Jeff Barnaby was born on a Mi’gmaq reserve in Listujug, Quebec. He has worked as an artist, poet, author and filmmaker who was recently nominated at the Genie awards for best short film – File Under Miscellaneous (2010). His work paints a stark and scathing portrait of post-colonial aboriginal life and culture. His previous films include From Cherry English (04) and The Colony (07). Jeff is currently in development on two feature films, Blood Quantum & Rhymes for Young Ghouls.

Q1: What inspired you most to become a director? Was it always a life-long passion?

Absolutely not, I always wanted to work in some sort of creative discipline for sure, but growing up on a reserve I didn’t even really know that was a viable option. It was more or less carpenter, fisherman lumberjack, something blue collar, feed your family, keep a roof over your head… I remember telling a guidance counselor at a young age that I wanted to be a writer but even then, I think, it was just to shut him up. When I was growing up, college and university was just starting to become feasible – something that little Indians could actually explore and get something out of. I drew and wrote a lot as a kid and I never thought that it would ever turn into anything legitimate.

It really wasn’t until I went that post-secondary route and attended Dawson that I started becoming interested in film, as an academic pursuit, rather than just pure entertainment. It was the professors there that really opened me up to how much I had an aptitude for it, and how well all the skills I had mustered up until that point translated into the filmmaking, which is basically an amalgam of other artistic disciplines anyway. I already had a pretty honed visual sense by the time I got there. Film to me was just another way of expressing it, which at the end of the day is what really interested me. But I wasn’t reenacting scenes from Star Wars with a super 8 camera in my back yard or anything like that, cinematography was new and exciting, and gave me a platform to do all the things that I had been doing up until that point on top of things that I’ve never done before. To this day, I think it’s what actually keeps me loyal. Love it or hate it, there are no ‘boregasms’ in filmmaking.

Q2: How would you define your artistic style?

If it were to be in a single phrase it would be ‘eclectic saturation’. I try not to weigh myself down with any particular approach, i.e. just watching movies, or reading comics or even focus on art in general. I think any good commentary, which is basically what good art is, comes from experience – getting your hands dirty. I’d like to think my movies, poetry, and drawings, whatever, are basically hyperbolic interpretations of things that I’ve gone through or seen firsthand. And again, just coming from a variety of artistic backgrounds those experiences go through a myriad of filters before they find themselves on a page or a screen, sometimes to the point where I don’t necessarily recognize myself in what I’m doing. I also like to engulf myself in the technical process of whatever it is I’m doing at the time, I think part of the discipline of being a good artist is getting to know your craft, know how to load a camera, how to adjust a light, how to draw a storyboard, how to take a basket case actor out off their trailer using only a cucumber sandwich.

There’s this great quote from Tsunetomo Yamamoto, the man who wrote the book of the samurai: “a person who is said to be proficient at the arts is like a fool. Because of his foolishness in concerning himself with just one thing, he thinks of nothing else and thus becomes proficient. He is a worthless person.” I approach my life, and my work with that spirit. That way given the chaos you find on any given set: an escaped giant cockroach, someone shooting up, a chainsaw that might accidentally kill your lead actor, you take it all in stride and dare I say welcome it.

Q3: Funding agencies in Canada often fall into a pattern of promoting what you refer to as “feather and drum” stories with respect to aboriginal film-makers and artists. How would you describe the present state of aboriginal film in Canada?

I really don’t know how to answer that because, a) that answer is pretty much a novel, and b) as of late I’ve been slowly withdrawing from that particular scene and I really wasn’t 100 percent a part of it anyway. Being in Montreal I feel like I’m more of a part of the film and art scene here then I am part of any native scene, despite the language barrier or maybe even because of it. At any rate, I’ve been turned from every major aboriginal envelope in continental North America, and some of the things these organizations have said to me have been pretty ugly. The majority of my funding comes from Le Sodec who are more interested in making good films then they are in representing any particular kind of ideology, which is what makes them so off-the-charts awesome to me. When everyone else rejected the first draft of the colony, they stuck by me and told me, specifically told me, NOT to tone it down. I’m interested in being uninhibited, imaginative, thoughtful and evocative in the things that I do and put out there; otherwise what the fuck is the point? A lot of these organisms are more interested in righting the wrongs that a century of cinematic misrepresentation has wrought more than they are making good provocative films. And I can totally understand that approach, but I think the people that are running these organizations and festivals need to understand that what they are doing is censorship and undermining the whole purpose of promoting native cinema in the first place and that’s to give voice to a marginalized section of our culture not to make propaganda movies of positivity.

