Annie (Kishkwanakwad) Smith St-George is a well-recognized Algonquin Elder, born and raised on the Kitigan-Zibi reserve near Maniwaki, Quebec. She was the founder of Kumik, the Elders Lodge (Indian and Northern Affairs Canada) established in the early 1990s following the Oka crisis. Elders came from across Canada to share their teachings and knowledge, and to help Annie who, at the time, was recovering from the loss of her son. Subsequently, she founded WAGE, a health centre for the integration of Aboriginal knowledge with medical science. Annie and her husband, André-Robert St-Georges, have been featured in the National film Board (NFB) film Kwekanamad/The Winds are Changing/Les vents tournent.

The Serai interview was conducted in a spirit of observation and active listening rather than questioning. Annie’s husband, André-Robert, also participated in the conversation. The narrative below is based on their words.

Annie Smith St-Georges met me at her home in Gatineau, Quebec. “Women and Health,” she mused, “makes me think of my own condition.” “I am going through a change in life; my daughter-in-law is going to have a baby. I am thinking of how our health impacts on our lives…. Now, shoot the questions you have…. Meet Tigar, our cockatoo. He has a blanket over his cage because I am allergic to something in the new seeds that we brought. But perhaps, we will let him out. He likes to be outside, and he likes to eat what I eat. He does not talk, but he whistles…..Now, what kind of questions do you have?”

Annie had a way about her that made me think that I would need a lot more time than I had set aside for this interview to learn all that she had to teach me. I would have to follow in her steps, just like she did as a child, and wait for her to pick medicinal plants hidden beneath the barks of trees and under bushes, just as her mothers and grandmothers had done in the past.

“An elder can be very different from an elderly person,” she pointed out. “Someone at the age of thirty can be an elder, and others at the age of 65 might not necessarily be so.”

“But, everyone is a teacher. Look at children! They are our best negotiators! We all have something to teach, and in the same way, we all learn from others.

“I was raised as a trapper. My mother was a farmer’s daughter, and everything that she grew and cooked was organic. My father was 15 or 16 years older than my mother. He hunted game, and brought home moose meat. Turnips and other vegetables were preserved underground since we had no electricity. Some vegetables were waxed with paraffin. Potatoes were kept in a dry box in the ground. Dad cut ice from the lake in the winter and wrapped it with sawdust. This provided us with a supply of ice for our coolers. Mom tried to give us the best from nature, but we didn’t have much of anything more than that. The only fancy food I remember was Jello – I think it came out in 1955. I still have one of the original cartons of jello.

“Mom made her own bread on a wood stove. I was the only sister of two brothers. Ours was not a big family. Mom and Dad worked together. They were both good at crafts. Dad cooked breakfast and cleaned the house just as Mother did. Mom hunted just as I did. We used to trap muskrat, beaver for the fur trade. We prepared their skins. For the most part, we used traditional medicines. There were no phone lines. When we were sick, there was a nurse in the community, but she never seemed to have time. Neighbours helped. My brother used to have seizures, and the medicine woman from the neighbourhood would come and treat him. He would recover. It was called “pinago” which means “seizure” in Algonquin. I did not stay in the room, but I know that she used a lot of salt. The seizures went away. In fact, he survived until last year. My grandfather lived until he was 97. My father died at the age of 90. My mother died when I was 34. As a child, I did not eat much. I am still picky – as you can see, I don’t like to eat the crust on my bread.

“I had to leave my community because I lost my status at the age of 18/19 after I married my husband who is Métis. I was not allowed to inherit from my parents, nor was I allowed to live in the community. This lasted until 1985, when I was reinstated following Bill C31. We have been married now for 41 years. You cannot choose your marriage partner. In fact, love happens, and when it does, you have no choice! André-Robert has adopted more of my culture than I have. He has a circular way of thinking.

“Her first gift to me,” said André-Robert, “was a baby raccoon. He died because he got out of the house. He liked to lick the salt from the asphalt, and liked to lie down on it to warm itself. He got run over. Raccoons clean and wash their food before eating – at least the raccoons in the countryside do that. The ones in the city are vicious. Groundhogs are very intelligent. Like dogs, they can be trained to roll up, and to beg for food.”

“But we had our differences,” said Annie. “For example, he felt that our children should be in bed by 7:30 p.m. I believed in allowing them more flexibility especially during the pre-school period. We had arguments, but I had my way. It is the mother’s role to pass on traditions and culture to her family. The children went to bed whenever they wanted to – just like it was at home.

“However, respect was a very strong priority for me and my children. Respect means many different things: not to cause damage or hurt, and not to steal or to take what is not yours. Respect is almost like having one word for all the Ten Commandments. A lot of stuff is built around respect. There is respect for one’s body, to prepare it for carrying babies, and to make sure that diseases are not passed on to one’s children. Grandmother was strict on that. She required us to abstain from sex until we were married. This is, of course, a personal choice. Does that apply to boys? Yes, to a certain extent, but there are less restrictions on boys because of the patriarchal system within Christianity that had a huge impact on us.

“Mom was Catholic. Dad was traditional Algonquin Mohawk. He had a lot of respect for nature and the natural way. He told me that we would not exist without trees and animals. As a hunter, Dad took only what he needed. Nothing from the animal was wasted. Out of moose hide, we made leather goods such as moccasins, drums and other products. Antlers were used to make tools. Parts of bone were used to make games, jewellery and instruments. Meat that we could not consume was fed to dogs, and the insides of animals were used to hunt again. If an animal was not edible, it was buried.

