Being Chinese in Canada: The Struggle for Identity, Redress and Belonging

by William Ging Wee Dere

Douglas & McIntyre, 2019 (400 pages)

A life of struggle for redress from Canada’s systemic racism

From 1885 to 1947, some 85,000 immigrants, mostly single young men, fled China beset by war, poverty, decaying feudalism and aggressive imperialism, for ‘Gold Mountain’ in Canada. Tales of the late 19th-century gold rushes in California and Canada had spread to the Guangdong province of Southern China where most of these men came from.

In the quarter century after Confederation, Canada, a European settler colony established on Indigenous land that the British had wrested from the French, had its own priority: to ‘nation-build’ a railway from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

And Canada wanted the Chinese ‘coolies’ to build the railway! “It’s simply a question of alternatives: either you must have this labour or you can’t have the railway,” Prime Minister John A. Macdonald told Parliament in 1882.

These workers lived in unsafe tents on dangerous terrain, while workers from the UK were housed in sleeping cars or railway-built houses, and many were killed by disease or in dynamite blasts. Considered hardy, industrious and frugal (living on fish and rice), they were paid less than even the Black and Indigenous workers.

Under Macdonald’s Chinese Immigration Act of 1885, to enter Canada they had to pay a $50 head tax, which was hiked to $100 in 1900 and to $500 in 1903, under Wilfrid Laurier. This head tax alone totalled some $23 million at the time (estimated at $1 billion a century later), while Canada’s total investment in building the railway was $25 million!

Worst of all, the Chinese workers were legally excluded from the burgeoning Canadian society and deprived of civil and citizenship rights, yet while also contributing to ‘nation-building.’ They were not allowed to bring their wives and families, but could go back to their native villages for a maximum of two years. They saved for the long trip, got married and had children, but came back alone.

The ultimate humiliation came on July 1, 1923, Confederation Day under Wilfrid Laurier, when Canada enacted a new ‘Chinese Immigration Act,’ which the mostly ‘married-bachelor’ Chinese community called the Exclusion Act: it banned Chinese immigration altogether! The Chinese protested to no avail, and named Confederation Day ‘Humiliation Day.’

The Exclusion Act was finally repealed in 1947, under Mackenzie King, after some 500 Chinese had been allowed to enlist in the Canadian Armed Forces to make up for the shortage of fighting men in the Second World War. With the newly declared United Nations Charter, the Chinese were finally given full citizenship rights – though they could bring over only their wives and children; it was not open immigration for them as it was for post-war Europe and even the Soviet bloc.

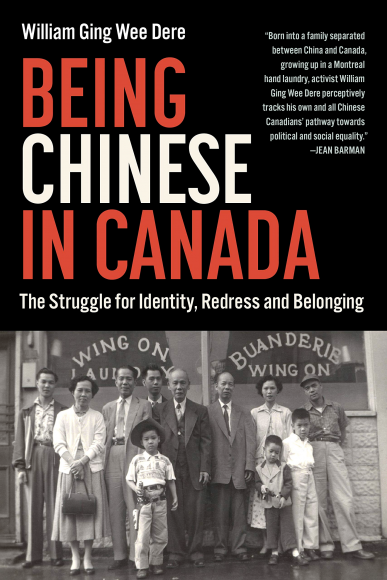

This is the core theme of William Ging Wee Dere’s impressive, combative, sensitive and patiently written semi-autobiographical 350-page book, Being Chinese in Canada, plus 40 pages of endnotes and an index of names, just published by Douglas and McIntyre. The book is illustrated with relevant old black and white photographs from the author’s album.

Schools, McGill and Marxist-Maoist political activism

William Ging Wee Dere was seven in 1956, when he arrived in Canada with his mother, Yee Dong Sing, who was then 50 and had brought up her five children in the family village of Fong Dang, Toishan County, in the South China province of Guangdong. A babe-in-arms, the youngest among five siblings when his father, Hing Dere, last visited China, he consciously met the latter for the first time at Montréal Central Station after the long train ride from Vancouver.

The book is very conveniently organized into four parts, and Part I is focused on his family. The author recounts his life in the back of the hand-laundry that his father, and his grandfather before him, ran with Confucian patience on Parthenais Street near Mont-Royal. He tells of Chinese life in Montréal in the first half of the 20th century, his discovery that his grandfather, Der Man, immigrated in 1909, and his father, Hing Dere, came over in 1921.

