenetrable crystals” in Borges’ stories and poems that “prolong this hollow, unstable world. In their dizzying spider’s web…”. Outside, through the iron-barred glass doors, the street shimmered in light and heat. A taxi stopped. In a swirl of colour and South American chic a young woman stepped out, paused a moment, then disappeared into a shop. Her self-assured swagger and yellow hair, stylishly pulled back, suddenly struck a resemblance to another, the notorious and spectacular Eva Peron dazzling the multitudes 25 years ago. Even in the 1980s and 1990s, this long gone madonna of the poor, like the gaucho, the tango and the Pampas, sill stirred the North American popular fancy for the Latin spirit in such show biz productions as Evita.

In contemporary Buenos Aires the Peronist effigies had been taken away, but the remnants of the past epochs linger on and shape Argentine life, not only in the epic scope that history and imagination give them, but in the more mundane events: in the drama of conversation, the winks, nods, hand gestures that accompany words and seem like secret signals belonging to some ancestral code; in the slow rhythms of time like the hot hours of the siesta when the city catches her breath and the streets empty, and the incense-like scrolls of smoke rise from the roasting “asado,” and the wines of Mendoza are uncorked in the daily rite of the family and food; in the shadows cast by figures sitting in a doorway, fan in hand, sipping mate; in the hot nights when snails ooze out from the blooming gardens searching for cool spots in the patios, and people stroll in the barrio, lulled by the strains of some tango, or “carnavalito”; or in those sudden encounters, rounding a corner, with gypsy women sitting in a circle on the grass in a park, shadowed by the large Rodin sculptures in Plaza San Martin.

Borges seemed in himself to be a measure of time, of Argentina’s history and myths. He had marked the turn of the century by his birth and bridged over the span of other periods and places in his stories as well as through his ancestry. He equated his military forebears with his yearning for an epic destiny, which he believed “the gods denied him, wisely no doubt.”

Borges’ literary life began early, He was born into a library, in a manner of speaking. His father was a literary man, reputed for his translations of such classics as Edward Fitzgerald’s version of Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat, and many of the English Romantic poets whose verses Borges first heard from his father, as a young boy. Being a rather frail and near-sighted child, Borges spent much of his time among books. He grew up with such masters as Stevenson, Poe, Mark Twain, Kipling, Henry James, Dickens, Lewis Carroll, Cervantes, and so many more from whose pages he fondly quotes long passages, Eventually, he inherited the vast library of his father. In fact, he considered this library, now much diminished, as one of the chief experiences of his life: “I sometimes think I have never strayed outside that library.”

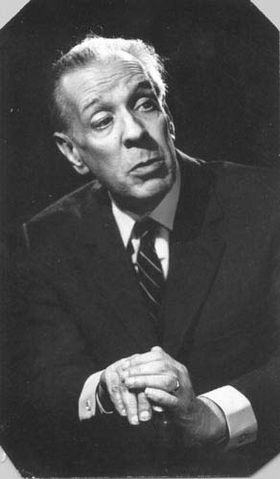

The following is a transcript of an interview of my two visits to his apartment at the heart of the city’s centre. He was then 80 years old, physically frail, but a giant of the mind so much so that his eyes, blind since the 1950s, seemed to focus and gleam intensely blue when he talked, particularly about books. I was using a small tape recorder which had an annoying ongoing cliquety sound like an old train on rusty wheels. And throughout our conversation, that sound and the telephone, the housekeepers’ voice, the clang and blare of traffic, and especially the sounds of Borges eating cereal –snap, crackle and pop– punctuated our exchange. I told Borges I was not a journalist but a teacher and a person interested in his work and life. Our conversations meandered from this to that, and often Borges’ words were cut off in mid-point by outside interruptions or his own thought processes which resulted in moments of silence. And I seem to remember thinking that what he did not reveal of his rich inner life ran parallel to his outer persona in that uncanny Borgesian identity split so poignantly illustrated in his stories, particularly in “Borges and I.”