“We believe that we should take only what we need from Mother Nature, and do so with respect for all that she has to offer us. For example, before we take anything away from a tree, such as its bark or a branch, we give an offering of tobacco as a sign of our appreciation and gratitude. When we do need to take down a tree, we do not clear cut, and we replace it with another of the same kind so that pine and spruce are grown where they grow best, and are not replaced by eucalyptus or bamboo. Most people today are not as sensitive to local habitat and believe in harsh clear cutting that causes a serious disturbance in the natural order of things.

“Dad would try not to hunt down a young female animal because that would prevent further reproduction. If there were young ones that were orphaned, he would look after them. I was raised with young bears, skunks, groundhogs, ducks, chickens, and porcupines. Mom cared for them, and healed them. We released them when they were releasable, or we sent them away where they could be looked after well. We had a pet bear cub for 9 years. He was called “Cocons” which means “little bear” in Algonquin. He weighed 500 lb. Dad once brought home a lynx. Didn’t know how he did it. We kept it in a cage and released it when it was healed. All of us – the animals, the children and our parents – lived at the same location. No, there were no cameras, and we had very few pictures. I have one of the bear, but it is in a box in the basement.

“We don’t make fire just for fun. According to Algonquin tradition, it is most important not to interfere with the natural order of things. For example, we believe that it is better not to touch dead wood which, when left alone, can become even more valuable than trees. It is better instead to break the fresh branch off a tree that can be cut without causing too much harm.

“Also, forest fires are there by natural law, since without them, there would be no berries and no new vegetation. In fact, the most dangerous fires are often caused by careless people who unthinkingly leave pieces of glass or mirrors in the forest.

“In fact, we believe that on this planet, the trees, animals, fish, plants and human beings are all equal and related to one another. Our teachings tell us to look at everything as one whole very much like what the earth, water, mountains, trees and green vegetation look like at 120 miles from above. At times, people are afraid of others who seem more powerful because of their important positions or titles. However, this does not mean that any one person is higher or superior. In the Creator’s eyes, we are equal, and all part of Mother Earth.

“We also believe that the food we eat should be the kind that is in tune with nature, and that grows well in our climate and environment. Each location has its own special nutrition, all according to its unique natural soil and conditions. We believe that the food grown locally and naturally is the best kind of food for us, and that if we have blueberries, our bodies will need them, just as if we have fish, it will be good for us. ”

“Women perform water ceremonies, and are caretakers of water because we bear children in water. The full moon also has to do with water in the women’s circle. As for men, they keep the fire going. Fire is very important for three main reasons: it keeps us warm, prepares our food, and helps us perform ceremonies. We respect this through our offerings. Pieces of food are placed on a plate, and we undertake the Smudge. During these feasts, and while making the offering of food and tobacco, we thank the Creator, and acknowledge our ancestors. After that, we give it all back to Mother Earth, or feed the fire.

“In the traditional Algonquin way, young girls followed grandmothers for picking medicine. My great grandmother was a Medicine Woman. However, she had to take it underground because she could have been punished or jailed for practicing traditional medicine. Not all communities were the same, and many changed to adopt more Christian ways. Many were afraid to practice in traditional ways since these were considered to be evil. However, traditional ways that teach the values of respect, kindness and honesty, are simple and straightforward, not evil. It is only recently, that this has been accepted, and people are being encouraged to go back to their roots. Elders are being invited to share their knowledge, and people are becoming more open to incorporating our beliefs and systems.

“The Medicine Wheel is, in fact, not just a Medicine Wheel. It is a way of life. It provides a connection with all aspects of our health – the physical, the mental (intellectual), the emotional and the spiritual. It embodies how we heal ourselves and a way in which to look at all parts as one complete whole. Every cell in one’s body is a replica of what is out there in the atmosphere. Every cell has a memory. At conception, when the cell subdivides, it captures billions of bits of information that go back to many past generations. Knowledge is also sometimes transmitted by cells, and Aboriginal healers have retained their ability to trigger the memory of cells. In this manner, we hold hundreds of billions of people and creatures in ourselves. We believe that one third of our weight is from other species. Aboriginal women healers knew that. By their touch they were able to trigger a process to transmit the right kind of energy through memory. I share these teachings a few times a year with the Medical Faculty at the University of Ottawa.

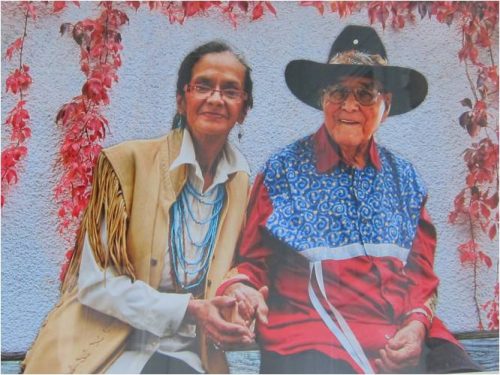

Our conversation drifted to Annie’s uncle, Grandfather William Commanda. Annie and André-Robert brought out a framed Carol Noël photograph taken on Aboriginal Awareness Day just before William Commanda’s death in August 2011. An Algonquin Elder and spiritual leader, William Commanda (1913-2011) served as Band Chief, and worked as a trapper and woodsman. He was a skilled craftsman who excelled at constructing birch bark canoes. “He was Keeper of several Algonquin wampum shell belts which held records of prophecies, history, treaties and agreements. In 2008 he received the Order of Canada.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Commanda

In appreciation of the time spent with Annie Smith and André-Robert St-Georges.

Gatineau (QC) May 25, 2013