Jaspreet Singh drips tomato juice from his lips and sucks on mangoes, in a delicious and intricate exercise in culinary commitment and infatuation with an unrequited sexuality that runs through his new novel, Chef. Nearly every chapter if not every other page recounts the brush of a fumbling non-performer, the chef-in-training, with the dominationist sexual advances of a counterfoil character, male or female, while the political and debilitating complexity of India, Kashmir race through the novel in all its bleakness. Cuisine as sexual metaphor, the act of preparation of food, as foreplay, has been used indiscriminately over the years both in fiction and cinema, but Jaspreet uses it with a delectable north Indian ecoutez-moi bien rudeness. A precision military foulness makes gali (abusive language) depravedly sexy, lucid and yet poignantly craving for secularity in the cultural mess that is India. Nothing vibrates more in India’s cathartic duel with itself, than the sexual metaphor of communities screwing each other and deriving absolutist pleasure out of it. And the majority Hindu community excels in berating, deriding and generally second-classing all others including of course Muslims, and then Sikhs and then Christians and so on and then lamenting the loss of Kashmir to Pakistan-inspired militants.

The forlorn beauty of Kashmir, so often depicted in photographic essays, has never been portrayed so elegantly as in this novel. And being a despondent Sikh, Kirpal or Kip, the sous-chef on the rise, portrays Kashmir with an intelligent sentimentality. In the final analysis, India’s attempts to cling on to Kashmir while endlessly and brutally controlling its people has led to all the mindless acts going on in India, including the latest carnage in Mumbai. Jaspreet Singh meticulously portrays the nearly silly and decadent lifestyle of the British nurtured colonial Indian Army, whose class hierarchy and servant-lord dichotomy remains an impediment to its ability to perform and in effect be taken by surprise by both the Kashmiri militants and the Pakistani military’s hide and seek games.

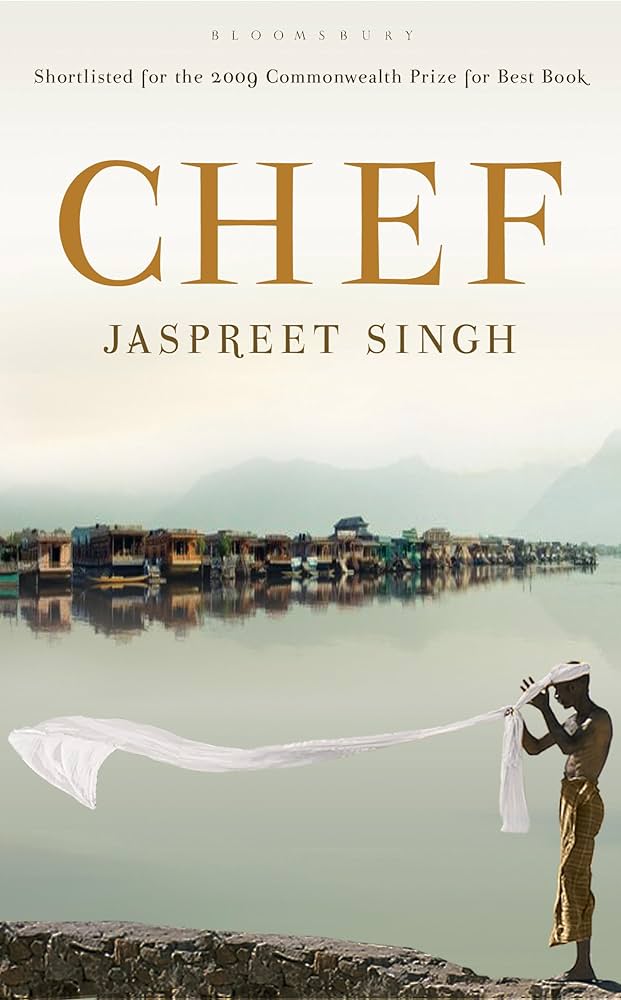

Somewhere in the Siachen glacier in a dark cavernous black hole, aptly illustrated on the cover, the Head chef ultimately douses himself in kerosene and takes his life, somewhat inexplicably. A suicidal “screw you!” act that could have been better developed.

In essence, an excellently luscious novel that fritters away towards the end with the hope that newer and younger people with intelligent secular notions and a sense of poetry could perhaps turn the tables on the colonel-sahib/saffron nexus that has occupied the Indian mindset towards Kashmir.