He discovered from the old men in Chinatown that his Ah Yeh, who died in 1966, was in fact a Confucian scholar. He also discovered later that his own father was a poet. After exposing him to the life rhythms in the laundry, even taking him on his rounds, and letting him adapt to Montréal, his father tried to enrol him in the neighbourhood French school; the school refused. An English school four blocks away, also Catholic, took him in. The only non-Catholic in his class, he learned the catechism and prepared for First Communion and Confirmation!

“In my parents’ traditional Chinese view of pleasing all the gods, to have another god to protect their son was a good thing,” he writes, adding that he became a fervent Catholic and even an altar boy at St Thomas More Catholic Church in Verdun!

William Ging Wee Dere grew up with solid Chinese roots and a strong sense of fairness, which led him to want to be ‘like everyone else’ and to be accepted as an equal citizen of Canada. The deep and lasting injustice done to him, his family and the Chinese in Canada remained a powerful driving force even as, and maybe because, he grew up during the Québec Quiet Revolution’s Maîtres chez Nous years and Pierre Trudeau’s Charter of Rights and multiculturalism policies.

After Loyola High School, he went to McGill to become an engineer. With that came the awakening of his political consciousness, which he explores in great detail in Part 2, with the authority of a rigorous note-taker. With Canada in 1970 recognizing the People’s Republic of China, Maoism met Confucianism for William Dere, who threw himself with dedicated gusto into the Marxist-Leninist movements that cropped up in 1970s Québec after the general strike in 1972, ending with the defeat of the ‘Yes’ camp in the 1980 referendum on sovereignty-association.

This section is a rich and informative foray into the Marxist Québec Left of the 1970s and 1980s. We get intimate insider views of Charles Gagnon’s En Lutte and of the Workers’ Communist Party (WCP) in which Dere was an activist. We encounter major figures from McGill, soft-spoken Indian revolutionary Daya Varma, who taught biochemistry, political scientist Sam Noumoff, and Prof Paul Lin, a personal friend of Zhou Enlai and a major architect of Canada-China rapprochement.

A decade later, many militants left and went back to mainstream society, like Gilles Duceppe who became head of the Bloc Québécois, Marc Laviolette who became head of the CNTU (better known as the CSN labour confederation), and Pierre Karl Peladeau who took over his father’s Quebecor empire and became MNA for the Parti Québécois. Founded in 1975, the WCP was dissolved in 1983.

Dere too quit the WCP, disappointed by the racism and sexism prevailing even among the Marxists! It had an all-white male top leadership, which dogmatically refused to link up with the Canadian black civil rights movement. Of the Indigenous peoples and their struggles, and of the rights of other immigrant communities, no mention was even made.

Struggle for equality and redress for Chinese Canadians

As William Dere quit Québec’s left politics, the creative tension between his humanism and his Confucian and Maoist Chinese roots threw him headlong into a quarter-century campaign to obtain redress for the 150 years of racist exclusion and humiliation inflicted on the Chinese community by Canada.

This protracted and tortuous struggle is exhaustively detailed in the seven chapters of Part 3. It starts with his direct involvement in Montréal and cross-Canada Chinese community politics and social work, spurred by a 1979 CTV broadcast on its then iconic W5 program, of a report titled “Campus Giveaway,” which accused Chinese students of ‘stealing’ university enrolments from (white Canadian) students.

He agitated to save Chinatown from municipal and corporate encroachments (which continue), fought school board elections and followed Chinese community leaders lobbying in vain for justice and recognition from federal politicians. Above all, he came up with the historic project to make a doc movie on the history and experience of the head tax and exclusion of Chinese immigrants in Canada. The low-budget film entitled Moving the Mountain, made in partnership with his former WCP comrade Malcolm Guy, premiered in 1993 at the Toronto International Film Festival. But it never aired on CBC, where Mark Starowicz, Loyola alumnus and former editor of the McGill Daily, was boss of documentaries.