M. G. Why do you write?

B. Well, (pause) I can’t do otherwise.

M. G. Is it an existential necessity?

B. No, I’m not sure what the word means. I mean if I don’t write I feel worried. I feel a kind of remorse, but that doesn’t mean I approve of my writing. It means I can’t do otherwise. It’s an inner need. I only write when I’m driven to it. I’m very lazy.

M. G. Have you written lately?

B. I keep on writing…

M. G. Do you have a discipline that you follow?

B. No, no. I have a few friends. So when they come here they are exposed to dictation.

M. G.You don’t use a dictating machine?

B. No, no. I hate the sound of my voice. I find it so vulgar.

[crunch crunch the sound of Borges munching Kellogg’s cornflakes, a legacy from his teaching stay in Austin, Texas, he says]

M. G. What is important for you; about your historical situation, living here. Why do you live in Buenos Aires?

B. I’m a poor man. I can’t afford to live elsewhere. I would love to live in Europe, America. Geneva. I love London, Venice. I’m not too fond of Paris. I think I’d love to live in Rouen, Bordeaux…

[Phone rings: voice of housekeeper]

M. G. How many languages do you speak?

B. One (laughs)… My French is very shaky. I thoroughly enjoy German.

M. G. You are perfectly at home with English and Castellano (Spanish)

Why do you write mostly in Spanish?

B. Out of respect. I love the English language too much. I don’t think I could…I have attempted English but…

[Telephone …Ring, Ring…Housekeeper’s Voice: “quien es? “Munch, munch…]

M- G. Can I ask you a question in Spanish?

B. Why not. We’ll have a shift.

M. G. Cuando vine aqui encontre que la gente habla de usted como escritor y hombre como si fueses dos cosas, o dos personajes separados. Usted piensa así también?

[People here speak of you as a writer and as a man, as if they were two different things, two different people. Do you think like this as well?]

B. No

M.G. Como lo explica entonces?

[How do you explain it, then?]

B. Bueno, I was not long to discover Coleridge, De Quincey, Milton,

that my life was to be a literary one. That reading and writing were all important to me. Later I discovered travelling. I spent 5 wonderful weeks in Japan. I was invited by the Japanese Foundation. We travelled to many cities, many temples, gardens. I talked with Buddhist monks and nuns. That was a year ago. Then I went to Egypt also. There are two countries I like to know. India, of course I know Kipling by heart…Indian philosophy… I would like to know China also. When you are in Japan, you feel China. China is to Japan, I mean, what Rome and Greece and Israel are to us.

[“Hola quien es?” — “Hello, who is it?”]

M. G. Are you aware of yourself as a very controversial public figure in Argentina?

B. No, I don’t think I am, I don’t think of myself as a public figure.

M. G. But you are. You are featured in magazines, newspapers. T.V.

B. Yes I know but I don’t like it.

M. G. Everybody knows you. They don’t know your work so much.

B.Yes, true. But I don’t like it. I’m an individual. I think it was Spencer who wrote man versus the state. I think of the state as an evil, perhaps a necessary evil. I hate nationalism. This country is full of nationalists. I hope things are better in Canada.

M. G. Somewhat better, but there, too, the monster of nationalism has raised its ugly head. There’s talk of separatism in the West, and of course in Quebec, the French people have felt they’ve been oppressed for a long time and…

B. It’s a pity really.

[“Hola no, el senor Borges esta ocupado” — “No, Senor Borges is busy now…”]

B. When I was in Canada. People talked to me about Pratt. Is he a good poet? He has written a poem called “A Block of Ice” and an ode to something or other…that doesn’t sound promising does it?

[ Crunch, crunch]

M. G. I teach poetry and I want to ask you about Blake. His poem about the tiger and your own. Are you consciously echoing his tiger image in “The Other Tiger.”

B. I think “El Otro Tigre” is quite a good poem. I’m very fond of Blake (he whispers, and probes into his bowl again). I was always drawn to the tiger; as a boy I would seek out the tiger in the zoo… And in my dreams I’m never able to conjure up the desired creature…

M. G. The tiger… the labyrinth… the mirror… the dagger …do you consciously work these archetypes?

B. No, I do my best not to meddle with what I write. I’m passive, and then things come to me and after that of course I have to tinker away [laughs] lay them into shape.

