Preface

As our editorial team was brainstorming ideas for this issue’s theme on heritage, I kept thinking of La Meute, a white nationalist/white supremacist group in Québec that proudly calls itself “The Pack.” Like its chilling counterparts in English Canada, the US and other parts of the world, La Meute’s official line is that it’s not racist or anti-Muslim. It is merely defending its legitimate patrimoine[1] – its heritage harking back to its white European roots (in this case, in France).

I was also thinking about the Indigenous women in the remote community of Val d’Or who, with the steadfast and painstaking support of the Val d’Or Native Friendship Centre, gathered their courage and stepped forward to denounce the intimidation, abuse of power, and physical and sexual abuse they suffered at the hands of some Québec police officers. After learning that no charges had been laid against the officers, eleven women wrote:

What we ask for is true justice: justice for ourselves, justice for our daughters, justice for our grand-daughters…

What comforts us is that we know we are not alone. And today, we solemnly call upon all the Quebec people, Aboriginal and non Aboriginal, to extend a helping hand to Indigenous women so that we may create the strongest support and solidarity network ever.

This is also what gives us hope, a new hope.[2]

In their situation of extreme vulnerability, the strength of these women’s vision of a vast community of support got me wondering. What are the words in their mother tongue – their rightful matrimoine – for the heritage they dream of? What are the words that call us all together and lift us up?

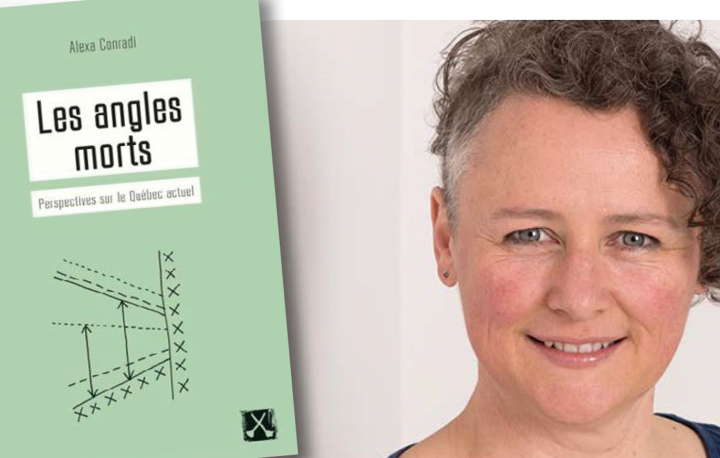

The words of Alexa Conradi do exactly that. A courageous “shift disturber”[3] (i.e., whose words and actions call for a major shift in perspectives), Conradi challenges Québec’s racist and misogynist colonial heritage, and plants the seeds for creating the kind of solidarity-based community and society that the women of Val d’Or invoke.

Alexa Conradi has been a feminist and social-justice activist in Québec for the past 20 years – one who challenges the ravages of austerity policies front-on and stands with all those whose lives have been made more precarious. She was president of Québec Solidaire in its early years from 2006 to 2009, helping shape its social democratic, environmentalist, feminist, LBGTQ and sovereignist program. From 2009 to 2015, she headed the Québec Women’s Federation (QFF), which took a lot of heat – and hateful vitriol – for its solidarity with Muslim women and its opposition to Québec’s Charter of Values.

Conradi’s new book of essays, Les angles morts, Perspectives sur le Québec actuel (Les Éditions du Remue-ménage, 2017), is intended to do some serious shift disturbing. Conradi interweaves the personal and the political as she invites her fellow Quebeckers to take a good hard look at their blind spots. Time to tear off the rose-coloured glasses about how egalitarian, fair, welcoming and non-violent Québec society really is.

The following interview with Alexa Conradi is a slightly abbreviated version of our conversation.

MS: First of all, congratulations! We just heard the news that your book has been nominated for the Political Book Award presented by the Québec National Assembly. Did you have any inkling that it might be considered for an award?

AC: Absolutely not. I certainly didn’t write it in terms of awards or recognition. I wrote it to be able to think through the unbelievable, unique and sometimes difficult experiences of the position I have been in, which gave me access to people, events and possibilities in ways that very few people have access to in the course of their lives.

