Hōshanō:[1] how to portray an invisible enemy

Hideki Kawashima

An interview with curator Amandine Davre and artists Michel Huneault and Ai Ikeda[2]

After the triple catastrophe in the Tohoku region of Japan in March 2011 – the tsunami, the earthquake and the ensuing explosion of the Fukushima Dai-ichi power plant – curator Amandine Davre, who had already been interested in Japanese art for a number of years, decided to focus on the representation of the nuclear imaginary.

For this project, Hōshanō: Art and Life in a Post Fukushima World, her goal was to open a dialogue of divergent perspectives between Japan and Québec, where (like anywhere else today), the danger of radioactivity remains a silent, intangible presence.

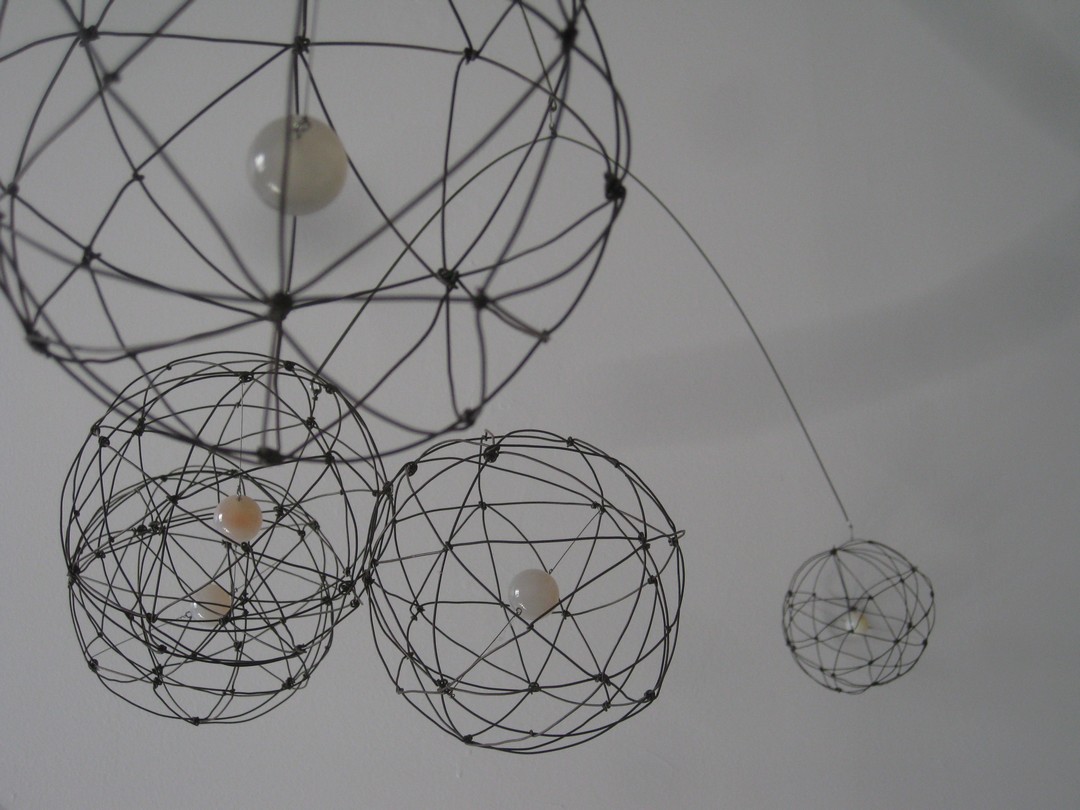

The exhibition shows the work of four artists: Ai Ikeda, who became interested in radioactive contamination and its effects on the human body after making a return trip to Japan (from Montréal) three days after the tsunami and Fukushima incident occurred on March 11, 2011; Stephen H. Kawai, whose mobiles representing atoms and radioactive particles portray the common ground between art, technology and science; Hideki Kawashima, also based in Montréal, whose installation invites visitors to open their eyes and see into the darkness; and Michel Huneault, who transitioned from academic and humanitarian work into art, in his quest to find more effective forms of representation to convey the insights of his fieldwork to a broader audience. Huneault had documented the oil explosion following the train derailment in Lac Mégantic in 2013.[3] Not long before that, he had travelled to the region of Tohoku in 2012, and decided to return there in 2015-2016. Eight of his photos and the video 10 minutes at Tohoku can be seen in the show.