M. G. Shaping through language?

B- Yes, of course. I think English is a far finer language than Spanish. One can do many things in English that are not allowed by Spanish. Reading “The Battle of East and West” by Kipling, there’s an English officer who’s pursuing an Afghan horse thief and they ride all night long the Khyber Pass in Afghanistan, then come these lines (Borges pauses, his voice becomes dramatic and he recites) “We have ridden the low moon out of the sky, their hooves drum up the dawn.” Now, you can’t ride the moon out of the sky in Spanish, or drum up the dawn because Spanish doesn’t allow it. It can’t be done. Or, for example, dream away your life. Shake somebody off. Fall down and pick yourself up. Live up to some things, have to live down. Those things are possible in Germanic languages. That can be done, I suppose, in the Norse languages, and in German or in Dutch, or in English of course, but not in Spanish, Portuguese, Italian or French.

M. G. Is there anything, you think, that can be done in Spanish and not English, particularly in poetry?

B- No, I don’t think so. Spanish, French have been carefully worked over. Spanish… nothing much can be done with it. When I think of Literature, well, I think of Dante’s Commedia, a great work by a Roman Catholic. I’m from a very mixed stock. My grand mother, she was Norse country. She came from North Cumberland. She was Church of England. Her forefathers were Methodist preachers. And my mother was a good Catholic. And my father was an Agnostic, or a free thinker. He had no use for a personal god. Personally, maybe I’m religiously minded, but I dislike it, well…

[“Hola si como esta?” “Hello, how are you/”]

M. G. Would you say your concept of eternity is Platonic?

B. Yes, in Christianity I can’t bring myself to believe in a personal god. I can’t do it. Besides, in this country, at least, being a Catholic doesn’t stand for beliefs. It stands for being a nationalist, for hating Jews [pained exclamation]… For being, well, a conservative. Catholicism in this country has hardly a religious background to it. You think of it more as politics.

M. G. Don’t you think there’s been a change in the last 20 years [since I lived there]. It seems to me society as a whole has become much more consumer oriented and hence material accumulation is more important than beliefs…

B. At the same time today we’re a very poor country. This is one of the most expensive cities in the world. We can hardly make both ends meet.

[The honk and squeal of traffic below on the street rose and jolted us into the present]

M. G. The historical references in your stories. are they facts or imagined accounts?

B. Well, sometimes they are fancied. But of course I have been a long time in this country. I’m one of the descendants of Cabreo. My grandfather fought with the Spanish. He took over the winning of the West which we call “la conquista del desierto.” My grandfather fought with the red Indians, the Pampas Indians…

[Crunch, crunch…]

Indeed Jorge Luis Borges seemed in himself to be a measure of time and timelessness, of Argentina’s history and myths. He marked the turn of the 20th century by his birth and bridged over the span of other periods and places in his stories as well as through his ancestry. He equated his military forebears with his yearning for an epic destiny, which he believed “the gods denied him, wisely no doubt,” but which are brilliantly and often longingly rendered in the mythic scenes of the gauchos, the Pampas and the knife wielding “compadritos” — or Argentine outlaws– conjured up from stories, memories, and dreams. His European heritage, the culture of the old world, on the one hand, and the open raw frontier of the new world, on the other, provide the scope of place and time, and the scenarios of the Borgesian stories.

M. G. When you were a young man did you have personal experience of knife fights, the old ritual of the gauchos?

B. No, but I met many in Palermo who were knifers, these things…

M. G. Militarism is a theme that runs through your stories…But it seems to me to be the fascination with what it is to be a man…

B. Yes but… the fascination with the knife fights… My grandfather fell in action in a small civil war in l874. My great grandfather fought the Spaniards. He was in the last march of Independence. He was a soldier of San Martin, then of Bolivar. Colonel Suarez.

M. G. When you were growing up in Palermo. You talked about living in the garden but being concerned with what was going on beyond.

B. When I was a boy I was not interested in those things. I was interested in books… And now I think both are wrong.

M. G. Do you feel you’ve changed?

B.Yes, I have

[Phone rings again: “Hola si mas tarde por favor…” — “Hello, yes, a little later please.”]