Despite having one of the highest suicide rates and aids rates and murder rates in any developed nation on the planet, you actually never see that represented in main stream native cinema. I remember I had a First Nations in film class when I was at Concordia, and one of the questions our professor asked us was, is there such a thing as a positive stereotype. To which I kind of jokingly replied: “yeah, that Indians have big dicks.” I couldn’t help it. Haha, anyway, after I thought about it bit more the answer was invariable no, no there isn’t, because either way you’re still totally misinforming, so where you have little Mi’gMaq kids wanting to be John Wayne, you have little Mi’gMaq kids wearing head dresses instead of taking an interest in their own culture.

So, Indians in film went from dog-eating pedophile cannibals to tree hugging shamans holding crystals up to the fucking moon. And the film industry has never really let go of that white guilt stereotype of Indians. And you see it manifest itself over and over again, you get movies like Pathfinder, Dances with Wolves, you get movies like Pocahontas (there’s no way an Indian would have an ass that big) and the latest cluster-fuck, Avatar. I think one of the things that I’m trying to do in my films is get rid of that imagery and humanize, flaws and all, Mi’gMaq men and women, and I say that specifically, Mi’gMaq, I am Mi’gMaq filmmaker not a native one, because by far one of the worst by-products of that drum-and-feather stereotype is pan-Indianism. You know, even if shamans could make fire flies dance around and talk to trees and shit, I would still rather share a beer with that carpenter, or the lumberjack, or the fishermen, if only because they have better stories to tell.

Q4: In your short film The Colony, there is a magnificent scene where one of the two main characters, Maytag (played by Glen Gould), sits drinking beer and describes how it was like growing up and reading comics where the bubble dialogue of the animated characters was being translated into Mi’gMaq – cinematographically, the comic and the graffiti merge very well creating a dark mood of being frozen in childhood which permeates and enhances the film. Can you tell us about a bit about what it was like growing up and how that influenced your storytelling?

My growing up is Listuguj, simply put is my storytelling. The way people talk, the way they interacted, the dark humor, the characters, right down to the specific words they use – and how they use them. Listuguj needs a fucking reality show. It’s not only that either, the pride that they have in the culture and the Mi’gMaq language itself was just starting to revive, actually when I grew up there they were still calling it by its English name, Restigouche, you see the film Alanis Obomsawin made during the early 80’s in was incident at Restigouche not Listuguj, so that from a very early age that sense of pride was instilled in me. And growing up around the time that movie happened also instilled this sense of confrontation in me and self-worth in me, that indeed being Mi’gMaq was something to fight for, to bleed for, to die for. I did a doc on the Mi’gMaq language for a television show called Finding Our Talk, and the I interviewed this old timer that had left to go work in Maine because there was really no work in community at the time, and as he got older and ended up coming back home and one of the last things he said in the interview, which was predominantly in Mi’gMaq was “I’ll die here.” No matter where I lay my head between now and the day they dig my hole, that hole is going to be in Listuguj. That is the place that built me.

Q5: What do the cockroaches represent in The Colony?

Well I guess that really depends on the viewer I guess, for me they represented a whole whack of things, I wanted to put allusions in there to both naked lunch and Kafka’s seminal novella the metamorphosis, and use the symbolism from both of those books to reinforce the main character’s alienation from society – his loneliness. The only thing keeping him company there are the bugs. Reinforce this idea of the grungy urban dirtiness also. For some reason I only associate cockroaches with the city, although I’ve never actually seen one in the 12 years that I’ve lived here.

I also wanted to make a movie about the after math of some of the history of first nations people in Canada, which is one of the things that we do share in common, that same background, but I didn’t want to do it in a preachy romantic kind of way where there were any “once we we’re warrior” speeches at the end. I wanted to have shit blow up and there not be any happy fixes at the end. So, I needed something to represent this post-colonial indifference effectively displayed by non-natives and not have it be the clichéd villainous white man – so what better device to use then the insect. I’m reminded of Seth Brundel speech from the fly: “Have you ever heard of insect politics? Neither have I. Insects don’t have politics. They’re very brutal. No compassion, no compromise. We can’t trust the insect.” Even taking that out of context it applies to the relationship between natives and non-natives. The native scene needed a film like that, a film that very bluntly stated, albeit through symbiotics, that there was indeed an aftermath, and that it was inhuman, and that the ignorance was very literally killing us. I think a lot of people think that since there are no small pox out breaks anymore and that all the residential schools shut down Indians should stop whining and open a casino or start selling cigarettes. At the end of just breaks my heart and makes me rage, because you just feel so helpless to stop any of it.

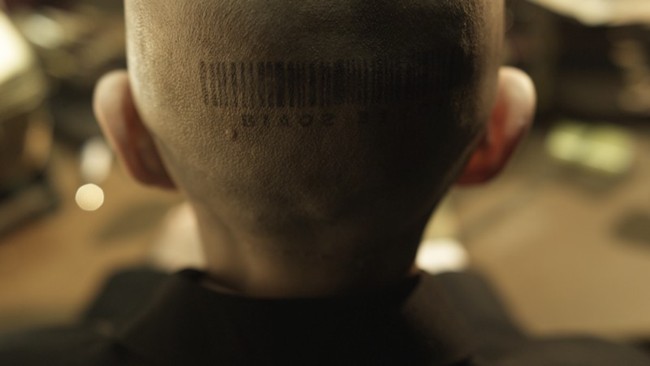

Q6: Tell us about your other short film – FILE UNDER MISCELLANEOUS – it’s a surreal story that features a very deep-rooted identity crisis. How would you describe this film?