I was more motivated to look at the times we’re in, really. The question of recognition is an important one, and one that I’ve struggled with, because as someone in a minority situation but nevertheless at a privilege in Québec society, I haven’t been able to completely free myself up from the wish to be seen, heard, understood and recognized as being part of the society. I didn’t write with awards in mind, but I’m not completely outside of the wish for the book to resonate meaningfully with people in that society and reclaim a space inside it. So it’s not so much about rewards and awards as spaces of mutual understanding. That was something that did drive the writing of the book.

MS: A great deal of research and reflection, first-hand experience and soul-searching has gone into this book, which covers almost every angle (!) of what has happened in Québec since the Quiet Revolution. It is a tour de force of historical, political and feminist analysis and reflection that offers us a feast of thought-provoking ideas and insights.

You cover a lot of ground. Your book raises hard-to-duck criticisms while showing a lot of love and respect for your fellow Quebeckers of all backgrounds. You clearly embrace bell hook’s perspective on “love as the practice of freedom.”[4] What does she mean by that? How do we go about cultivating movements that are anchored in an ethic of love? And what does love have to do with it when we are up against such systemic violence?

AC: To be honest, I can only say that’s an unresolved question. In the world of struggle, the changes or aspirations that I’m talking about in the book require envisioning but also tremendous struggle. And in the face of violence, struggle, non-recognition and experiences that people have of being completely excluded, or huge moments of injustice, it’s very hard not to get tight and cold, defensive, angry, bitter.

It’s very difficult to sustain a sense of wonder and joy in the middle of so much pain and struggle. And so, when I was working through some of the struggles that I think were personal but at the same time very collective in many ways, I myself went from “oh I’m feeling angry and bitter at people, at situations, at the world, and that’s not a place that I find I can survive from. I can’t blossom, I can’t grow, I can’t breathe, if that’s the main feeling” to somehow thinking, “ok, how do we change up some of what we do? How do we think it through and organize collectively in a context of struggle?” Not a kind of naïve idea of change, but in a context of struggle, how do we sustain that, how do we create something that is spiritually and ecologically sustainable for individuals and for life?

I’m not sure I have answers to it, but we need to have those conversations and make that a subject of our discussions and our practices. So instead of coming in with a recipe of “ok, here are the 10 ways to do that,” that’s not even really a discussion. And when there is a discussion of self-care, for example, it’s from a very individualist perspective and takes a kind of neo-liberal approach, almost. So in talking about the conditions under which we organize, how we organize and how we think about how we bring about change, this needs to be a subject of discussion. It needs to be present.

What does love mean in a situation like that? It’s not a flowery “let’s just step above how we feel, how the anger, the injustice feels,” as if those feelings aren’t real. That’s not what I mean. I mean some kind of openness and vulnerability and trust, at the same time as risk-taking and claiming our strong feelings of anger and sense of injustice, but in a way that is more acknowledged. [I mean] somehow loving – finding a way to acknowledge the pain and trauma – in the way we organize and think about mobilizing and social change movements. If we were to acknowledge the power dynamics and how much energy it costs us to go through these things, maybe we would do better at looking after them as a group.

When we get together, we would figure out what we need then, acknowledging the cycles and rhythms of the world of nature. We have four seasons; we have night and day; we have hot and cool times of the year. And those are completely disconnected from how we organize ourselves politically. That makes no sense. I think we’re coming actually to the end of a time, a whole era. We’re coming to an end of it. There’s an end of a cycle, and both environmentally speaking and socially speaking, the pressures are everywhere. Capitalism is reaching certain kinds of limits. It has an incredible ability to reinvent itself, but nevertheless, ecologically, we’re coming to an absolute limit. I somehow believe that this idea of love is deeply an ecological concern, too, in a spiritual and connected sense to one another. I know that’s not a short or very coherent answer, but it’s what I’ve been trying to think through.

MS: The existence of systemic sexism in Québec is not that difficult to discuss, thanks to feminist debates dating back to the 1970s. But engaging in civil debate about systemic racism has become almost impossible in many circles in Québec, and politicians engaged in xenophobic nationalism have shamelessly fanned the flames of demagoguery that stifle reflection and self-questioning. As you point out, the divide between Quebeckers of diverse backgrounds and those of French-Canadian descent has become deeply entrenched. What’s it going to take, do you think, to break the impasse we’re currently facing and go beyond knee-jerk denial and defensive evasion?

