Little Burgundy Piano

In his room by St. Antoine, in a stone house

Steep Wade sits on the edge of his bed and listens to the train,

hears the grumble of the wheels, the squeal of the brakes

while in his hands and fingers the ghosts of Tin Pan Alley tunes sleep.

The curtains, diaphanous but stained a faint brown,

filter sunlight from the street. The ashtray

fills with butts from the cigarettes he smokes, one after the other

in patient meditation, as a song sails through his soul.

It does not do anymore to hang out at “the corner,”

at Café St. Michel, Chez Parée. The curious

crowds come more for each other than the music.

Here he can sit and listen to the sketches of spontaneous birds

outside the window, and watch the harmonies

played by the sun through the clouds and feel the rhythms

of the streetcars and buses that remind him of playing to Bird’s horn

when he came through town looking for the one

who could feed him chords like no one else,

the one who has decided

he’s had enough of life

and contemplates other possibilities.

Boogie Gaudet

“I don’t know how he does it,” says the barmaid

as the saxophonist lights up another one.

“He smokes one pack a day, down

from two packs.” These are facts.

Another fact is he’s a 74-year-old

saxophone player who can swing his tenor

like a seasoned woodsman does an ax,

chopping logs in stacks.

Or he cradles it like a dancer dropping a partner

in the amorous curl of a dance.

He pivots on the brink of a melody

that comes to him as he plays.

He stops, listens to what others have to say,

piano, bass, and casually flips another cigarette

into his mouth when the drummer starts his solo.

Tamer of the tenor since he was ten, he sloops back to his sax,

lifts nuggets from Newk, wisdom from Webster,

spiels the language inside-out and backwards, can

babble it in Pig Latin, thinking

on his feet as if music were dance

and dance all you need to know.

Slip-knotted, double-jointed,

smokescreen dazzle,

he’s back with a clear statement,

his horn-rimmed glasses slipping down his nose.

“We’re going to do one last one

then we’ll head to the bar for a transfusion.”

That’s where I approach him, yellow-fingered,

impish before a pint. I introduce my friend.

“He also plays tenor,” I say.

“My sympathies,” he says.

“He speaks French and Spanish,” I say

and in Spanish he curses the saxophone he’s known for 60 years

like old men sometimes speak of wives

who’ve made them know love’s give and take

but whose lives are deeper

than those of men who choose to sleep alone.

Dropping Notes

Oscar Peterson’s piano playing was highly glossed and brilliant.

He was the Maharaja of the keyboard, they said.

Technique sparkled like ceremonial regalia

as he rolled out the royal carpet of the American Songbook and the blues.

Music was in his heart and soul

as smooth as a silk suit and as flamboyant as

a specked tie, and the flourish of song

rushing through a room

washing away the dirt from our ears.

When he started dropping notes late in his career

his wife got suspicious and so did his peers

and a doctor found he’d had a stroke,

which explained things.

I’ve always dropped notes. Like most

mortal musicians, it’s part of my sound.

When I play, the glitches leave something out,

the missed note, dropped

into eternal silence, but for Oscar to tumble

to such depths, it took a stroke.

He said at a press conference at the Ritz in Montréal

that musicians are master mathematicians

and dared anyone to defy it.

Everything the hands and fingers and breath translate

into song, he seemed to suggest, is precisely placed.

After they rolled him into the auditorium the night

a university concert hall in Montréal was named

in his honour, he struggled over to the piano bench,

his left hand flopped simplistically like a lesser pianist’s

while his right hand did its usual magic.

In his shadow I ply my plectrum

and push the strings into chords

and lines of song that are mere wisps

of the possible that Oscar knew so deeply,

and though his hands have failed

we still hear the silence he has left us as a reminder

of the glitch that eventually gets us all.

Respect

Outside the music practice room door

I wait to speak to the man inside

teaching a student the finer points

of John Coltrane’s “Impressions.”

I can’t tell who is student, who is teacher from the sound.

Both fluid, smooth and round trumpets, air through tubes

singing in the sweet spring academic air.

A backing track

plays the piano chords, bass lines and drum accompaniment.

Someone improvises a simple variation

and then an embellishment of the simple original melody.

A pause. The student repeats the teacher’s phrase.

Another pause. Then more lines, more repetition and soon

you can’t tell who is playing what.

The tone is pure, vibrato-less, dignified and poised,

though only three notes are used in motivic fashion,

inverted, retrograde, another note interpolated,

ultra-polated, infra-polated, ultra-infrapolated

to the whim of the imagination of the player

here restricted by the simplest of forms.

The track hovers for a few seconds in a fermata

and then there is silence. Seconds later,

cases snap shut. Voices mumble something, then

the door springs open and Professor Charles Ellison emerges,

black slick trumpet case in hand.

I greet him. We are to sit for an interview

on the jazz scene in Montréal. I’m writing

an article for Downbeat, an overview

of Montréal as a jazz town, and Ellison

is part of it, helped define it as an educator.

I tell him the session sounded interesting and that

I couldn’t tell the student from the teacher.

He looks at me puzzled, maybe insulted, annoyed.

I say the playing was beautiful.

He tells me that students don’t know

how to play the blues.

He was teaching how to play the blues

in a meaningful way

even if it’s not over blues changes, but two chords

like Coltrane’s tune

based on Miles Davis’s “So What.”

He tells me something like “people play the blues like

they wear expensive ragged jeans, rather

than proper clothes. I think the blues are like that.