Stephen Kawai, Atomique

Stephen Kawai, Atomique

Can you talk to us about the title of the exhibit?

Amandine Davre: Hōshanō is the Japanese word for radioactivity, but it is like a taboo term in Japan. It is too painful to use, except in the context of a public-awareness campaign designed for its shock value. I decided to include it in the title because I wanted it to retain its secret, hidden quality for visitors, like radioactivity: invisible.

How did the exhibition take shape?

Amandine Davre: I put out a call to artists at Concordia University, with the help of Hideki Kawashima. I was already in touch with him and Ai Ikeda. That went well, but once my dossier was ready, many galleries refused the project. My topic wasn’t commercial enough; it was too political, too difficult, until Bettina Forget from Visual Voice Gallery, a space that highlights the connections between art and science, opened her doors to such a difficult topic.

In parallel, I organized an international symposium at the Université de Montréal, about the history, the aesthetics, the imagined views [l’imaginaire] of the nuclear, which concluded with a visit to the exhibition on the anniversary of the triple catastrophe.

Nuclear aesthetics? Could you please clarify?

Amandine Davre: There is the question of how to make radioactivity visible, of representing it, of rendering it in a way that it can be more readily acknowledged. I was drawn to study censorship in the aftermath of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the ways in which artists dealt with it. And then there is also the idea of the atomic as awe-inspiring [le sublime atomique]: the mushroom cloud, for instance, was at the same time magnificent and horrible.

And just how do the artists in the exhibition address these issues?

Ai Ikeda, Sievertian Human – Wisdom, Impression, Sentiment (2017)

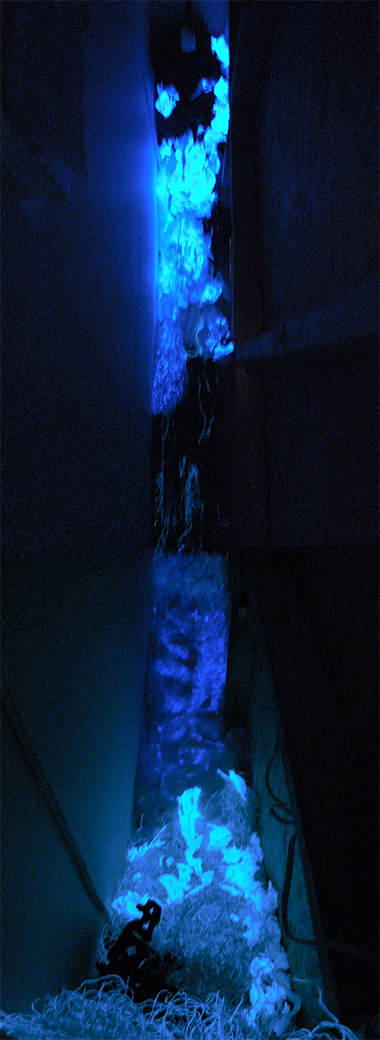

Amandine Davre: In Ai Ikeda’s piece entitled Sievertian Human – Wisdom, Impression, Sentiment (2017), the numbers you see on the left indicate the time it takes for radioactivity to disappear (from the human body): 24,000 years after the person has died. Kawashima’s installation, 60 seconds – Extinction (2017), on the other hand, is able to recreate, with the lights off, the particles that our eyes do not detect but that nonetheless surround us.

Michel Huneault: I was on the coast of Tohoku, and it was a perfect spring day to do photography – sunny, with a nice breeze. It was a golden hour on a seaside landscape in the empty town of Odaka, and I had almost forgotten about radiation when the speakers that play music in public spaces in many towns in Japan started playing tango music. To no one. That’s when I realized that the invisible danger had hidden behind the beauty of the landscape. Now how do you represent that? I didn’t want to dwell on disaster porn. I wanted to make people feel what I felt, to recreate that sense of place.

