Film Review of Mathieu Roy’s The Dispossessed (Les dépossédés)

The camera shows a woman in a field. The ground around her is rough, with a bit of greenery in the distance. She goes down into a ditch, comes up with her shallow enamel bowl filled with water and tilts it into a watering can. In this way, she fills the whole can then takes it a bit further out into the field and waters the parched ground. Though the ditch with its muddy water isn’t shown, we can imagine it and we realize that this is a precious resource for her.

The camera stands still – an observer, interested but unobtrusive. There are no zooms, no close-ups, no cinematic gimmicks that viewers have become so accustomed to.

This opening shot from Mathieu Roy’s The Dispossessed (Les dépossédés) encapsulates all that is to follow. This is the life of a small farmer in a so-called developing country – an existence replete with repetitive, continuous physical labour that goes unnoticed in the high-tech frenzy of urban existence.

The small farmers in Roy’s film are ever-present in our world, have been for time immemorial, with their basic tools, humble dwellings and simple diet, and they are numerous, 3.5 billion to be precise. And yet they are almost invisible. Roy’s intention in The Dispossessed is to imprint their hardy existence on our consciousness.

The film brings to mind the magnificent photographs of Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado in his book entitled Workers. Here he powerfully portrays, in stark black and white, labourers of all ilk from across the world, documenting and dignifying this million-armed surge of humanity. Roy’s ambition goes beyond bearing witness. Aided by his talented cinematographer, Benoît Aquin, he poses the question: why are these feeders of the world so marginalized themselves and often so malnourished?

That question becomes a piercing arrow in this political film, which goes from micro to macro settings, often from one frame to the next. Given the palpable reality of peasant life that it embodies, a bird’s eye view of a giant fallen tree and women hacking away at it with an axe to make firewood; a misty shot of two young farmers seeding and spraying their fields; the slick precincts of the World Trade Organization (WTO) or the high-tech lab of Syngenta, the world’s largest crop chemical producer with approximately US$13.4 billion in 2015 (source: Wikipedia), come as a visceral shock.

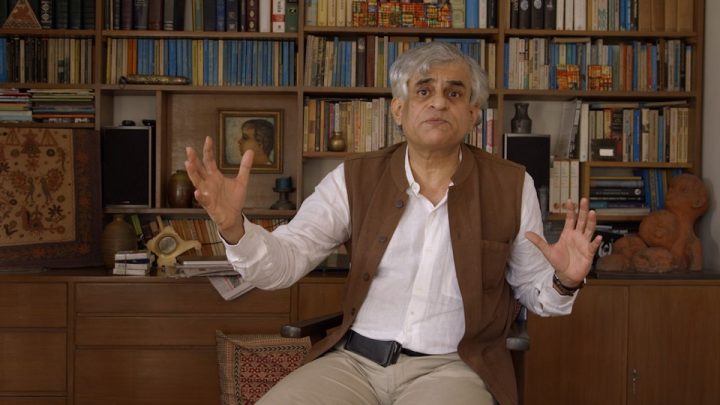

Worldviews collide, particularly when Roy interviews a left-wing Indian economist and award-winning developmental journalist, P. Sainath (Everybody Loves A Good Drought, 1996, Penguin India), who, along with others, delves into the whys and hows of farmer disempowerment – western protectionism of agriculture and the dumping of cheap surplus grain and other foodstuff in developing nations; farmers forced to shift from food to commercial crops that are priced by a volatile commodities market, wreaking havoc for small farmers; the need to take loans to buy expensive and harmful chemical inputs that have caused massive indebtedness in India and a wave of farmer suicides; not to mention the degradation of soil fertility and other environmental fallouts of neoliberal policies.

In underlining the global scope of the problem, Roy takes us to Switzerland where traditional dairy farmers in a remote, rural community talk about their inability to compete with a market flooded with commercial, factory-produced milk – an ethos that treats cows as milk-producing units, making profane the age-old bond between a farmer and his or her animals.

For me the success of this 3-hour film rests in the indelible images of the unending work of farmers and people in farm-related sectors, and the way the film weaves together the human and political story (micro-macro) into a cogent and compelling whole.

“These (small) farmers are inefficient; they should be doing industrial jobs; let global agribusiness feed the millions,” is a common cry of market-is-king economics. Roy’s rejoinder to this is to show the displaced rural poor, working on a huge construction site in an Indian city, with no safety equipment, babies tied to the women labourers’ backs or older children walking around on slabs of concrete hundreds of feet above the ground. The camera shows a crumpled sheet on the slab and a woman bathing with water gushing out of a pipe in far shot, letting us know that for these people, even the basic brick structure that we were shown as their home in their village is now gone.

My only critique of the film is that the approach of ‘show not tell’ and ‘letting the camera sit still as action unrolls before it’ (that is so life-like and effective in depicting the farmers’ lives) does not work when the camera is trained through a window on executives dining in expensive suits or on a blonde woman relaxing on the roof of the WTO, taking her sunglasses on and off and talking on her cell phone. The camera, humane until then and intelligently probing, grows petty and didactic, falling short of the systemic critique that the film otherwise makes so well.

The last scene is also a telling one. Now the farmer has somehow procured some grain and is shown squatting near a mud hearth at dusk, cooking cereal in a pot that she balances with some difficulty over her faulty “stove.” She stirs her proverbial pot, and we realize how very little she has to eat and how precarious is her existence.

These images in the film will stay with you long after you’ve exited the theatre and the statistics and arguments have faded. The conviction will remain with you that a terrible wrong is being inflicted here – one that must be exposed, fought against and righted.