You wouldn’t wear ragged jeans if you were poor

unless you had to, so why

play the blues that way? The blues

can be dignified and should be treated with respect.”

He then tells me about how people do not give seats up to the elderly on buses.

“I’ll come up to them and tell them to do so, if I see that,” he says.

“Respect!”

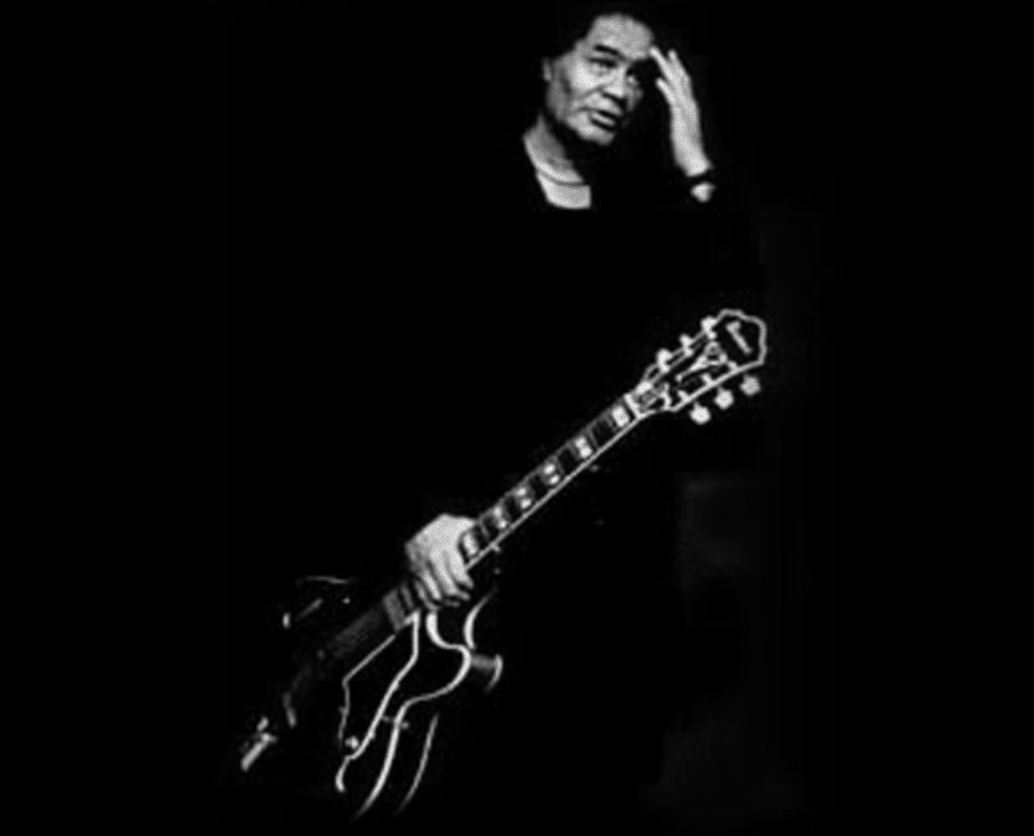

Search for God

I remember staring at

Sonny Greenwich’s hands

as he played on the stage

of l’Air du Temps

in 1983. His right hand

held a pick between

thumb and index

and stroked

ecstatic notes

out of the guitar

that swelled with

the cymbal splashes

and bass tremolos,

as his left hand, three-fingered,

stepped across the frets

like a high-tension wire lineman in a rainstorm.

When he played

chords, steadily

stacking sonic shapes

like toddlers’ building

blocks in an unheretofore

imagined manner, he used

all four fingers, his thumb

wrapped around the neck.

In the creative brain,

what goes on? Decisions

to make on the fly and once

you’ve made them there’s

no stepping back.

I remember, too, his big frizzy hair,

his serious face, his stare at me,

because I was back the next night

watching him again, listening for

the soul of every note

in which Sonny said was

his search for God.

Three Toes Short

Billy Barwick played the meanest hi-hat in town

even though he lost three toes from his left foot

when he was nine, some say in a mowing accident,

some in a run-in with a steamroller.

“Our dream was to go to New York,”

Billy said. But he never left Montréal.

Played instead for dancers and mobsters

in the good old mafia days though they smashed up his drums

one time in a late-night shoot-em-up raid.

At the Seville Theatre in 1945 playing hooky

with his buddy Doug Rollins, he heard Satchmo and Count Basie,

ogled the dancers and wanted to be with them,

him three toes short. Long on attitude and percolating

with rhythm he picked up sticks instead,

taught himself to swing on skins.

But swinging wasn’t enough. The needle

made him one of those nodding junkie cats

who floundered on the rocks of jazz hipster lore

losing the battle between this world and the dream world

realer than any jazz riff could take him to.

Billy died in 2006 of stomach cancer,

had lost a lung to tuberculosis,

had been in and out of drug rehabilitation

and had also become nearly blind.

After his death, a fellow musician said,

“When he was straight, he was a good drummer.”

In 1990, for a gig with the Dawson Blue Devils,

his old buddy Doug Rollins’ band,

we loaded his kit into my Honda. He looked

like Chet Baker. Same

slicked back hair. Same

1980s large-framed glasses. Same

sunken cheekbones. Same

furrowed junkie face, hankering

for a cigarette, though he was trying to quit.

He liked my mustard-yellow B Flat zoot-suit jacket.

It reminded him of old times, and we shared a smoke.

And later with Doug blowing hip, Billy danced

across the drums, and made that high

hat sing, him three toes short.