Michel Huneault – Nature takes over an abandoned carwash in the Odaka district exclusion zone, approximately 15 km from Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant (2012)

Michel Huneault – One thousand origami cranes, for best wishes and good luck, facing the zone devastated by the tsunami and being rebuilt in Onagawa (2015)

When you experience that sense of place, your understanding deepens, and it puts you in a better position to contribute more relevant solutions for the future.

Michel Huneault – A Chinese quince tree (known as ‘Karin’ in Japan) in the Odaka district exclusion zone, approximately 15 km away from Fukushima Daiichi (2015)

Could you talk to us about the image of the quince tree?

Michel Huneault: While the scope of this work extends beyond Fukushima in order to cover 300 kilometres of the coast in the Tohoku region, that image is from a place within the exclusion zone, 15 km away from Fukushima. I was driven to the tree because it is so unusual to come across such a well-kept tree with fruit on the ground. It was bizarre to know that people kept coming to take care of their house and their garden, but they were not going to pick the fruit, or eat it…

I remember the expression on the faces of some people who were fishing in the exclusion zone, when they witnessed my surprise that they were fishing. They just looked at me as if to say “What difference does it make? This is where we live and it’s everywhere around us,” as if they had decided to force their minds to forget about it.

This brings us to two of Ai Ikeda’s pieces, which focus precisely on memory.

Ai Ikeda, Atomic-ity #1 and Atomic-ity #2

Ai Ikeda: After Fukushima, it became clear to me that there was a problem with memory in Japan (oblivion of the past), and that this had opened social wounds about the nuclear past of Japan. In my recent art works, the representation of memory is used to question and rethink new meanings about the nuclear imagination.

Persistence of Memory – Radiation Exposure Remains, for example, reminds us that despite the process of historical repression in the face of the anxiety of the past, the impact of irradiation on the skin and biological tissues persists. And even after the body becomes ashes and dust, the nuclear materials remain.

Is this “problem with memory” and “historical repression” in Japan behind the fact that neither of the two artists from the Japanese community in the exhibition is currently living in Japan?

Amandine Davre: I believe that assessing this issue while living in it has to be very difficult. On the other hand, I was looking for a view from the distance, an external look, one that would be liberated from any form of censorship or control. When I’ve spoken to friends in Japan, I’ve realized that they don’t have access to the same information.

Ai Ikeda: As I was beginning to gradually form a more informed understanding of modern and contemporary art, philosophy, and critical theory, the tsunami and Fukushima nuclear disaster happened in Japan in March 2011. The disaster changed my perspective, and I realized that my perception of Japanese society and international relations and politics was becoming more critical. It became clear to me that not only could art be used to affect people and inspire them to help others, it also had the power to stimulate social debate and even lay the groundwork for social change.

Can you talk to us about the physiological aspects you portray in your piece, Internal Radiation?

Ai Ikeda, Internal Radiation Exposure – X-raying

Ai Ikeda: One of the effects of radiation exposure is chromosomal abnormalities or aberrations, which provoke the chromosomes to connect erratically or split repeatedly, causing illness such as cancers. This work makes visible the world of the inner radiation exposure, by evoking a microscopic observation of a specimen prepared on a glass slide on an X-ray view box.

Is this a post-Fukushima world?

Amandine Davre: For me there is indeed an after-Fukushima and it is important to take it into consideration when making decisions. I borrowed French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy’s idea of a civilizational catastrophe, because that is to me what described Fukushima. I would like it to be a lesson for the whole world.

Hideki Kawashima, 60 seconds – Extinction (2017)

The exhibition runs from March 9 to April 15, 2017 at the Visual Voice Gallery (Belgo building).

372 rue Ste-Catherine O., Montréal

(514) 878-3663

http://www.visualvoicegallery.com/portfolio/current/

On April 13, artist Stephen H. Kawai is scheduled to participate in a symposium at Concordia University, exploring the influence of art on academic research.

[1] Radioactivity

[2] The interview was conducted in French (with Amandine Davre) and English (with Michel Huneault and Ai Ikeda). For logistical reasons, the latter answered our questions in writing.

[3] https://www.schiltpublishing.com/publishing/authors/michel-huneault/