Introduction

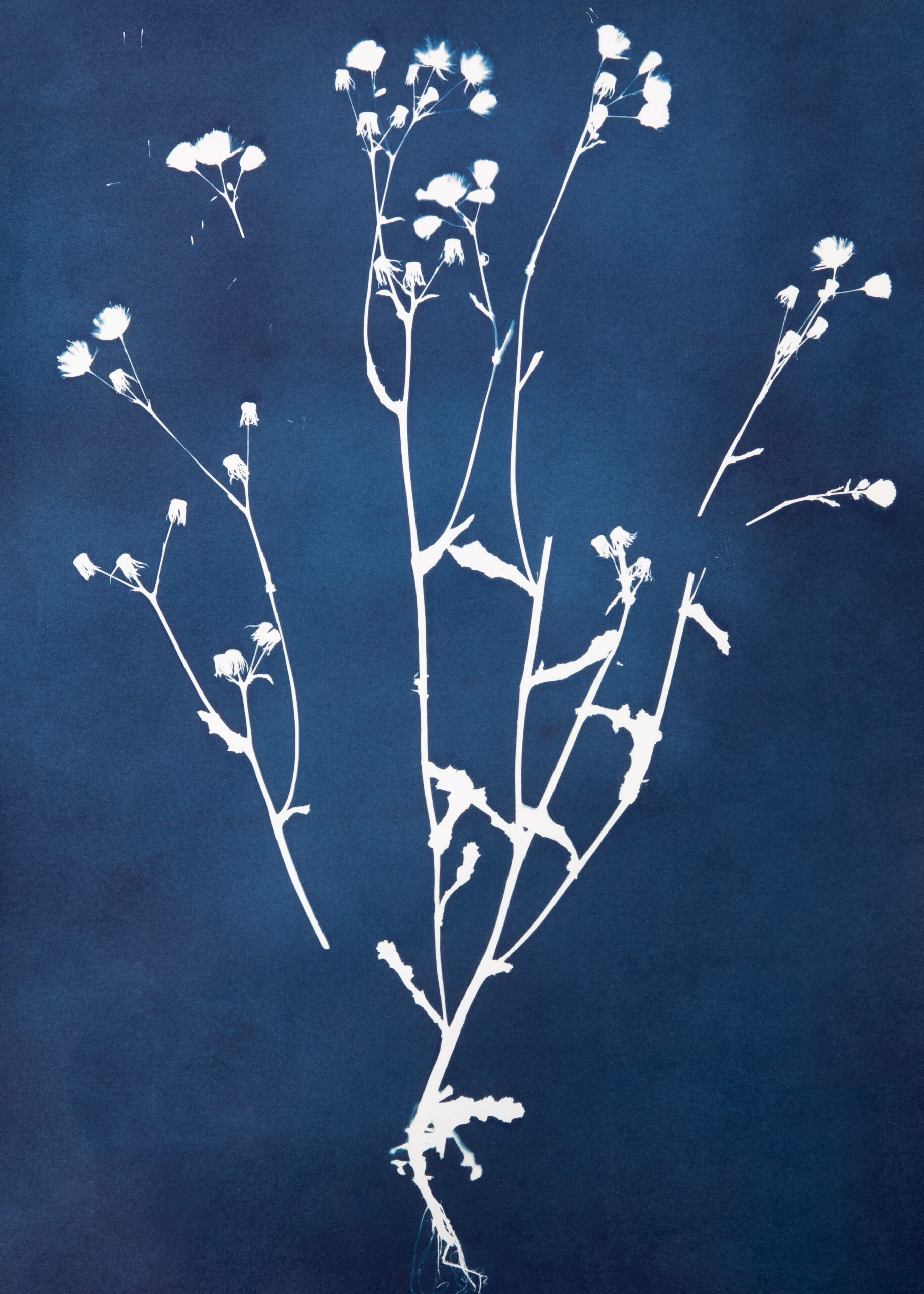

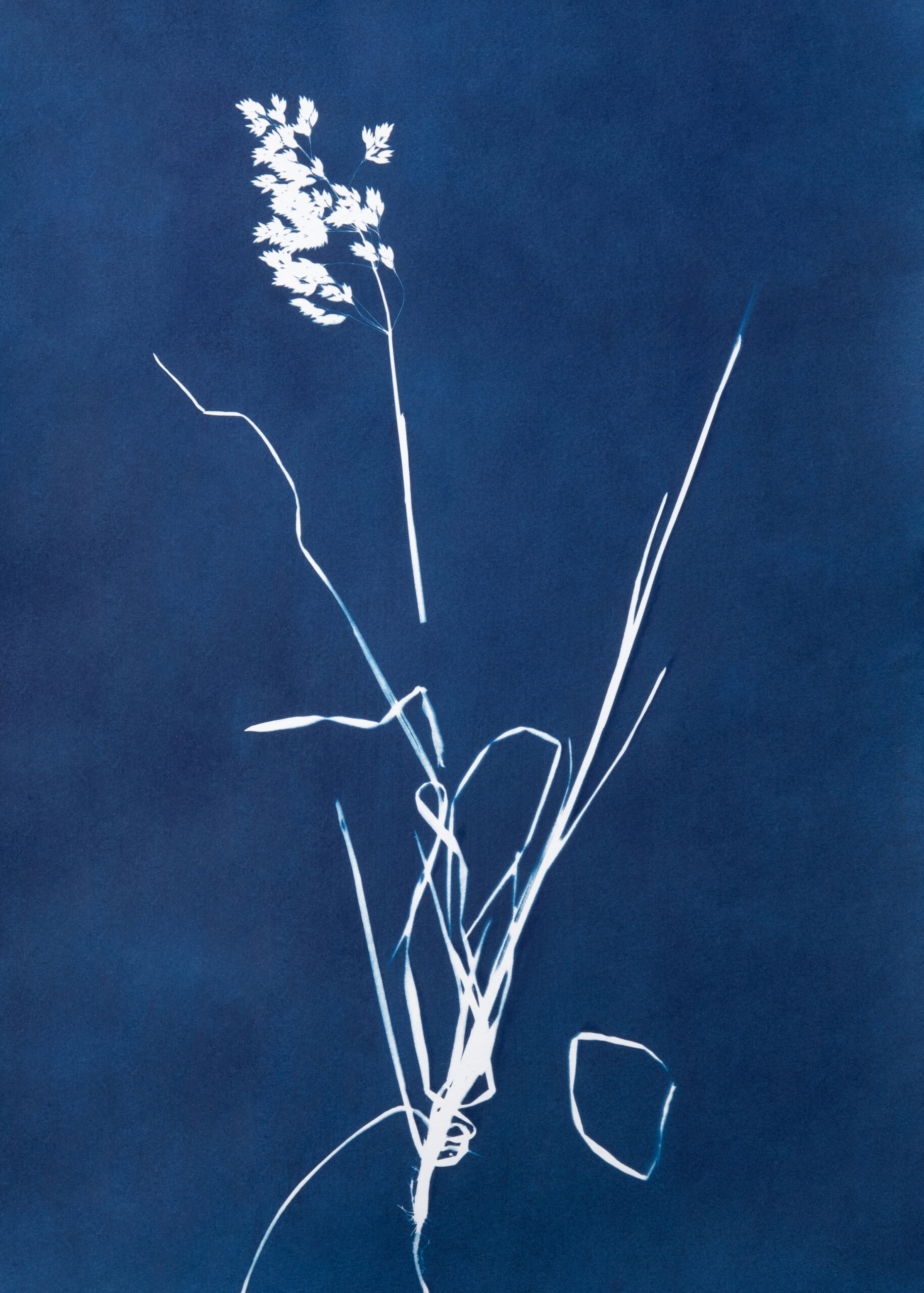

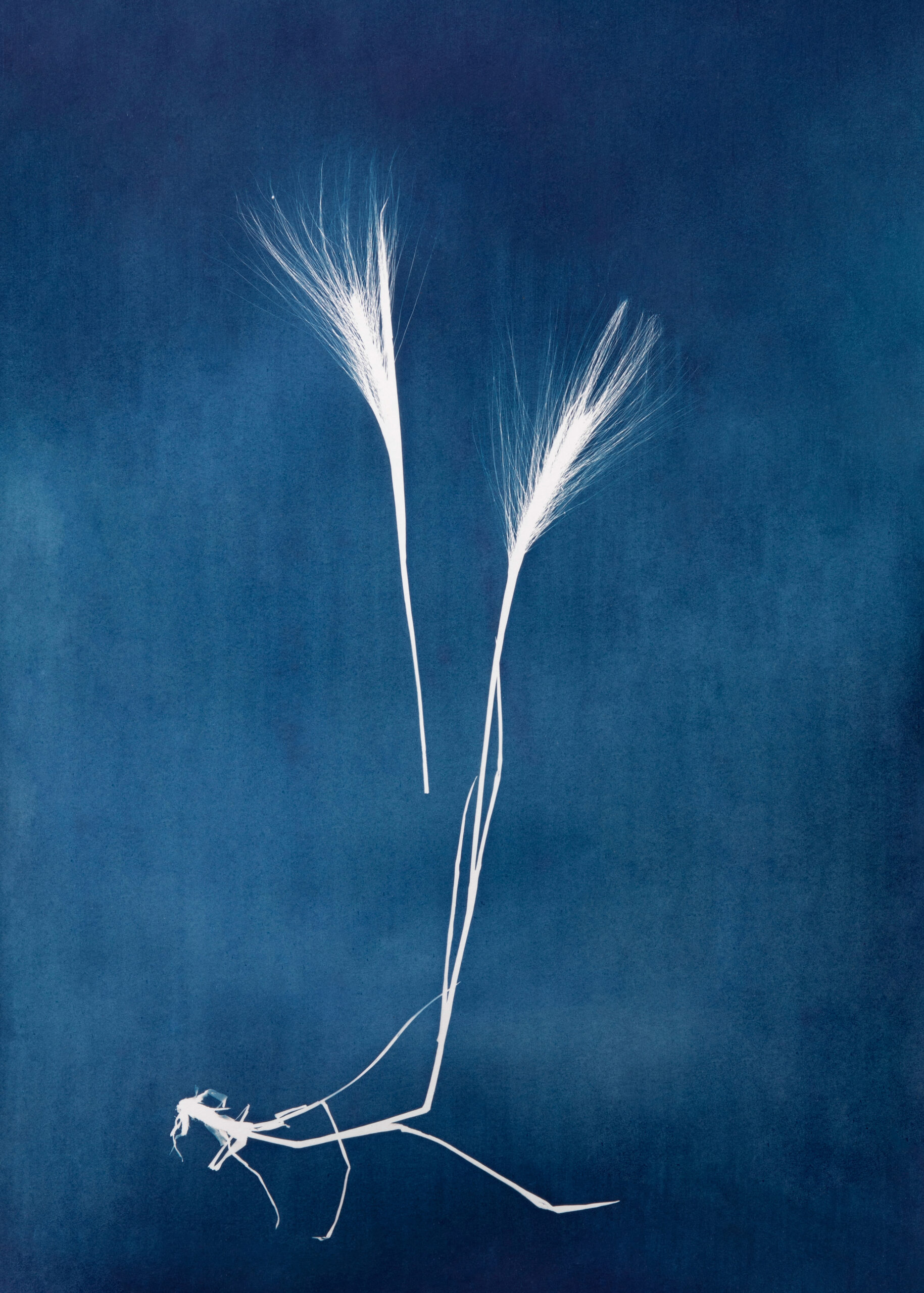

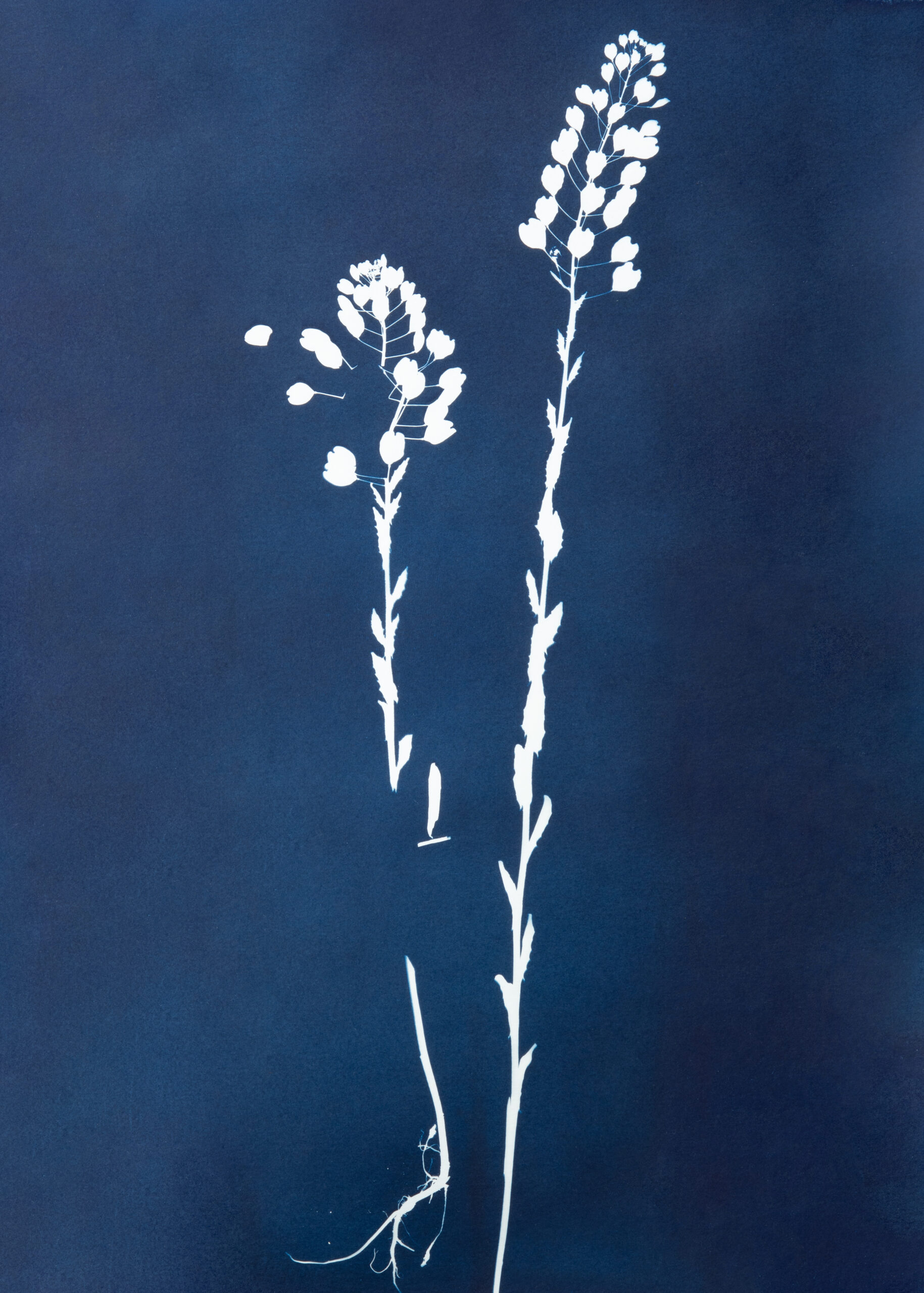

Displaced Garden is the latest work of Montréal-based Iranian artist Anahita Norouzi, exploring the legacies of botanical exploration, plant-collecting and documentation inherited from colonial scientific expeditions. Taking the form of a photographic book containing 18 cyanotype impressions of plant specimens, the project results from a collaboration between the artist and eight refugees from the Middle East and Africa. The participants were invited to ask their families in their home country to mail the artist dried plants native to their land, but categorized as “foreign” and “invasive” in Canada. These “invasive” species are indeed amongst the most common in Canada, bursting through asphalt and thriving in alleys and roadsides.

The series portrays each specimen individually and in the state in which it arrived by mail, showing signs of damage and deterioration caused by transportation. Featured alongside the blueprints are postage stamps and postcards attesting to the species’ cross-continental journey, and short texts referring to the histories of war and colonialism that have shaped the countries from which the samples were collected.