[Housekeeper interrupts removes the breakfast dishes]

M. G. I notice the many books by southern American writers on your shelves.

B. I know the southwest. I greatly love Austin Texas. I went to San Antonio. I saw the Alamo. I may go this year. I’ve been made a professor, honoris causa in Dallas. I love Texas… their history is more or less our history. The cowboy and the gaucho. We fought the red Indians, the Pampas Indians. They had the Mexican War, we had the Guerra del Brasil. We are traditional horsemen. Riders.

M. G. Do you ride?

B. When I was a boy I did. I was quite a good rider and a good swimmer also. I’m very fond of swimming and riding. Then I used to go for very long walks.

M. G. What do you fear?

B. Fear travelling for example. Twice on a plane I thought the whole thing might go to smithereens. Hunger and thirst. Death no. I look forward to dying. It may be an annihilation. It may be, let’s say, another dream. In any case, it’s very interesting.

M. G. It’s one of the recurrent themes you like to write about, is it not?

B. Yes, I suppose death is a major experience. I don’t know anything about it. Maybe it has a different taste to it. There’s a sense that people know when they are about to die.

M. G. Were you here when your mother died?

B. Yes, I’ve seen many people die. And they were all very impatient. They wanted to die. I remember when my English grandmother died. One of the last things she said. We went over to her bedside. She was dying and she knew it. She said well, she had forgotten her Spanish, she went back to English. She said to us “This, what is happening, is quite commonplace, an old woman dying, a very old woman dying, very very slowly. Nothing interesting about this. No reason why the whole household should be upset.” That means that she was brave. She saw herself as somebody else, an old woman dying very slowly. Nothing interesting about it.

M. G. What about your mother. Did she feel similarly?

B. Yes. She wanted to die. My father also. He died and he looked forward to dying.

M. G. Your father died much earlier did he not?

B. Well, let’s work out his age. He was born in l874. He died in l938, that makes him sixty or so. I’m not sure. My arithmetic is rather shaky. Let’s work it out… ’74, ’38. Same dates as Lugones. He was born in ’74; he committed suicide in l938.

M. G. Can you talk about an experience that was really significant in your life; that marked you in some way.

B. Many experiences. But chiefly, I suppose, well falling in love, then being crossed in love as all men are. And I think my chief experiences are of countries and of books. I always enjoyed reading. In fact, the chief event in my life as and still is my father’s library. Therein I read books I keep on reading now. I remember when I was boy, well, I read Kipling, Stevenson, Mark Twain, Poe, Henry James, Dickens, Lewis Carroll, Cervantes and so many more. I inherited my father’s library. I sometimes think I have never strayed outside that library. The Arabian Nights of course… [He points to the wall bookcase behind him]… is supposed to be the first edition. Captain Burton’s

M. G. Do your friends read to you?

B. Yes, since I lost my eyesight for reading purposes way back in l955. When I was made director of National Library. I wrote a poem about that…The magnificent irony of god who gave me at the same time books and the night. “Me dio a la vez los libros y la noche” [He recites].

[Borges gets up and motions me to follow him.]

B. G. I have something to show you.

[He held on to my elbow and escorted me to his bedroom.]

Look, see that bronze head of me a sculptor friend made, it’s big and weird enough to scare you. So that’s what I do to the housekeeper’s boy when he misbehaves. [Borges laughs at his prank. ]

Come back tomorrow and we’ll go for a walk in plaza San Martin.

The next time I met Borges he was having lunch, and while he waited for his meal to cool I asked if I could take a picture of him. Certainly, he said and we moved to the balcony of his third floor apartment; the light was rather dim in the room probably taken up by the mural size paintings of his sister, Norah, on the walls and the wall-to-wall bookcase in the small dining room. When we returned to the table, he took a mouthful of his plate and complained peevishly that I made his chicken get cold. Surprised by his reaction, I told him about my dream the night before in the house were I had spent my childhood, feeling as if I had stepped into the past. In the dream I was awakened by the grunt of large bulls trying to get in throughout the window somewhat ajar and which I tried to close by pushing the bulls back. Borges listened then said. “You are very brave.” And so we were back on track.

