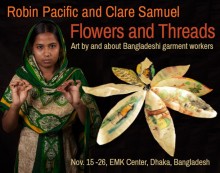

Shapla on grass – 220×165

Robin Pacific is a Toronto-based artist who has just completed a project with garment workers in Canada and Bangladesh. In the capital city of Dhaka, she met women who had migrated from their village homes to find employment in the city’s garment factories. Nilambri Ghai from Montréal Serai had the opportunity to speak with Robin.

Serai: Tell me about your project and your interaction with garment workers.

Robin: There has been a phenomenal social transformation in Bangladesh, where there are now about 5,000 factories and four million garment workers, 85 percent of them women. Most of them have come from small villages because of the need to work and to escape the poverty that is so dire in the countryside. It’s been a double-edged sword because on the one hand, it’s taken women out of cultures where they are oppressed (if that’s what one can say) into a situation where, in spite of the sweatshop conditions, and the inhuman ways in which they are treated in the workplace, they have a measure of social independence. They have a social network of other women their age, and that is quite liberating. I had conversations with 36 women. I can tell that they are homesick. They feel in some ways alienated from their own culture. It is a complex, changing set of social phenomena. This has been both good and bad. Some of the women have avoided child marriage, others have come with their families. Often, when the husband can’t find work, the woman ends up being the sole breadwinner, which is sometimes resented by the husband, and occasionally results in domestic violence. But for many, the move has provided tremendous autonomy and freedom.

Serai: Who takes care of the children?

Robin: That’s a good question. I wasn’t always sure – sometimes it’s a neighbour, sometimes a relative. Some of the children go to school during the day, and when they return, they are on their own. The other thing is that the women are able to send their children to school and, without exception, all want their children to go to school and to become professionals. The women like their work and are proud of it, but they don’t want their children to be garment workers.

Serai: What about housing?

Robin: They are living in substandard housing, and every time the minimum wage goes up – as it has done twice in the last few years – the rents and the cost of food go up, but they have enough to send a little bit home, to send their kids to school, and to basically feed the family. They are often laid off if the orders are slow, and pretty typically anyone trying to organize a union is fired. All the women that I spoke with are in trade unions and are represented by two major labour advocacy groups: Solidarity Centre/Bangladesh and the Bangladesh Centre for Workers’ Solidarity. Solidarity Centre is funded by the AFL-CIO. Its executive director is Alonzo Suson, and I have worked very closely with him. Kalpona Akter is the director of the Bangladesh Centre for Workers’ Solidarity. She is a very well-known activist who has spoken many times in North America.

These two groups promote union activities. They train workers to become leaders, and they organize labour groups in the plants and garment factories. Most unions in Bangladesh are corrupt, and are financed by – and support – political candidates. At times they are allied with neighbourhood mafia-type groups. But these two groups and the unions they work with are independent. The women I spoke with are trade unionists. Quotes from them are available on my website: http://www.robinpacific.ca/projects/flowers-and-threads-exhibition-in-dhaka/

Serai: You also spoke with garment workers in Canada. What struck you most about people from two very different environments? What was it that most impressed you?

Robin: It was interesting in that, again, in Canada, the garment workers liked their jobs and took pride in their work. We tend to think of these women both here and in Bangladesh as being miserable, or downtrodden workers. But they take tremendous pride in their work, and that is something that I found to be very interesting and inspiring. Garment workers that I spoke with here all belong to Workers United Union – an organization that has done a lot of work around Bangladesh as well. The garment workers here were making minimum wage, which is $11.25. Many of them have been working there for years. There have been so many layoffs that only those with the most seniority have managed to stay on. Some of them have worked for 15 to 30 years at the same place. I took a tour of the Coppley Suits factory in Hamilton and saw that most of the machines were lying idle. That is what happened to the manufacturing sector with globalization, and as a result of the free trade agreements of the 80s and 90s. The other point I noticed was that they all wanted their children to get an education so that they do not end up as garment workers. I asked people similar questions both here and in Bangladesh: What is the first thing you see in the morning? What are your hopes? Where do you find your strength? Most replied that they wanted education for their children, and that they got their strength from their network of families and friends and from their unions.

I asked them to make drawings on petals. The sessions in Bangladesh were facilitated by Leah Houston who led the petal-making workshop, while I worked on the conversations because I needed an interpreter. And all throughout, Clare Samuel made these beautiful photographic portraits of garment workers in both countries. They made 18-inch panels on Japanese paper with watercolour crayons, and I assembled them into Shaplas (water lilies) – the national flower of Bangladesh – and we hung these from the ceiling at the exhibition in Dhaka. Each one had four petals: four made in Bangladesh, and four made here. It was a physical manifestation of solidarity. The project is really about building relationships across language, culture, geography, religion and race.

I did a performance in a subway here with a Bengali poet, and it was contextualized around asking questions such as: Do I have the right to represent these women? Whose voice are you hearing when I read their words – their voice or mine? Is my aging white body a bridge? Am I appropriating their voice or am I facilitating it? I’ve asked these questions throughout the project. It was really important for me to keep raising these questions.

Serai: I find it very unusual and interesting, especially the way you bring out these questions. Did you get any answers?

Robin: I don’t think there are answers. I feel that I need to keep questioning myself as a privileged white artist, and addressing my unconscious assumptions. For example, I might believe that having a Canadian passport would keep me safe, but in fact, it could make me a target, thanks to the Canadian presence in Syria.[1] Also, I might feel that being an artist would give me a free pass. Well, being an artist does not give you much credibility with ISIS, which was laying claim to killing foreigners in Dhaka.