AC: Today there are a number of different types of possibilities that could really make a difference. First, this tendency in Québec is situated in a pretty Western tendency at the moment. Québec has its own particular history and its own particular form, but all over Europe, for example, we’re in a time where people – where many white people – are feeling anxious and expressing that in very racist terms.

So, Québec is not an exception. But in terms of possibilities for the future, one of them is that younger people aren’t showing as much racism as an older generation of people. We have to remember that the ones discussing in the public sphere are not the only voice out there. Politicians who hold power are usually much older, usually white, and usually more established, let’s say. They’re not necessarily always a good reflection of all people’s sentiments. And that goes for media people as well. If you look at who are the commentators in media, they tend to be older white men as well. We have to be careful not to take their voices as being the truth.

There is some incredible organizing in Québec at the moment around anti-racism work, led by people of colour – black folks and Indigenous people, and Muslims as well – and they are doing a lot of really important work of making connections in places that are fairly invisible to the media or to the public discourse. But it’s happening and it’s making a difference. After the launch of my book, I had twenty-five stops all across the province and met with people who are concerned about this rise in racism in Québec society and the consolidation of certain racist sentiments – the freeing-up of racist speech. And that was in every region: people who are willing to get organized, think about it, speak up against racism and get involved. That’s encouraging.

And at a much more difficult level, this [intensification of racism] is something that happens typically in a time of tremendous economic insecurity. This happened in the ‘30s all across the West, and it’s not surprising that it’s happening now after years of neoliberal policy. So I think that anti-racist work per se, in and of itself is absolutely necessary. It’s also necessary to keep in mind that racism gets worse under neoliberal and economically insecure times. So when governments speak about prosperity – and you know, the Québec government tends to speak about being great at job creation and about having sustained prosperity since it’s been in power – at the same time, people’s work is more and more unstable. It’s insecure, it’s part-time, it’s on contract, and we’re living in times where the idea that one can make a decent living from one’s work is not a given for many, many people. The social safety net is no longer a given either.

Those two things, combined with other kinds of insecurities like free trade, global transfer of companies to different places around the world, and all that kind of competition that pushes people’s working and living conditions down – all of that combined makes people’s sense of security fragile. And unfortunately in the history of white people, that has often turned into racism and that type of insecurity.

That’s a really important piece. There are many people in black communities, for example, who say that working with white people is exhausting, and they would prefer to focus their energies on lifting up black people. That’s an absolutely fair response to racism. Those of us who are concerned about this question have a responsibility as white people to talk to other white people. Québec has the advantage of having very powerful, very deep-seated organizations across the province in ways that are quite unique – and more and more of these organizations are taking some responsibility for the discourse around Indigenous people. That wasn’t true when I first got started.

And there are more and more organizations that are ready to take up some of the questions around systemic racism and anti-Muslim racism. I think anti-Muslim racism is one of the hardest ones because of the relationship to religion.

Those are some of the ways that we need to be working on. But ultimately there needs to be a kind of acknowledgment in these organizations (which are so important in Québec society) that there’s actually a problem. Some are doing it and many are not. That’s one of the big challenges: how do we move forward with an acknowledgment in civil society – or uncivil society – of how to think this through?

Each sector needs to think about it. If you work in health and social services, what are the ways that systemic racism plays out, and then how do you integrate that into your work? This [kind of questioning] is not necessarily happening. You know, the unions aren’t necessarily thinking about it in those terms, nor are community groups. They may think about systemic racism in terms of access to jobs. They might not think about it in terms of “how is it that people of colour are received in our health and social service system with unconscious bias against them? How does that play out? And how do we train our people to work differently?” We’ve got a long way to go.

MS: Your book alludes to the Black Panther movement, Angela Davis, and the teachings of Malcolm X and James Baldwin on the importance of decolonizing the mind. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s hearings, the inquiry hearings into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, the #MeToo, #BeenRapedNeverReported movements, the Black Lives Matter movement, the earlier Idle No More and Occupy movements, and the protests for a decent minimum wage are like a vast, sprawling truth-telling caravan.

Decolonizing our minds is an on-going process, and your book incites us to re-examine our default positions. Since it was launched last fall, what kind of feedback have you been getting about readers’ willingness to undertake this kind of personal and collective introspection?