Still, the movie pushed the Chinese redress campaign forward, from consciousness-raising to consensus-building and mobilization. Unexpected help came from Ronald Reagan of all people: in 1987, he offered $20,000 to Japanese-Americans who had been interned during WWII. Brian Mulroney followed suit in 1988 by offering $21,000 to each interned Japanese-Canadian and their descendants.

But Chinese lobbying of Canadian ministers and politicians failed, with Chinese national and regional organizations jockeying for influence and government funding. On the eve of leaving office in 1993, Mulroney offered the head tax and exclusion victims a gold medal and a certificate of honour – an offer the community rejected as “ignominious.” But the mainstream media had finally begun to report and editorialize seriously on the head tax redress issue.

Chrétien’s three-term government (1993-2003) appointed Hong Kong-born Adrienne Clarkson as Governor-General, and her sister Vivienne Poy as senator, but refused all talk or compromise on the head tax issue. This episode is detailed in Chapter 14, “Closing the Floodgates,” in reference to bureaucrats who were determined to dam the ‘floodgates’ of compensation opened by Mulroney’s concession to the Japanese.

The redress movement internationalized its campaign and received support from UN Special Rapporteurs on human rights, who reiterated, but in vain, recommendations for Canada to rectify the damages of the Head Tax and Exclusion Acts.

The redress campaign took the matter to court – and lost, with further humiliation when Ontario Appeal Court judge James Macpherson ruled, with heavy racist stereotyping: “The Chinese head tax payers were happy to be here and had already received redress through their ability to remain in Canada… Paying the head tax is made all worthwhile when one can see their granddaughter playing first string cello for the Toronto Symphony Orchestra.”

Paul Martin stuck to Chrétien’s ‘No negotiation, no compensation’ policy, and it took the January 2006 defeat of his Liberals by Stephen Harper’s Conservatives to break the redress logjam. Bloc Québécois candidate May Chiu, a lawyer, Chinese community activist and close associate of William Dere, brought down Martin’s own vote in Lasalle-Émard from 36% to 30%!

But when redress came, it was half-baked. On June 22, 2006, Harper offered an official apology in Parliament, in Cantonese: ‘Ga Na Da Do Heep’ – Canada apologizes. Symbolic payments of $20,000 were made to 785 head tax survivors and surviving widows, for a total of $15.7 million. But nothing was provided for their descendants, some of whom were elderly and had also suffered and shared in their parents’ humiliation.

Personal life, wistful humour, reflections on the future

William Ging Wee Dere’s book is packed with previously unpublished information and peopled with mostly unknown names; it takes us into little-known milieus and often hits us with unsuspected insights. But his writing style, swinging from matter of fact reporting to lyrical reflections, and his often self-deprecating, wry humour, lighten the reader’s mood by providing comic relief in the thick of a long epic struggle.

His marriage to Gillian Taylor, a WCP comrade, their family life with two children and subsequent divorce; his friendship and affair with GG, a Chinese Malaysian student who had a crush on him since his McGill days; and his courting of 28-year-old Dong Qing in Shaoguan, Guangdong Province in 1990, with her family, in the festive atmosphere of the Chinese New Year (the Year of the Horse), their marriage (William was 41), and their settling “happily into a somewhat unorthodox middle-class life in Canada” make for beautiful reading in their own right.

“Being Chinese in Quebec” is the title of Chapter 17, the first of three chapters in the final Part 4 of the book. It focuses on William’s disagreements with his old comrade Malcolm Guy who co-directed Moving the Mountain, over a new film project, Being Chinese in Quebec: A Road Movie.

William left the project as his proposals to show the victorious anti-racist struggle of 15 ‘new immigrant’ Chinese workers at the Montréal Calego Inc. backpack factory, the ‘slanted eyes’ racist comment of Parti Québécois leader André Boisclair, the Chinese immigrants’ contribution to the wealth of Lord Mount Stephen (the rice baron who built the ‘Jardins de Métis’ Reford Gardens near Matane on the South Shore of the Lower St. Lawrence river), and the Christian proselytizing carried out by a Chinese evangelical couple from Hong Kong inside the Aboriginal Cree community of Ouje-Bougoumou in Northern Québec, were either dropped from the script or later cut before airing.

In conclusion, let it be said that William Ging Wee Dere’s book itself reads like a superb film script. And it stands out as a major decolonial anatomy of English/French settler hegemony in Canada. Any takers?