Here I was, a seventy-year old Canadian artist, and yet I found the garment workers in Bangladesh eager to participate and to be part of something. We told them that we were there because we wanted to meet the women who made our clothes, and I think they were very appreciative. These issues are very complex and yet you don’t want to question yourself into a state of paralysis.

Serai: And yet at one level, they are very simple since they involve interacting as one human being with another. It depends a lot upon the individual, and you were able to connect and reach out.

Robin: I’ve been trained in listening skills, and when I was talking to women, I was simply being attentive and listening to their reality. It was beautiful, extremely moving, inspiring. They gave me more than what I gave to them. It was a wonderful experience. When I went back the second year and set up the exhibition, fifty of the garment workers came to the reception, and when they saw their drawings, their photographs, their words on the wall, they were so full of joy, it was one of the best experiences I’ve ever had.

Serai: Did you have sponsors for this project?

Robin: We financed the first trip ourselves. The second time around, a friend of mine held a fundraiser and raised $10,000.

Serai: Tell me a little about the Lit Fest.

Robin: I had heard about it before I went and thought it would be a nice way to relax after the show, and then all this security stuff happened. The poet who had performed with me in the subway was writing for one of the secularist blogs, and her name and mine were all over the Internet because we had publicized the show. Five of the writers on that blog had been set upon and hacked to death by fundamentalists with machetes. I was really scared before I went, but I did go. But when I went to the Lit fest, it was amazing to hear all those writers, many of whom face tremendous threats, and to see that they were not allowing that to silence them. I found that I had gained a tremendous amount of strength from this knowledge, and in a small way had earned the right to be there. I saw that there were people there who were much braver than I was. It was a great privilege to meet some of them, to talk to them, to hear them read and speak.

This was their fifth Lit Fest. There is a Dhaka Art Summit that comes up every February. The Canadian High Commissioner in Bangladesh has invited me to go back and do another art project with workers. Dhaka is a really incredible place, a very difficult place to be because the traffic is so insane, and given the density of the country’s population – there are 170 million people in an area one-sixth the size of Ontario. The density in Dhaka is a crazy figure, like 19,000 people per square kilometre. And yet it is so alive and interesting. There certainly weren’t many tourists around except for one or two.

Serai: Not even in the city?

Robin: No foreigners went out there. The expats were on lockdown because two foreigners had been killed and ISIS had claimed responsibility. The Canadian and US embassies were locked down and people could only go to and from work. All the retailers who send their buyers for Christmas orders cancelled their trips. Everyone was on high security alert. Nobody was going there. The tour company that I worked with and from where I met Zia Uddin Ahmad, a wonderful interpreter who collaborated with me on this project – that company had to lay off many of their tour guides. Whoever was responsible for these killings did a lot of damage to the economy of the country. Some people believe that these were politically motivated. The current prime minister has been trying war criminals from the 1971 War of Independence. Zia said to me one day: “You know, Robin, you’ve been working very hard – you should go to the country for the weekend. I’ll take you to this village – you will love it – we will stay in this ecological rest house and you will be able to see the weaving of jacquard sarees.” We had a police escort back to Dhaka. It was only when we got back that I figured out that he had wanted me out of the way of potential riots in Dhaka following the hangings.

Can I talk about my labour campaign? All these projects are leaning toward a consumer awareness and activist campaign I am planning. Every time I talk to people, they express their resentment against big companies employing workers in Bangladesh. They want to know if they should stop shopping at Joe Fresh, H&M, and so on. The garment workers, however, don’t want a boycott. They want the orders, and want to keep their jobs. This made me develop my FAST campaign. It stands for FAIR living wage; ADULT labour only; SAFE working conditions, and TIMELY pay for work and overtime. What the campaign will include is a label shaped like a little t-shirt with a website address and the acronym: FAST. You will be able to pin the label onto your clothes, like an elaborate political button. On the website, visitors will learn that for a small increase of 2 percent on clothes, the FAST conditions could be met. The website will direct visitors to write to major retailers indicating their willingness to pay that 2% more so that garment workers can have a decent wage and working conditions.

Serai: What are the conditions like? Have there been any improvements?

Robin: The factories are not safe. There was a big scandal with the company H&M, which claims that factories are now safe, but these companies do not even know which factories are making their products in Bangladesh. The pressure is now there for supply chain transparency to allow people to know where their clothes are being made. Garment factories don’t want to pay what it takes to make the factories safe and to pay for worker training on safety features. Also, over 800 people have died in factory fires because they don’t allow women to take bathroom breaks, or because they think they will steal (so they lock them in).

Serai: So what do the women do when they have to go?

Robin: I guess they schedule breaks. I know, it’s incredible the kind of control and exploitation of women’s bodies that we see over there. I often ask them if unions have made a difference. Although there are 700 unionized factories, there is not even one collective agreement. However, the women tell me that whereas earlier, supervisors would spit on them, swear at them, hit them, and yell at them and deny them bathroom breaks, once a local is certified in a factory, the spitting, hitting, swearing and yelling stop. In my opinion, unionization is the only answer, and we can contribute to making this possible by agreeing to pay that extra 2 percent. I plan to roll out my campaign within the next 12 to 18 months.

Serai: Robin, thank you very much for sharing this. Best wishes to you for your upcoming campaign and current projects.

[1] Editorial note: Canada’s greater military presence in Afghanistan is worth noting here as well.