Through this work, Norouzi comments on the processes of botanical extraction from colonies around the globe that drove the expansion of Western scientific knowledge and territorial conquest, while at the same time reversing the roles and subverting the colonial gaze. Here, immigrants from once-colonized countries are the ones collecting and transferring plants from their native land to the West. Norouzi chooses to reappropriate methods of botanical photography in order to engage in a decolonial reading of its history.

(Introduction by Julia Eilers Smith)

The Morice Line was a defensive line that went into effect in September 1957 during the Algerian War of Independence, fought between France and the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN). The line was 460 km long and sealed off Algeria’s eastern and western borders to prevent FLN guerrillas from entering the colony from Tunisia and Morocco. The centre of the line was an electric fence 2.5 m high that carried a 5,000-volt charge for its entire length. On each side of the fence there was a minefield, heavily mined by the French—with a density of one landmine per metre—for a total number of 11,064,180 mines. The use of alarms, radars, checkpoints and anti-personnel landmines made the Morice Line impenetrable.

Following the end of the war in1962, extensive efforts were made by the new Algerian authorities to clear and dismantle the Morice Line. Decades after the conflict came to an end, the Morice Line continued to cause casualties among local Algerian populations. It is unclear how many civilians have been killed or wounded by landmines. According to the Algerian newspaper El Acil, there have been more than 40,000 victims of mines since the country’s independence. In October 2007, French Army General Jean-Louis Georgelin finally handed over maps that detailed the extent of the contamination and the exact locations of the mines. The French government had been in possession of the maps since the ceasefire in 1962.

Algeria eventually joined the Ottawa Treaty, which bans the use of landmines, and agreed to the obligations of the Convention. In 2017, Algeria finally announced that after decades of work, it had fulfilled its mine clearance obligation under the treaty.

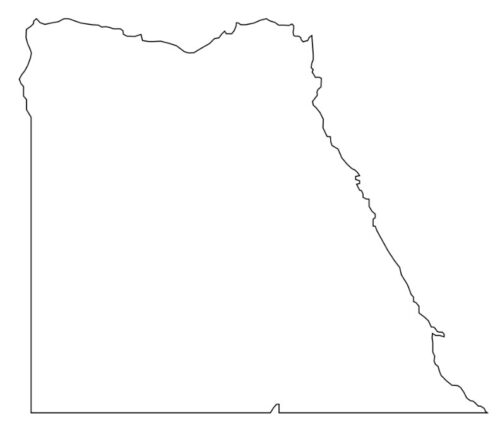

In January 1899, the UK and Egypt (a British protectorate at the time) signed an agreement and established the shared dominion of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, defining “Sudan” as the “territories south of the 22nd parallel of latitude.”

In November 1902, the UK drew a separate “administrative boundary,” intended to reflect the actual use of the land by the tribes in the region. Bir Tawil, a grazing land used by the Ababda tribe located above the 22nd parallel, was placed under Egyptian administration. Similarly, the Hala’ib Triangle to the northeast was placed under the British governor of Sudan, because its inhabitants were culturally closer to Khartoum. The discrepancy between the straight political boundary established in 1899 and the irregular administrative boundary established in 1902 has resulted in Bir Tawil currently being claimed by neither country, and the Hala’ib Triangle being claimed by both.

The Hala’ib Triangle is an area measuring 20,580 km2 located on the coast of the Red Sea. With the independence of Sudan declared in1956, both Egypt and Sudan claimed sovereignty over the area. The area has been considered a part of Sudan’s Red Sea state, and was included in local elections until the late 1980s.

Although both countries continued to lay claim to the land, joint control of the area remained in effect until1992, after the unsuccessful assassination attempt against Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak during his visit to Addis Ababa. Egypt accused Sudan of complicity and strengthened its control over the Hala’ib Triangle, expelling the Sudanese police and other officials. The Egyptian government converted the village of Halayeb into a city and launched various civilian projects, which have been under construction ever since. In 2010, Sudanese president Omar Al-Bashir claimed that despite Egypt’s de facto control of the Triangle, the area still rightfully belonged to Sudan.