AC: What comes to mind is a woman in the Gaspé, who organized events there so that I could meet people and we could talk and think about the book. She was blown away by the book and found it both extremely confronting and challenging. She works in a women’s centre […] and she has made sure that they’re having an on-going conversation in the centre about how to take up some of the challenges that are posed by the book. She also wrote a piece for all the other women centres, saying “it’s time that we do this work.”

That’s the kind of feedback I’ve had on it. I’ve also had CEGEP [Québec community college] professors write and say that they’re using this book now in their philosophy courses, for example, because it gives them both a theoretical and a practical “in” to think about questions that are deeply philosophical. It’s really encouraging that people see the use and relevance of having students read it.

And then I recently had a young girl of fifteen who wrote to me saying that she’s a feminist and for her, the book was really an eye-opening experience.

A philosophy professor at a university, who is a black woman – one of the rare black philosophers in francophone Canada, let’s say, in Québec – said that in reading this book, she felt that I had been listening to black women. If a few people like her and like some of the Indigenous women and Muslim women who are out there, leading the way, feel like they have a bit of an echo chamber with this book and feel supported by what it does, then it is also contributing somehow to the decolonizing process. Because that’s a dynamic, a relationship. We can’t decolonize by ourselves. We work on something together. White people who are in positions of privilege, like I was, need to show that we deserve to be trusted… and then it makes it possible for other people to say: ah, it’s possible to be heard; it’s possible to be understood; it’s possible to feel recognized by people in positions of privilege or advantage – you know, the white-patriarchal-capitalist bell hooks-style reference.

MS: In your book, it’s clear that you have been deeply committed to the cause of Québec sovereignty, despite having been the target of wrath as a feminist leader committed to defending minority rights, particularly those of Muslim and racialized women and Indigenous communities. The narrow way that the national question has been framed for the past quarter century has made it difficult for many progressive Anglophones and Allophones in Québec to align with the sovereignist movement (even the more inclusive Québec Solidaire). So much energy is going into fruitless and hurtful debates that divert our focus from essential issues. Social justice issues are regularly getting pushed to the side. Neoliberal forces are placing the population and the environment in an increasingly tenuous position. Given our current political structures, how do you see us moving forward in Québec, building greater social solidarity?

AC: What I’m trying to argue in the book, I think, […] is that it’s possible to have a fairly integrated struggle against forms of domination, where one takes into account the effects of capitalism, the effects of patriarchy, the effects of racism, the effects of colonialism, and find points on which solidarity can be built. Here’s another example that refers back to your earlier question: someone from a bookstore said that he was afraid of intersectionality as he thought it was a divisive tool, but after reading my book, he saw that it could actually be a uniting tool.

You know, it’s not so much a theoretical concern around intersectionality; it’s a practical, political, organizing structure for me, in the sense that I think we could build coalitions that are moving, coalitions that form and de-form, but that commit to this anti-domination perspective. And that means really deeply having a feminist analysis of economic relations. It means having an anti-racist analysis of culture.

It means taking what we’ve learned politically as root causes of injustice, and then trying to build out together what that could mean concretely in terms of changes. But we tend to work in isolated ways. I think our times call for a less isolated approach. The environmental movement works on the one side, and social justice folks work on another side, and then feminists in another corner, and then anti-racists in another corner. For people like me and also for broad strokes of the feminist movement in Québec, I think, that’s too confining as a way of working, and doesn’t meet the struggles of our times.

Like I said earlier, we are living in a time that requires fundamental rethinking of how we build social, political, economic relations, because of the environmental disaster that we’re facing. And so I think it’s time to take a risk in how we organize politically, and try and find ways of building those lines of solidarity concretely. But none of those will be easy struggles. What gets called a women’s issue, to me, I never see as a women’s issue. I always see it as a society issue. And it changes the relationship that men can have to themselves as well, and to us, obviously. Or it changes definitions of gender; it changes dynamics of sexuality.

Same thing if we were to talk about environmental questions. If we were to completely rethink how we work the economy around production, what’s production, what’s socially relevant, what’s social reproduction, how do we rethink all of that? Well of course we need to think through, then, immigration. We need to consider what work then gets attributed to men and what work gets attributed to women… and who gets paid for what, and who gets recognized for what. These are things that to me seem so naturally integrated, but for social movements that have been organized in other terms, that’s not a natural approach. That’s not an automatic reflex. But I think we need to go there.