M. G. What can you say about South America?

B. Nothing really. We gave the world, well, a few names Bolivar, Pampas, Brazil, the Amazons…

M. G. Tango?

B. Well, yes, but the blues and jazz are far better than the tango, no?

M. G. Did you hear the blues when you were in the States?

B. No, no, no I heard them in Buenos Aires. Many people were crazy about the blues here and jazz of course is very important to us. The tango, well, after all bueno…The tango was invented in the l880s in the bawdy houses. In the case of the tango, it has the piano, the flute, the violin, the bandoneon…

M. G. Isn’t there a similarity between the tango the milonga and the blues. It is a cry a lament is it not?

B. No, no, in the case of milonga, it is not supposed to be. On the contrary, it’s supposed to be happy. And the tango, well it declined when it was known in France and then it became very sentimental. It is an erotic dance, well, played in the bawdy houses. Very complicated…

M. G. Do you like any particular blues or blues’ singers?

B. I know many blues by heart. I’m rather unmusical. I think of “Saint Louis Blues,” ” St. James Infirmary. “Do you know it?

[Borges sings] “I went down to St. James Infirmary I saw my baby there.” That’s very fine, one of the finest I should say. Well, so many others. There was a man, what was his name? Well, my memory is failing me, failing me all the time! You know, I have no memory of my own life. At least I have no dates, I have very vivid images. Let’s say of Egypt, I was blind when we went there. And Japan, for the first few days we were at sea…My memory is full of verses in many languages. Now I’ll say something to you that you know by heart then you tell me what it is. You know it by heart!

Borges quotes in a rich deep voice “our Father …” in old English, Anglo Saxon that is.

B. In English there are some Norse words left by the Vikings, for example if you say “they” that comes from Danes, Saxons said they’d…the word sky is also Scandinavian

[Clatter of plates in the kitchen]

M. G. Can I ask you a question about film?

B. Yes, I want to say this. They made a film about a story of mine called “La Intrusa.” I saw many films of Joseph von Sternberg Dragnet, George Bancroft, William Powell. The Showdown, Underworld, The Doctor of New York. They were all gangster epic films.

Citizen Kane… Before my blindness I was very interested in films; I wrote reviews for magazines on Chaplin, Orson Wells, Eisenstein. I was particularly fond of Hitchcock and Westerns. I think Hollywood has saved the epic in the modern world. I think America and Argentina have similar mythic beginnings. The stories of the cowboy and the gaucho have common roots in the wilderness, and in their heroic survival in it. They are both fighters and riders, often rebellious outlaws which makes them blood brothers,

M. G. What about Argentinian Films?

B. Oh, they’re beneath contempt. Quite bad ones. Brazilian films are far better. Don’t say Argentinians, say Argentines. Argentinians is a fancy word. I wonder who coined it?

M. G. Outside Latin America people don’t seem to know much about Argentina.

B.Yes, of course they think us as being Mexicans or Spaniards.

B. We have a disadvantage in this country, I mean this is white man’s country and a middle class country, and both should make for good. I don’t think they have. When I was in Peru, in Ecuador, in Colombia I found a few wealthy people, all the rest of the populations were paupers.

…I never think in terms of money. I find that rich people are apt to be mean. I think that poor people are generous. In this country nobody is well to do! I think in this country we are going to the dogs. This country is declining and falling, and not just this country but the West. Der Untergang des Abendlandes [Oswald Spengler’s Decline of The West] “The going down of the evening land. “German is a beautiful language!

There’s a long contemplative moment, then Borges says that words are not only a means of communication but also magic symbols and music, rooted to a common ancestry and mythology.

B, Let me tell you something about your name Mara that you may not know, in Hebrew it means bitter, in Buddhism it’s linked to temptation…

M. G. In Latvian it is the name of the pagan goddess of fecundity.

B. Ah yes of course. And now let’s take our walk in the plaza.

His voice grows ponderous, heavy. He stands up, and so does his white cat Beppo stretching to take up another position. Borges reaches for his Chinese bamboo cane and turns towards the door and once again this giant of the mind shrinks back into a frail old man like a marvellous genie from The Arabian Nights. I offer him my arm.