In 2014, a 38-year-old farmer from Virginia named Jeremiah Heaton laid claim to the Bir Tawil land, to make his daughter a princess. The United Nations did not recognize Heaton as the legitimate ruler of Bir Tawil, as only individuals who have lived on a territory for years can assert sovereignty over that land.

The Congo Pedicle—meaning little foot—is the southeast salient of the Congolese territory that cuts deep into neighbouring Zambia and divides it into two lobes. It is an example of the arbitrary boundaries imposed by European powers on Africa, without considering pre-existing political and tribal territories.

After a decade of dispute between the British South Africa Company of Katanga, from the north, and the Congo Free State ruled by King Leopold II of Belgium, from the southwest, Zambia’s formal northern frontier boundary was legally signed in the Anglo-Belgian Treaty of 1894. However, the Lake Tanganyika Cape, mentioned in the treaty and described as a reference point for the division of the land, planted the seeds of subsequent border disputes. British maps showed the boundary meeting at Cape Chitankwa, while Belgian maps showed the meeting point far south of Cape Chitankwa, thereby cutting deep into assumed Northern Zambia territory.

The Congo Pedicle has been a major hindrance to Zambian development since its independence in 1962. It cleaves the country into two lobes of roughly equal size and cuts off the eastern and western parts of the Northern Province from the country’s industrial and commercial hub, the Copperbelt. Transportation is another major problem. Traveling from northeastern to central Zambia is not too difficult if one crosses the Pedicle, but getting around it is arduous, with the Bangweulu wetlands standing in the way. The pedicle itself has also remained isolated from the rest of modern-day Congo and is consequently underdeveloped, except where mining occurs, for which the pedicle receives no share.

The Moroccan Western Sahara Wall is a 2,700-km-long structure, running through Western Sahara and the southwestern portion of Morocco. It separates the Moroccan-occupied areas (the Southern provinces) on the west from the Polisario-controlled areas (Free Zone, nominally called the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic) on the east.

The fortifications consist of sand and stone walls or berms about 3 metres tall, with bunkers, barbed wire, electric fences and an estimated seven million land mines. The barrier mine belt that runs along the structure is thought to be the longest continuous minefield in the world. Military bases, artillery posts and airfields closely monitor the Moroccan-controlled side of the wall at regular intervals, and radar masts and other electronic surveillance equipment scan the areas in front of it.

Morocco gained independence from France in 1956. Inspired by the idea of creating a Greater Morocco, the government claimed all of Spanish Sahara as a Moroccan land. Saharawi nationalists had meanwhile formed the Polisario Front, seeking independence for the Spanish Sahara, and began a guerrilla campaign. An International Court of Justice ruling on the matter in October 1975 rejected the Moroccan claim to the Spanish Sahara, and stated that the Saharawi people should be allowed to determine their own future. Morocco thereafter sought to settle the matter with military force—in November 1975, it conducted the “Green March,” as thousands of soldiers forcibly crossed the Morocco-Spanish Sahara border. The Polisario troops that had declared a Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic based on the boundaries of Spanish Sahara thus started waging a long war against Morocco.

Morocco and the Polisario Front signed a ceasefire agreement in 1991, ending the war, with Morocco retaining control of areas west of the wall, and the Polisario controlling those located east. However, to this day, the dispute over the borders has remained unresolved.

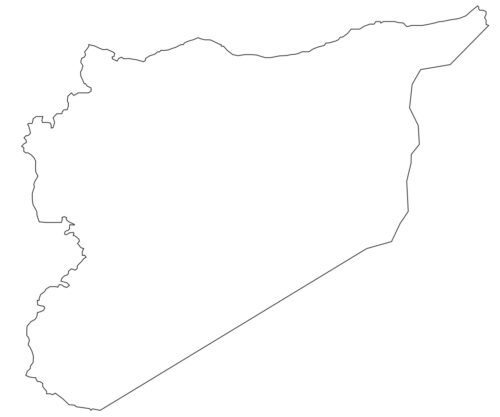

Between 1920 and1923, France and Britain signed a series of agreements known as the Paulet-Newcombe Agreement, which created the modern Jordan-Syria and Iraq-Syria borders. It was an amendment to what had been designated as the zone of French influence in the Sykes-Picot Agreement.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement was a secret 1916 treaty between Britain and France that defined the border of the French Mandate for Syria and Lebanon, and their mutually agreed-upon spheres of control in an eventual partition of the Ottoman Empire. The agreement allocated to Britain control over what is known today as southern Israel and Palestine, Jordan and Iraq, and an additional small area that included the port of Haifa to allow access to the Mediterranean. France was granted control over southeastern Turkey, northern Iraq, Syria and Lebanon. The logic behind this division was to award the roads to Syria and the water resources to Palestine.