There would be a lot of strength there, but struggle, too, because it means changing ways of thinking; it means changing power dynamics; it means allowing other people to have things to say, who right now don’t have that power. There is a strong anti-racist movement in Québec, but they’re not where the coalitions are. And that’s because those coalitions have never really expressed an interest in taking seriously what they have to say. So, this work is very difficult work. And it has yet to be seen, for me, whether, with changes in dynamics within Québec Solidaire, it will be able to take up some of those challenges in a positive way. It has done some really good work but has not taken up such a role, and has avoided much of this [more radical program].

I think this is a more radical program, but not necessarily only in a classic Left/Right sense. It’s a more radical program to get to the deep-seated structures of power that create the kind of inequalities we’re talking about. I think Québec Solidaire is constantly in this mix between fitting within popular discourse and reflecting the goals and aspirations of a diverse Left. But that tension… I think most of the time they’ve looked for approval more than [going for] the more brave position, let’s say. But those currents are inside Québec Solidaire. It’s not like they’re not there.

MS: There’s also a kind of radical rethinking needed, of what we want work and non-work to look like, and how much time spent in work, and the lack of down time for a lot of people or too much forced down time because of unemployment. All of that is not really being addressed, like what our vision is of what would be healthy within our current resources and given our needs.

AC: There are so many different layers to it because, like you said, some people are highly overworked and there are people who are underworked, yet everyone has something to give to society somehow. So that even the concept of work… these are all questions that we need to be raising, because for many people these are balances of life somehow, being able to sustain oneself and one’s community: what do we need for that? That should be the starting point of the question: what do we need to have to be able to sustain ourselves and our communities and our earth? And then go from there.

MS: One of the last essays in your book invites us to rethink our relationship to the earth, and to reproduction, from a perspective that puts life and all that sustains it at the heart of political and economic activity. Building on ancestral Indigenous knowledge is central to this vision. Could you give our readers an idea of what the Buen Vivir movement is all about? And how would you say that in English: well living, or something like that?

AC: That’s it. It’s not the idea of “better,” it’s about living well. These are movements based in Latin America that have come out of discussions largely centred on Indigenous peoples’ histories, organizing, and struggles for recognition and decent lives inside Latin American countries. But it has translated in political terms into trying to find ways of moving away from a capitalist logic of governance and production to placing the sustainability of communities and the earth at the heart of how everything then flows.

This particular idea is a spiritual concept at the same time as a political one – spiritual not in the sense of a religious idea, but in a sense that ultimately we are all connected, all of us, every living creature, every part of life is connected, and so then we are highly responsible for those relationships. And that needs to be translated into how we organize ourselves economically, politically and socially.

And then there have been feminists organizing within this tradition to say: “in that context, we need to completely rethink production and reproduction and that division where production has always historically been associated with male labour, and reproduction with female labour that was highly undervalued.”

If we put the maintenance and the reproduction of life at the heart of things, then that actually changes the dynamic altogether of, and even our understanding of, what is productive. Instead of seeing production as being how many more products we produce, [it would be more about] “how do we look after one another properly?” That’s a very different logic. Of course, anyone can say, “yes, but that’s very naïve, a very Utopian kind of perspective.” But […] we can’t get anywhere if we haven’t thought about it – imagined it, thought about it, started to try and find ways to create it.

There are countries in Latin America that are starting to try and think this through, and they’ve given themselves the possibility of doing so at a structural level. We don’t have any of those mechanisms in Québec society or in Canadian society at this point, but that would be pretty exciting.

MS: There are some very powerful experiments in community self-emancipation that are unfolding in place like Jackson, Mississippi. Activists there are building what they call “solidarity economics.” They’re pooling resources, labour and community wealth, in combination with communal land ownership and agriculture and 3-D manufacturing. And they’re not limited to Jackson. They intend to take this movement and spread it through Mississippi and beyond Mississippi. There’s a book called Jackson Rising[5] that just came out last October. I don’t know of anything like this that is happening here or in Canada. This is coming out of the black community. I mean, we used to have community economic development projects here, but that wasn’t the same thing.