I had come up with the poem that the film was based on quite a while ago, during my first year of university at Concordia. I was in a poetry class with a bunch of hipster douche bags and there was a serious disconnect going on within the class that spoke to a larger problem of my just not feeling like I belonged anywhere in particular, something that I have to say that still happens when I’m at festivals or other events where I’m the only reserve Indian within miles, and I’m not one to project sycophantic arty douch baggery circle jerk look how clever we are either, so needless to say I flat out do not fit into to any of these scenes to well. So rather than don a poor me attitude and self-destruct, I poured all that grief into this hollow point bullet of a poem, and it was based on these conversations I had with friends of mine who would say things like “I wish I was white.” And the more I talked about it the more I realized how much of a common sentiment that was.

On a public platform you’ll hear a lot native pride, on a private one you’ll hear a lot of self-loathing, which I think is symptomatic of what I was talking about earlier, post-colonial aftermath, Indians were taught to hate themselves, we didn’t just wakeup doing it one day. And it was the same approach I take to all my films, present and execute the concept in an original way that was both conceptually and aesthetically challenging, which to me meant doing a Sci Fi film. Plus no one has ever really done that before; to me, it just made sense to put this Indian in a hell raiser/blade runner type atmosphere in a unspecified timeline in the future where skin replacement was not only a viable option it was the only option viable for individuals that felt dehumanized and wanted to feel connected to something. It’s a sensitive subject in a climate where multi-culturalism is promoted as a positive thing and I don’t necessarily think that’s the case with native people. Be it if you’re Muslim or French or Spanish or Mexican or Greek, there are whole countries that share that culture and if you’re getting lost in the diversity of a large populace of a Toronto or a Montreal you can always go back and touch base with the progenitors and relearn the intricacies of that society again. But what if you don’t have that base anymore? Then you will get lost. I mean it’s not a stretch to say that young native people are more enthralled by pop-culture then they are their language teachers. And if you go back to this idea of promoting pan-Indianism as an accurate representation of all native cultures then you have individuals with no real touch stones to who they are, hanging dream catchers from their rear view mirrors, or wearing Washington redskin apparel to express their identity. I genuinely believe that as horrific as the world is in FUM – it’s where we’re heading if this attitude continues.

Q7: What are your future production plans?

Well the idea was to do a zombie movie, a little piece of trivia for the film buffs out there, the CGI blood you see in the colony at the end is actually leftover blood from the dawn of the dead remake. So I wrote this script called blood quantum, which of course makes reference to the practice of measuring the degree of ancestry of for the individual of a specific racial or ethnic group, this was put into practice to define who was or wasn’t native as far back as the 1700’s. So the idea would be that these immune Indians on this fictional island reserve called red crow of course based on my home community of Listuguj, are faced with the horrific idea that any non native person on the reserve can – at any minute – turn into a homicidal flesh eating cannibal. Haha – it should get funded on that statement alone. And so goes the question of do we excommunicate these potential zombies or help them.

Though the time is right, given the interest in both zombie pop culture and sexy leading native protagonists, I just don’t think I’m right. So my producer, John and I, decided to do something a little less EFX laden, even though all our films thus far have been crammed with EFX and we have one of the best CGI appliance EFX teams a filmmaker can ask for, I think we need to build up our stamina for what would be realistically a 40 plus day shoot. So, I started writing another feature called Rhymes for Young Ghouls, about a young Mi’gMaq girl wrapped up in her family’s drug trade dealing with the death of her mother and father’s imminent release from jail. I’m really starting to get into that now, it’s starting to get a face. It’s not blood quantum, but I’m starting to feel it.

Hopefully if all goes well, we can shoot that sometime this year. Some of my own personal projects involve a book of short stories and poems that I’ve been working on, I’m starting to bone up on my illustration skills again, trying to integrate Photoshop, and Illustrator into my skill set, trying to ink on tablets rather than the more traditional methods, and writing and drawing are still my first loves. Setting some music down in something other than my films would be nice also. I have a lifetime to chase rainbows.

Q8: What would you like people to know most about you or your work?

Authenticity and fearlessness, at the end of the day I want to represent. I want to be honest. I want people to know the places I take them are genuine, not a romanticized version of an ideology that never existed.

If you are interested in seeing some of Jeff’s works please click on one of these links:

http://www.eyesteelfilm.com/thecolony

http://www.nativelynx.qc.ca/en/cineastes/barnaby.html

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i-nRFpkrvKY