Although the European powers withdrew after WWII, the “artificial” borders that they created remained. These borders negated the UK’s conflicting promise of creating a national Arab homeland in the area of Greater Syria in exchange for the Arabs’ support for the British against the Ottoman Empire. Each country expected the land to remain in their hands, which seems to be what the British had promised them.

The latter also broke their promise to the Kurds to make provision for an independent Kurdish state. The 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which officially settled the conflict between the Ottoman Empire and the Allied forces, made no such provision and left the Kurds with minority status, scattered throughout southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northern Syria. This has led directly to numerous genocides and rebellions, along with armed conflicts in Turkish, Iranian, Syrian, and Iraqi Kurdistan until today.

On August 6, 1914, the French and British invaded the German protectorate of Togoland in West Africa and began the West African campaign for WWI. German colonial forces withdrew from the capital, Lomé, and the coastal province, to fight and delay actions on their way to Kamina, where the Kamina wireless transmitter linked the government in Berlin to Togoland, the Atlantic, and South America. The German defenders delayed the invaders for several days, and finally surrendered the colony on August 26. They demolished all the radio towers and destroyed the electrical equipment before abandoning Kamina.

Two years later, in 1916, the victors partitioned Togoland into British Togoland and French Togoland, which cut through administrative divisions and civilian boundaries. The French acquisition consisted of roughly 60% of the colony, including the entire coastline. The British received the smaller, less populated and less developed portion of Togoland to the west.

In May 1956, as part of the decolonization of Africa, a referendum was organized in British Togoland to determine the future of the territory. The referendum was held under UN supervision and gave two alternatives to the people: to unite with the neighbouring country of Ghana or to continue to be known as a Trust Territory until neighbouring French Togoland had decided on its future. Independence was not listed as an option. The Togolese Ewe, a dominant ethnic group native to Togoland, preferred amalgamation with French Togoland. However, the result was reported to be 58% in favour of integration with Ghana, and 55% for unification with French Togoland. Despite concerns over the lawfulness of the referendum, the area was united with Ghana as an administrative region.

Nowadays, the result of the transfer of Togoland to Ghana is that many Togolese people keep one foot on either side of the border, living in Ghana by night and working in Lomé by day.

After Tunisia gained independence in1956, France remained in control of the city of Bizerte and its naval base, a strategic port on the Mediterranean, which played an important part in French operations during the Algerian War.

In 1961, Tunisian forces blockaded the naval base in hopes of forcing France to evacuate its last holdings in the country. France had promised to negotiate the future of the base, but had until then refused to remove it. Tunisia was further infuriated upon learning that France planned to expand the airbase. After Tunisia warned France against any violations of Tunisian air space, the French defiantly sent a helicopter. Tunisian troops responded by firing warning shots. In response, 800 French paratroopers were sent in as a show of force. When the transport planes with the paratroopers landed on the airfield, Tunisian troops engaged them with targeted machine gunfire. In response, French jets supported by troops thoroughly attacked the Tunisian roadblocks, destroying them completely.

The following day, the French launched a full-scale invasion of Bizerte. Tanks and paratroopers penetrated into the city from the south, while marines stormed the harbour from landing craft. Tunisian soldiers hastily organized civilian volunteers and engaged in heavy street fighting with the French, but were forced back by vastly superior French forces. The French overran the city on July 23, 1961, and left some 630 Tunisians dead.

Tunisia appealed to the United Nations, but the UN was unable to carry out any sort of substantial action against the French. The French troops occupied the city until the fall, but did not abandon its naval base until late 1963.

All artwork and images © Anahita Norouzi

For more on Anahita Norouzi’s work, please visit her website.