AC: I’m not familiar with this movement in Jackson, but are they coming out of a context like in Detroit, of complete collapse of the surrounding economic environment, and very little government support? You know, Québec society nevertheless still has a much more active social safety net than (I would think) Jackson, Mississippi. These types of initiatives tend to come out of collapse. And people’s willingness to think in new ways comes out of collapse. The challenge that I think we face in wealthy environments – which doesn’t mean that the individuals inside these environments are all wealthy – but the challenge we face is, will we have the impetus to make these changes in the face of tremendous [countervailing] interests […] and also, the difficulty in making changes unless we have to. Those are big challenges for more comfortable societies. Even though we have tremendous poverty in this society, […] the push for inertia is very, very high.

MS: Your book is grounded in the personal, in experiential life, and that makes a difference in terms of how readable and how touching it is.

AC: I was brought into the world as an activist, let’s say, through the feminist movement and through women’s centres. Through them, I learned that we are always in a relationship between an “I” and a “We” and an “Us” in the way we’re working. And I found this to be such a powerful tool to embrace consciousness, to bring solidarity, to make things real and concrete, to translate ideas and concepts into real life. Then later, in studies at the university level, I read about traditions in Latin America where, if people were speaking or giving a speech in a political moment, they would get up and say, “I am so and so, and I am part of this tradition,” and would move from this “I” position to very quickly situating themselves in a “We” tradition. You hear that with Indigenous rhetorical traditions, with black North American rhetorical traditions, and in the feminist tradition.

I find these very powerful ways to make shifts possible, but also to build an “Us” and a “We” that is not based on the domination of one type of discourse or a false universal “Us” that incorporates the stories of many different perspectives. That was a motivation in my activism and also in the writing, to keep that kind of a tension and a dynamic present. I wanted the book to be not so much for the academic world (although I think it still could be relevant for people studying), but written in a way that people didn’t go, “oh God, I have to get through this book.” I wanted it to be true stories and concrete situations, and real moments of possibility or tension that connected with my life but also the lives of other people whom I’ve met. So that was the reason for the form of the book. There’s always a certain amount of risk-taking in being so personal in public, but such is life. I’m asking lots of people to take risks, so if I don’t take any, it doesn’t make any sense.

MS: Your book is being translated, right? Do you know yet when it’s going to be coming out in English?

AC: I don’t know the publication date, but I would think in the fall.

MS: With your same publishing house?

AC: No, it’s with Between the Lines in Toronto. Between the Lines is a really engaged publishing house that does a lot of translation of books to keep the dialogue going between English-speaking Canada and Québec and French-speaking Canada, let’s say, to keep diversity of French in Canada visible.

MS: In closing, I’d like to acknowledge the compassionate and incisive kind of feminism that infuses your book. I find it heartening on many, many levels. Your imagination takes us deep into the wisdom of the ancestral land that sustains us, and far into the dreamings of life beyond capitalism. So I’d like to thank you, Alexa, on behalf of all of us at Serai, for sharing that with us.

AC: Thank you for those lovely words.

[Note: All photos in this interview, except for the one of Alexa Conradi and her book, were taken by Jody Freeman.]

[1] My hunt for a feminine noun in French that was equivalent to patrimoine as a term for heritage turned into a wild goose chase. The literal equivalent, matrimoine, means matrimony, of course, with no hint at a broader concept of maternal inheritance or heritage through the mother line.

[2] “Declaration of the Aboriginal Women of Val-d’Or,” November 17, 2017, published by NationTalk on November 18, 2016 – http://nationtalk.ca/story/declaration-of-the-aboriginal-women-of-val-dor

[3]The expression “shift disturbers” is credited to Lee Rose in Alexa Conradi’s book, Les angles morts, Perspectives sur le Québec actuel, Les Éditions du Remue-Menage (Québec, 2017), p. 12. http://www.editions-rm.ca/livres/les-angles-morts/

[4] Ibid, p. 31.

[5]Jackson Rising: The Struggle for Economic Democracy and Black Self-Determination in Jackson, Mississippi, by Ajamu Nangwaya and Kali Akuno (Daraja Press, October 2017). https://darajapress.com/catalog/jackson-rising-the-struggle-for-economic-democracy-and-self-determination-in-jackson-mississippi